Artemisia Gentileschi (Rome 1593–Naples c. 1653), “Judith and Holofernes,” 1612–17, oil on canvas, 159 x 126 cm, Museo e Real Bosco di, Capodimonte, Inv. Q 378

What a moment in Dallas-Fort Worth art museum history….blending old master artwork and contemporary painting in an encyclopedic museum! In an exhibition at Fort Worth’s Kimbell Art Museum entitled SLAY!, two sizable paintings — one created in the 17th century and the other painted 400 years later — appear across from each other. The pairing differs from anything we’re accustomed to seeing at this internationally known institution. When a visitor climbs the Kimbell’s stairs and is confronted by a contemporary painting of a severed, blood-gushing head, you know you’re in for a surprise!

Both artworks are borrowed from other museums and address the familiar biblical tale of Judith and Holofernes: a story that is violent, horrifying, and uncommon. In the early 1600s, female Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi painted the gory story from the Old Testament: Judith and her maidservant visit Holofernes, with the intention of seducing him in order to protect their Jewish town from his planned invasion. The women get him drunk, and then horrifically kill him. Struggling to hold down the warrior, Judith steadies her bloodied knife across his neck to sever his head. Large splashes of blood gush from the scene, rushing down the table in the foreground. The viewer becomes entrapped in the horrific scene; it becomes one you will never forget.

Twenty-first century artist Kehinde Wiley gained attention from the general, non-art world public when he was chosen to paint former President Barack Obama’s presidential portrait. At the time, the announcement of an African-American artist painting the presidential portrait was an unsettling “first” for many.

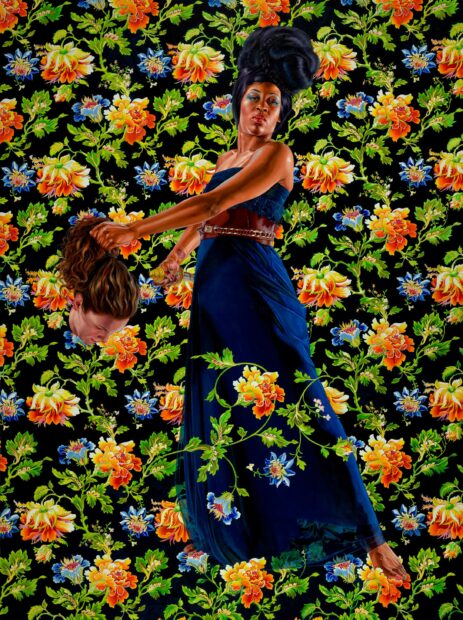

Wiley addresses the same mythical event of Judith and Holofernes in his painting. Depicting women for the first time in his painting practice, Wiley portrays Judith as a dynamic Black female standing in a stark, dramatic frontal stance with her outstretched arms holding the severed head of a white woman. Standing in full-figure, in a high-design Givenchy gown and styled hairdo, the woman is ensconced on a flat-flowered field. The story in both paintings is the same, and while the time and players are different, the artists address the horror in ways that ensure you remember the tale.

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), “Judith and Holofernes,” 2012, oil on linen, Framed: 130 1/2 x 99 7/8 in (331.5 x 253.7 cm), Purchased with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Hanes in honor of Dr. Emily Farnham, by exchange, and with funds from Peggy Guggenheim, by exchange, and from the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 2012. © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of Art and Sean Kelly, New York

Gentileschi’s vision goes beyond the staging of a classical biblical story, through the unfolding of a personal horror in the young artist’s life. Gentileschi grew up as the daughter of an accomplished painter of the day. One evening, a friend of her father came to her home to supposedly pay him a visit. The friend, however, assaulted and raped Gentileschi. A very public court case followed, which caused Gentileschi to be perceived as a social pariah, and she was ousted from her local community. That said, the young artist persevered, continuing to paint in the public arena. Over time, the young talent achieved attention for her most capable artistic work.

Now recognized for her accomplished painting, Gentileschi is heralded as one of the finest 17th century Baroque painters, and certainly the only well-known female among the group. This puts her in an elite group — contemporary recognition of a painter working 400 years prior, especially a female painter, is rare.

Seeing these two dramatic works across from each other in the Kimbell gives the viewer the opportunity to consider the same gory subject matter addressed by artists who painted 400 years apart. This biblical tale carries a deep-seated universal message: a woman can find the strength to do horrific things to save her people, or herself. Could Gentileschi’s work simply serve as a vision of revenge after her brutal rape, or does it further express a fond wish that a woman could rise up and resolve the economic and political turmoil that plagued 17th-century Italy during periodic wars with Spain and France? Does Kehinde Wiley now see the same scene as addressing racial inequality in women’s rise to power today, and comment on the needless deaths happening in our own neighborhoods and school yards? In both of these cases, the answers seem to rest with the artists.

The exhibition is organized by the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Kimbell Art Museum, and The Museum Box. It is on view at the Kimbell through October 9, 2022.

1 comment

I have read another account that said her father hired Tassi to teach her perspective, since she was not allowed as a woman to go to the Art Academy. Tassi raped her while she was under his instruction. Or at least this is the version of the story I read.