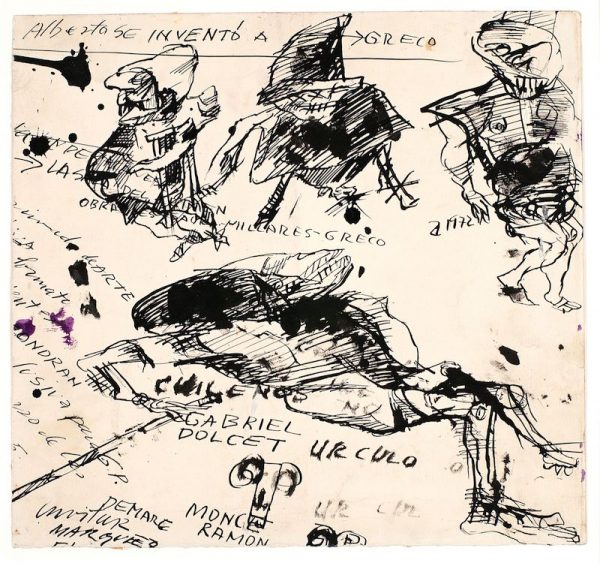

“The artist will not teach us to see with his picture but with his finger,” wrote Argentine artist Alberto Greco in 1962. “He will teach us to see again what is happening in the streets.” Three years later, in Barcelona, Spain, Greco chose to perform a final gesture, writing “This is my best work,” on a wall as he floated into the mystery, his life intentionally ended by barbituates at age 34.

Greco’s last piece of art was clearly the most radical statement one could make in response to political, social, and cultural repression, but artists throughout Latin America engaged in revolutionary DIY art as their own particular expressions of the conceptual art-think zooming around the continents in the kaleido-cray-scape of the 1960s. From the Page to the Street: Latin American Conceptualism, at UT Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art, presents a survey of mail art, photography, video, artists’ books and periodicals, concrete poetics, and ideas for art actions, created from the early ‘60s to the 1980s. While the work is more politically overt than the more “formal innovation” of conceptualists elsewhere, Blanton curator Julia Detchon notes that the Blanton show aims “to track a history of radical experimentation happening at the object level. The art is conceptual insofar as it redefines the relationship between artist and viewer from a didactic one to a collaborative one.” And Latin American artists, so many of whom were responding to the dire circumstances of living under dictatorial regimes, nonetheless shared those characteristics with their North American and European peers.

Alberto Greco, Alberto se inventó a Greco [Alberto Discovers Greco], between 1963 and 1965. Ink on ivory paper 12 1/2 x 13 5/16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Barbara Duncan, 1974

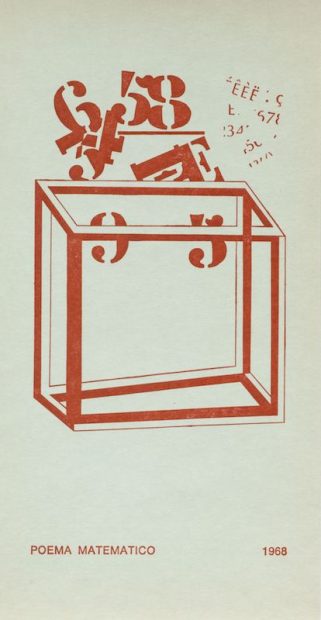

Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Poema matemático [Mathematical Poem], 1968. Rubber stamp with letterpress on green cardstock, 9 5/16 in x 4 13/16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of the artist, 1995

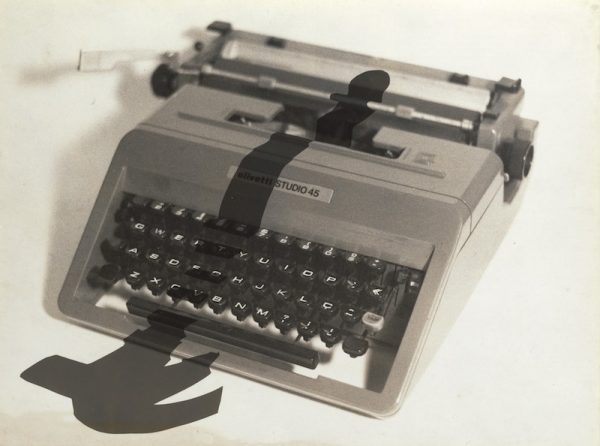

Regina Silveira, Enigma 3, 1983 (detail). Postcard. 4 15/16 x 6 5/16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Jacqueline Barnitz, 2017

Brazilian conceptualist Regina Silveira (b. 1939) is represented by four postcard photomontages, Enigma 1 through Enigma 4, depicting shadows laid across items: a saw shadow over luggage, hammer over typewriter, comb over a cooking pot, and a fork shadow over a dial phone. “I have always been interested in the mental and temporal relationship that shadows stain with their present or absent references,” the artist explains. “In short, this is a vast field for poetic operations… .” As Detchon notes, the “incongruous pairings are alternately menacing and harmless.”

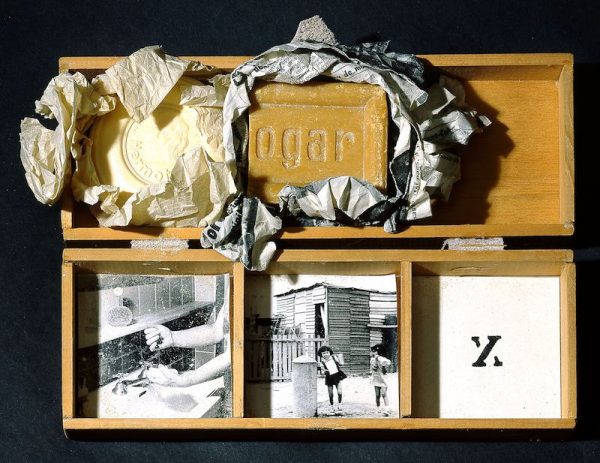

Alfredo Portillos, Caja con jabones para distintas clases sociales [Box with bars of soap for different social classes], 1974. Artist’s wooden box with leather hinges, two bars of soap in tissue and newspaper, two photographs. 2 x 10 1/4 x 3 11/16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

Cildo Meireles, Zero cruzeiro, 1974-1978. Photo lithograph. 2 13/16 x 6 1/8 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Paulo Figueiredo, 1982

![Anna Bella Geiger O pão nosso de cada dia [Our Daily Bread], 1978 Brown paper bag containing series of six black and white postcards 16 15/16 x 5 1/2 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Shifra M. Goldman, 1999](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Geiger-600x507.jpg?x88956)

Anna Bella Geiger, O pão nosso de cada dia [Our Daily Bread], 1978. Brown paper bag containing series of six black and white postcards. 16 15/16 x 5 1/2 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Shifra M. Goldman, 1999

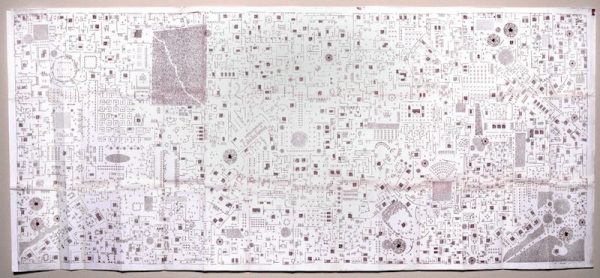

León Ferrari, Bairro, 1980 Heliographic print. 43 x 97 9/16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of the artist, 2007

Persuaded by his artist father not to follow such an uncertain career path, Buenos Aires native León Ferrari (1920-2013) trained as an engineer. Life under a junta, however, radicalized Ferrari and inspired him to resort to making art. With fellow Argentine Vigo he shared a sad kinship; after Ferrari was exiled to Brazil, his dissident son Ariel “disappeared.” In 2004, the artist famously pissed off the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, who later became the current Pope. His piece at the Blanton, Bairro [Neighborhood], is a large heliograph that deploys Letraset icons with rubber stamps and drawn material. For one of Ferrari’s “editions of infinity” that he mailed to friends, the depicted ‘hood is one of topsy-turvy, chaotic order and contradictions befitting the modern scene.

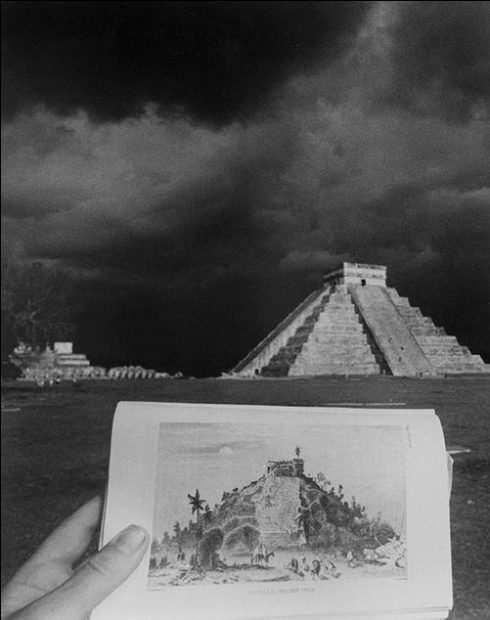

Leandro Katz, El Castillo (Chichén Itzá), 1985. Gelatin silver print. 20 x 16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase through the generosity of the Charina Endowment Fund, 2017

Three gelatin silver photographic prints from The Catherwood Series by Argentine Leandro Katz (b. 1938) offer a wry commentary on the colonial consumption of Mexican antiquity by the famous “American Traveler” John L. Stephens and an English artist-architect-explorer named Frederick Catherwood. The pair “discovered” the ruins of “lost” Mayan cities in the 19th century, and their 1841 book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, is often regarded as a “watershed” achievement in Maya studies. For his 1980s-90s in-their-footsteps performance, Katz visited sites that Catherwood documented by drawing with the aid of a camera lucida. Holding a copy of Incidents out before him, open to the specific page with Catherwood’s drawing of the archeological site being visited, Katz “rediscovered” the preserved ruins. Shown here, The Castle, Chichén Itzá [El Castillo, Chichén Itzá] contrasts the site in its unexcavated state with its more recent trekker-ready dynamism. Adding a touch of levity, Katz’ camera also captures his thumb and finger holding the open Incidents.

Sent to the United States by her parents after the Cuban Revolution, the work of Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) has often been overshadowed by the terribly sad and tragic story of her death. For the past decade or so, however, more attention has been paid to her powerful, elemental — and often lyrical — gestures, actions, and images of her body and earth art. Even sectors of the artworld that just can’t help themselves from blathering about the evolving dollar value of Mendieta’s “mesmerizing” pieces note that a “cult” now swirls around her memory and work.

![Ana Mendieta Itiba Cahubaba II [Old Mother Blood], from the Rupestrian Sculptures Series 1981/1983 Photo-etching on chine collé](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Mendieta-458x620.jpg?x88956)

Ana Mendieta, Itiba Cahubaba II [Old Mother Blood],1981/1983. Photo-etching on chine collé. From the Rupestrian Sculptures Series.

Art movements, of course, are never tidy chronologies that we can wrap up and rest easy about, secure that we’ve nailed down every aspect. They’re messy and a little bit hysterical, and they’re supposed to be that way. From the Page to the Street serves as a brilliant reminder.

At the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin through Aug. 26, 2018.

2 comments

An important read. Ashamed to say I’m having to put google to work…Thank you.

No shame H. So did I.