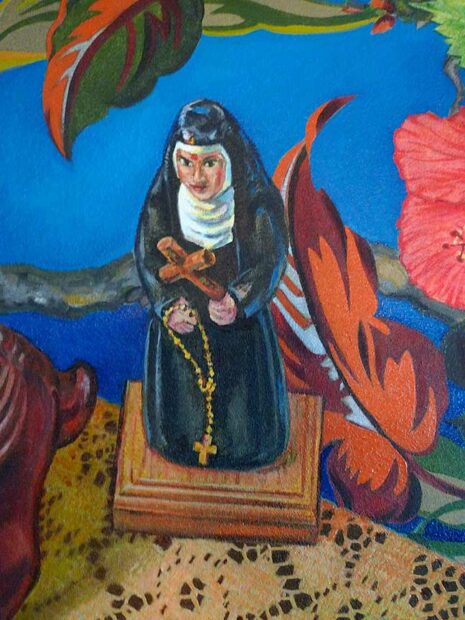

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “The Protagonist of an Endless Story” (detail of upper section), 1993, oil on canvas, 72 x 57 7⁄8 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, acquired 1996. Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

This article is about the friendship between two highly distinguished cultural workers, both of whom relocated to San Antonio. When the Puerto Rican-born painter Ángel Rodríguez-Diaz (1955-2023) encountered the writer Sandra Cisneros at a party in San Antonio, he was struck by her look, and he invited her to pose for him in New York, where Rodríguez-Diaz lived and worked. Cisneros, originally from Chicago, had moved to San Antonio in 1984. By 1993, she was finding success as a writer, and she made frequent trips to New York for readings and to meet with her editor. In time, Rodríguez-Diaz painted two portraits of Cisneros and two paintings of her body parts (her right foot in a glittery shoe, and her right ear with an earring). In addition to her two portraits, Cisneros owned two other paintings by the artist that are now in museums. She also lent objects to the artist for use as props in his paintings, one of which is discussed at the end of this article.

The First Portrait, 1993

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “The Protagonist of an Endless Story,” 1993, oil on canvas, 72 x 57 7⁄8 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, acquired 1996. Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Cisneros recalls the outfit she wore when she met Rodríguez-Díaz: “I was wearing a vintage child’s skirt, a black velvet ‘serve ’em up on a platter’ top, and cowboy boots. Ángel saw me and asked me to pose for him.” She was flattered when the artist praised her “unique look.” Rodríguez-Díaz requested that she wear that specific party-going outfit for the photo session at his Brooklyn studio that would lead to her first portrait. Cisneros’ black skirt was embroidered and sequined. It featured a landscape with palm trees, with a woman in a long dress viewed from behind. Cisneros’ fingers and wrists were bejeweled, and flower-patterned filigree earrings dangled from her ears. To complete the look, a black rebozo was draped around her arms.

After settling in San Antonio, Cisneros had met women who sported what she describes as “a retro Texas look.” These included beautifully textured vintage Mexican skirts, crisply ironed blouses, and sharply pointed cowboy boots. Terry Ybañez and Rose Arriaga (the latter owned a vintage shop) rocked this look, and Cisneros emulated it.

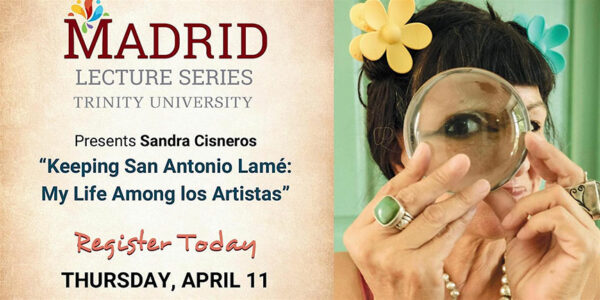

Announcement for “Keep San Antonio Lamé: My Life Among los Artistas,” Madrid Lecture Series, Trinity University, San Antonio, April 11, 2024. Photo: Trinity University

Earlier this year, Cisneros discussed her friendship with San Antonio artists in her lecture “Keeping San Antonio Lamé: My Life Among los Artistas.” The title is a variation of the “Keep San Antonio Lame” meme, which is an ironic invocation to avoid imitating the hipsterism associated with the neighboring city of Austin, whose unofficial motto is “Keep Austin Weird.” Lamé, of course, is a flashy, metal-inflected fabric, and thus, it is the opposite of lame. Moreover, many of Cisneros’ artist friends were gay, adding another layer of meaning to that glittery fabric reference.

In her lecture, Cisneros recalled her consternation when she first beheld Rodríguez-Díaz’s portrait:

Months later, I was flabbergasted to see the result. Here I am with the backdrop of Atlanta burning and an expression on my face like I want to spit in your eye. That’s not me, I thought. All the same, I felt obligated to buy the portrait because he had worked so hard on it and had no money, and I did. But where to put such a huge me? Híjole. Only one wall in my house seemed able to show it to its best advantage, and unfortunately it was in my living room opposite the front windows where I stared out at passersby, fueling the gossip I was indeed that bitch (“Keeping San Antonio Lamé: My Life Among los Artistas,” copyright © 2024 by Sandra Cisneros. Delivered as part of the Madrid Lecture Series, Trinity University, San Antonio, April 11, 2024. All rights reserved. By permission of Stuart Bernstein Representation for Artists).

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “The Protagonist of an Endless Story” (detail of head), 1993, oil on canvas, 72 x 57 7⁄8 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, acquired 1996. Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

This home, located at 735 Guenther St. in the King William district, is in one of the oldest and priciest neighborhoods in San Antonio. When Cisneros had the house painted jacaranda violet with turquoise trim in May of 1997, it instantly became a celebrity edifice known as the “Purple House.” (Even today, when the colors that made it famous are long gone, tourists still search for it.) Some neighborhood residents complained about the colors. The case went to the San Antonio Historic and Design Review Commission, and what would become a long-lasting color controversy immediately became highly public.

This controversy is addressed in Cisneros’ book A House of My Own: Stories From My Life (New York: Knopf, 2015.) in a chapter called “!Que Vivan los Colores!” For Cisneros, these colors represented strength and happiness. She received letters of support from diverse constituencies, including school children, incarcerated prisoners, and even a descendant of Davy Crockett.

Cisneros ultimately had the house painted, a “rosa Mexicana.” (Also see Sarah Martinez, “Sandra Cisneros expressed creativity through books, King William home,” My SA, April 15, 2023) and Dan Solomon, “Sandra Cisneros Sold Her House on Guenther Street,” Texas Monthly, January 15, 2015.)

Contrary to the Texas Monthly article cited above, Cisneros moved into the Guenther St. house much earlier than 1997. She was already in that house when Rodríguez-Díaz’s portrait was delivered to her in 1993.

Sandra Cisneros in front of her portrait in her Guenther St. house living room, San Antonio, 1993. Photo: © Joan Frederick

In the above photograph, dressed in the same outfit she had worn when she posed for Rodríguez-Díaz, Cisneros stands in front of her portrait. As photographer Joan Frederick notes: “Sandra’s hairstyles changed often, so the photo, dated 1993, had to be very close to the same time frame as when Ángel painted the portrait.”

In the above photograph, Cisneros looks directly at the camera, whereas in the portrait, she is captured in a sideways glance. Given her short physical stature, Cisneros looks up at the camera, while, in the painting, she looks down at the viewer. Rodríguez-Díaz, who was much taller than Cisneros, must have gotten down very low to photograph her from such a low angle. He must have chosen this angle in a conscious effort to monumentalize her. Relative to Frederick’s photograph, Cisneros’s painted mouth is narrow and perhaps slightly pursed.

Frederick recalls how the photograph came about: “Sandra and I had gone to an event together, and she had on the same outfit, and I thought: ‘I need to document that.’” She adds: “It was just a quick thought, and as usual with Sandra, she did a great job of clever sarcasm in composing the picture with her pose.” This document was a matter of luck, says Frederick, purely a coincidence, because Cisneros “had a fabulous wardrobe of gorgeous ensembles, and was – and still is – very creative in her fashion choices.”

The effect of the painting was magnified by its visibility. From her front yard, Cisneros told me, passersby “could see the top half of me looking down, with an expression like, ‘get off my lawn,’ as if I was a badass bitch.” Neither in attitude nor in its six-foot-high scale did she relate to the painting. She thought the painting was impressive, but as she emphasized over and over again: “It was not me.” Nor was it an image she wanted to project to the outside world. The portrait created the impression, said Cisneros, that she “was self-obsessed” and egomaniac.

Cisneros did not commission the work, and she had played no active role in the design of the painting, its size, or any other aspect of it. She merely complied with the artist’s directions to wear a particular outfit and to strike the pose he dictated. The monumental portrait wasn’t the sort of thing Cisneros wanted, and it brought her grief. As she informed me: “Its appearance in my living room as I began to gain fame didn’t help in a small town like San Antonio, where there was/is a lot of jealousy and gossip the moment you gain fame.”

In his 2004 Archives of American Art (AAA) oral history interview with Cary Cordova (no relation to me), Rodríguez-Díaz explained that Cisneros’ expression and pose were inspired by a woman in her short story “The Eyes of Zapata,” which was published in 1991.

That woman, Inés Alfaro, is a fictional character in a family whose women are endowed with magical powers. She explains: “The women in my family, we’ve always had the power to see with more than our eyes.” Inés is regarded as a bruja (witch). She was thought to have caused a corn-crop-killing hailstorm when she was a child. Consequently, in years of hunger caused by bad harvests, “they wanted to burn me with green wood.” The villagers killed her mother instead, which caused the family to move (“Eyes of Zapata,” from Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories, copyright © 1991 by Sandra Cisneros. Published by Vintage Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. All rights reserved. By permission of Stuart Bernstein Representation for Artists).

Inés is also a long-term lover of the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. She gives this description of Zapata’s eye as follows: “Your eyes. Ay! Your eyes. Eyes with teeth. Terrible as obsidian. The days to come in those eyes, el porvenir, the days gone by. And beneath that fierceness, something ancient and tender as rain.”

In the quote copied below from the AAA interview, Rodríguez-Díaz gives the impression that the concept of the painting was something of a collaboration between himself and Cisneros:

And then what I did was base the portrait on one of her characters — especially one — the woman in the story of the “Eyes of Zapata” — almost como los de Zapata [like those of Zapata], which is a very intense, tender, and very woman — you know, something about womanhood in that story that is beautiful. And I — it’s sort of like — we use[d] that character to create her portrait and that is why she is standing the way she is standing and that is why, you know, the whole demeanor of it — because I wanted to paint the heroine in that story. And actually, it’s one of my favorite stories because it’s one of the stories where I find that she is the mature woman. And we could go on to other issues about her writing, which I read before doing the portrait so I could sort of get a feeling for her artistic inquiries or things that moved her.

But, according to Cisneros, Rodríguez-Díaz shared neither his compositional nor his iconographic thoughts with her. Rodríguez-Díaz’s other sitters have emphasized the secrecy of his painting process. He took pictures (typically dozens at a time). Afterward, he gave no information about the painting until it was complete. He also declined to let his sitters see the photographs that he took. (If they inquired about them, Rodríguez-Díaz told his models that he planned to destroy them, which he did in nearly every case. I have reviewed the slides Rodríguez-Díaz left behind — which pertain to only a fraction of paintings he made — and I found none of Cisneros.) When the painting was complete, Rodríguez-Díaz would invite the sitter to a dramatic unveiling ceremony, where the artist would reveal the painting by pulling back a cloth.

Had they lived in the same city, Rodríguez-Díaz would no doubt have unveiled the painting per his normal practice. That does not necessarily mean that he would have explained his ideas behind the portrait. I think it’s safe to say that Rodríguez-Díaz intended to endow Cisneros with the ferocious qualities of Zapata’s eyes. Her protagonist, Inés Alfaro, dared to look directly at Zapata when they met, rather than averting her gaze. Moreover, she cast spells over him: “I yanked you from the bed of that other one… I have yanked you from your sleep before into the dream I was dreaming.” She also served as Zapata’s (and symbolically the Mexican Revolution’s) protectress: “I turned into the soul of a tecolote [owl] and kept vigil in the branches of a purple jacaranda outside your door to make sure no one would do my Miliano harm while he slept.”

Rodríguez-Díaz conflated Cisneros with her character Inés Alfaro. She has uncanny insight, she sees what we cannot. As someone deeply concerned with the injustices of colonization, Rodríguez-Díaz created a dramatized portrait of someone who is boldly looking forward, perhaps envisioning a revolutionary potential (social as well as political) that we cannot grasp. This, I believe, is an implied part of the titular “endless story.”

When the Smithsonian contacted the artist and inquired about the portrait’s availability, Cisneros was happy to trade it back to the artist for two of the three goddess paintings he had made in the early 1990s. Rodríguez-Díaz’s spouse, Rolando Briseño, was unaware of this exchange, and I haven’t seen any published reference to it prior to my Glasstire article on the triptych.

In time, Cisneros’ feelings about her portrait changed. “In retrospect, I like the portrait now that I have become more famous,” she told me. Though it initially “caused discomfort,” Cisneros had a more positive attitude towards it after “experiencing envidia” (jealousy), with people “throwing fuel and shade on me.” Part of the problem was contextual. Cisneros did not feel comfortable with the monumental portrait in her home. “It needed to be in a museum,” she concludes.

Cisneros’ reevaluation of the portrait reminds me of a quip attributed to Pablo Picasso, made in reference to his now-iconic 1905-6 portrait of Gertrude Stein (Metropolitan Museum of Art). When he heard that commenters claimed the portrait did not resemble Stein, Picasso reportedly declared: “It will.”

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz with his guest Maricela Sanchez Hunter (right), Mexican First Lady Martha Sahagún de Fox (left), and U.S. First Lady Laura Bush at the “Arte Latino” exhibition, Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, September 6, 2001. The “Protagonist of an Endless Story” hangs behind them. Photo: POOL/AFP

Protagonist of an Endless Story has received considerable exposure as part of the collection of the Smithsonian. It toured nationally as part of “Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum” in 2001. As Jonathan Yorba notes in the catalog:

Standing against a dramatic sky, Cisneros strikes a confident pose… The main character in this visual drama, Cisneros is “nobody’s mother, and nobody’s wife,” as she stated in the author’s note in her acclaimed novel, The House on Mango Street. However, unlike Esperanza Cordero, the young protagonist of Cisneros’ book who grew up on Mango Street – ”a desolate landscape of concrete and run-down tenements” – in this large canvas the author is firmly planted among healthy vegetation that climbs towards an emblazoned sky and presses against the painting’s edges (Arte Latino: Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, New York: Watson-Guptill Publications and Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2001).

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz’s “Protagonist of an Endless Story” appeared on signs soliciting votes, in imitation of political election campaign signs. Photo: Nevada Museum of Art Facebook, July 17, 2019

Some of the exposure that Cisneros’ portrait received was of an unusual nature. In a competition staged for the Nevada Museum of Art, Rodríguez-Díaz’s painting was one of eight that appeared in mock election campaign signs in Nevada in 2019. The eight nominees “from the nation’s preeminent collection of American Art” were described as “vying to represent you on the walls…”

The top three vote-getters (paintings by Childe Hassam, Edward Hopper, and Georgia O’Keeffe) were exhibited in “America’s Art, Nevada’s Choice: Community Selections from the Smithsonian American Art Museum,” which opened November 7, 2019.

Most recently, Cisneros’ portrait was part of “Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea,” a touring exhibition seen in four states and Washington D.C. in 2022-24. “Many Wests” is part of a joint curatorial initiative with the Art Bridges Foundation. The Protagonist of an Endless Story was utilized as the primary publicity image for that exhibition.

The Goddess Triptych

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “The Goddess Triptych” (“The Myth of Venus,” 1991; “Yemayá,” 1993; and “La Primavera,” 1994), with Rodríguez-Díaz (right) and his spouse Rolando Briseño (left), at the exhibition “Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz: A Retrospective, 1982-2014” at Centro de Artes, San Antonio, 2017. Photo: © Ruben C. Cordova

Rodríguez-Díaz’s Goddess Triptych, including the circumstances of its creation from 1991 to 1994, is treated in depth in my Glasstire article “In Focus: Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz’s Goddess Triptych.” Cisneros habitually refers to the three paintings as las Gorditas (the little fat ones), a term she uses con cariño (with love). Rodríguez-Díaz himself alternated between referring to them as las Gorditas and the Goddesses.

As Cisneros noted in my “Goddess” article linked above, Rodríguez-Díaz regarded these women “as beautiful, and I saw them as beautiful, too. They were comfortable in their skin.” This ease was something Cisneros valued highly, because she had to struggle mightily to find this particular comfort. In her short story “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess,” Cisneros recalls:

In high school I marveled at how white people strutted around the locker room, nude as pearls, as unashamed of their brilliant bodies as the Nike of Samothrace. Maybe they were hiding terrible secrets like bulimia or anorexia, but to my naive eye then, I thought of them as women comfortable in their skin.

You could always tell us Latinas. We hid when we undressed, modestly facing a wall, or, in my case, dressing in a bathroom stall… I was as ignorant about my own body as any female ancestor who hid behind a sheet with a hole in the center when husband or doctor called (“Guadalupe the Sex Goddess,” copyright © 1996 by Sandra Cisneros. From Goddess of the Americas/La Diosa de las Americas: Writings on the Virgin de Guadalupe, ed. by Ana Castillo, published by Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. All rights reserved, by permission of Stuart Bernstein Representation for Artists).

Recalling conversations she had with Rodríguez-Díaz, Cisneros told me: “We would talk about how they [the three goddess paintings] were modeled on real women.” This fact was important to Cisneros. The artist also explained how he went about asking each woman to pose in the nude. By that point in time, Cisneros was comfortable with her body. “I was kind of jealous he didn’t ask me to pose in the nude,” says Cisneros. “I had posed that way before. I guess he wanted me in my Southwest badass outfit.”

Joan Frederick remembers that, when speaking about the goddess paintings, Cisneros always declared: “I love them.” Frederick also recalls an instance when she was driving down the street and she and Cisneros saw “a very large woman… with, let’s say, a lot of flesh exposed. I said, ‘That girl should think about wearing a different outfit.’”

Cisneros replied: “I think it’s great that she’s so brave and proud of herself.” Her response made Frederick feel “badly that I had judged the woman in that way, and it taught me a lesson I have not forgotten.”

As noted above, Cisneros traded her portrait back to the artist (who sold it to the Smithsonian) in return for two goddess paintings, The Myth of Venus and La Primavera, which were selected by the artist. Rodríguez-Díaz preferred to keep Yemayá, which was also Cisneros’s favorite of the three goddess paintings. Cisneros donated her two goddess paintings to The San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA) in 2013, when she was preparing to move to Mexico. SAMA acquired Yemayá 2023, and the reunited triptych is the subject of an exhibition through September 14, 2025.

Cisneros hung La Primavera on the staircase wall, which led up to her studio office. It was visible from her dining room. The above photograph was taken at her birthday party in late 1997. Cisneros wears a velvet gown with multiple depictions of flora. Numerous flowers are placed in her hair, amplifying the theme (Spring) of the painting behind her.

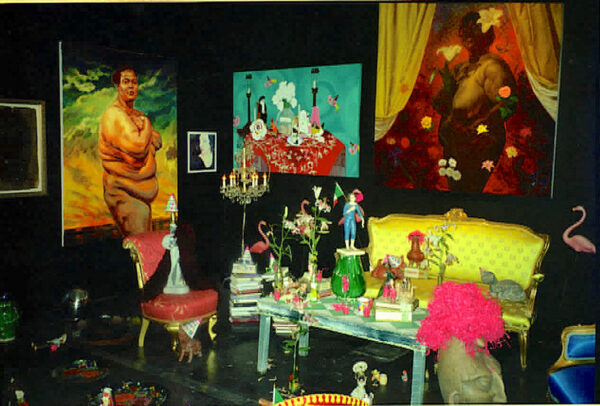

“The Purple House” installation by Franco Mondini-Ruíz at Blue Star (now called Contemporary at Blue Star) with objects from Cisneros’ Purple House, including Rodríguez-Díaz’s “The Myth of Venus” and “La Primavera,” 1998. Photo: © Joan Frederick

Rodríguez-Díaz’s two goddess paintings were displayed in an installation at Blue Star Art Space (now called Contemporary at Blue Star) in San Antonio that addressed the controversy over the colors utilized on the exterior of Cisneros’ Purple House. Cisneros discusses this exhibition in “Tenemos Layaway, or, How I Became an Art Collector.” Her friend, the artist Franco Mondini-Ruiz, was on the Blue Star’s board. As Cisneros puts it, “he could never get his fellow artists to understand issues of race and class” (“Tenemos Layaway, Or How I Became an Art Collector,” from A House of My Own: Stories From My Life, copyright © 2015 by Sandra Cisneros. All rights reserved. By permission of Stuart Bernstein Representation for Artists).

The Purple House installation, along with an accompanying performance by Cisneros, were designed to raise issues of race and class.

Ultimately, Cisneros could not prove that her Purple House’s colors-of-choice were “historical” San Antonio colors. She argued that the decor utilized by Mexicans and Mexican Americans in San Antonio was undocumented, that it was deemed unworthy of preservation and study by the ruling elites, and that it was thus rendered culturally invisible.

For Cisneros, her house, which was also her workplace, was an aesthetic wonderhouse of all of the things that she had gathered together in years of peripatetic wandering. “A house for me,” she wrote in “Tenemos Layaway,” “is about permanence against the impermanence of the universe. Someplace to store all the things I love to collect.” She recalls how she needed to return to her home while her father was dying, which she likened to “the way the thirsty return to water.” Her house and its decor had become a life-sustaining necessity.

Photographs and objects in a small room adjoining the dining room in Cisneros’ Purple House, c. 1998. Photo: © Joan Frederick

Cisneros found inspiration in the houses of her artist friends, including Rodríguez-Díaz and Briseño. As she noted in “Tenemos Layaway,” Cisneros learned that these artists would rearrange “the little objects of everyday” life until, through quotidian alchemy, they had created “beauty that heals.” Rodríguez-Díaz’s goddess paintings served as talismans of women of color who felt secure within their own skins. Consequently, they were important elements of the healing aesthetic of Cisneros’ home.

In a Harvard Review Online of A House of My Own, Laura Albritton argues: “As an artist, she [Cisneros] created homes for herself, houses that she decorated with beautiful and meaningful objects… she created a space for herself in the world where she felt a sense of acceptance and belonging… each home is both a sanctuary and an escape.”

Two Body Parts in the Tienda de los Milagros exhibition, 1997

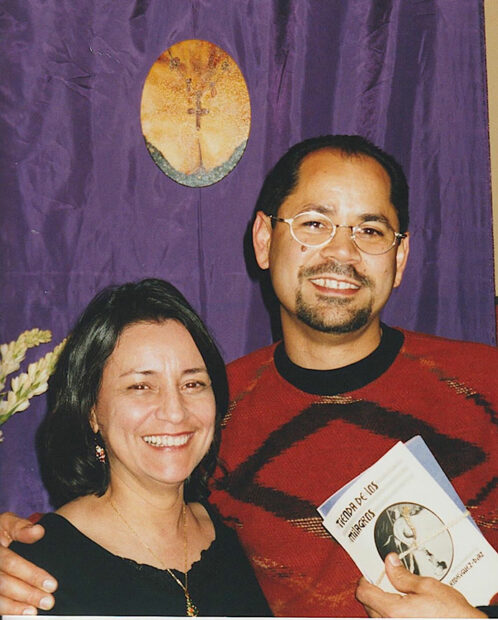

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz (holding promotional materials) with Lucille Morales (Briseño’s sister) at La Tienda de los Milagros opening, 1997. Photo: © Joan Frederick

In 1997-98 (December 13-January 30), Rodríguez-Díaz had his first solo exhibition in San Antonio (he had moved there from New York in 1995). This exhibition of small paintings, called La Tienda de los Milagros, was held at By Marcel, a boutique operated by Norma Bodevin and her daughter Rocío. By Marcel (named after Norma’s son) specialized in upscale women’s clothes and accessories. It also served as a showcase for local artists. The boutique didn’t have sufficient space for paintings on the scale at which the artist normally worked, so Bodevin asked Rodríguez-Díaz to make small paintings. Her idea was to have a show composed of body parts. Bodevin recalls asking the artist to “give me the body in pieces.”

The title of the exhibition was inspired by Tienda de los Milagros (Shop of Miracles), a novela by the Brazilian writer Jorge Amado (published in 1969), which Bodevin had just finished reading. Her concept of body parts as milagros derives from votive offerings made at Catholic churches and shrines. At these sites, worshippers with physical afflictions or infirmities pin small tin images of the body part that ails them (eyes, legs, arms, etc.) to a cloth on an altar or to clothing on a religious statue. These offerings of milagros are made in hope of receiving divine relief. (A tin milagro of an eye is depicted in a still-life painting by Rodríguez-Díaz illustrated at the end of this article.)

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz and David Zamora-Casas (a painting of the latter’s puckered lips is in the center) at La Tienda de los Milagros opening, 1997. Photo: © Joan Frederick

The Tienda de los Milagros exhibition is well-documented. Bodevin has preserved the invitation, the exhibition checklist and its accompanying statement, as well as a clipping of the review in the San Antonio Express-News. Joan Frederick has provided photographic documentation.

A few of the paintings have suggestive titles, such as La ley de deseo (The Law of Desire) and La fruta prohibida (Forbidden Fruit).

In the exhibition statement, Felipe Arevalo likens the small canvases to vanity mirrors, each of which “displays an erogenous zone.” He refers to the latter as “the most coveted areas of flesh.” Arevalo connects the paintings with vanity and lust: “vanity in his composition of private moments of mirror-reflected self adoration, and lust in the lover’s (the viewer’s) glimpse of that fashion enhanced flesh.”

Roger Welch, reviewing the exhibition for the San Antonio Express-News, termed it “a smart installation of thought-provoking, well-painted canvases working with the circumstances rather than being used by it” (“Fashion Statement: ‘La Tienda de los Milagros’ at S.A. Boutique is both playful, spiritually symbolic,” January 29, 1998, p. 1F). Welch refers to the small oval, rectangular, and diamond-shaped canvases as “a glimpse through a keyhole” (p. 3F). Welch further makes a connection between the boutique’s wares as articles of seduction and the subjects of the paintings. He also notes that a painting of the Sacred Heart is hung on a purple cloth, surrounded by actual ex-votos.

Altogether, Rodríguez-Díaz created sixteen paintings of body parts for the exhibition. Three of the small paintings from the Milagros exhibition are discussed in my 2017 Rodríguez-Díaz retrospective catalog, including the Sacred Heart mentioned above, and Raphael Guerra’s ear, which is discussed below (p. 32-33).

Cisneros had a faint recollection that Rodríguez-Díaz had painted one of her ears, while Bodevin thought Cisneros had posed for two paintings and purchased at least one of them. I made inquiries in the art community, and the collector Raphael Guerra recalled that Phil and Suzanne Arevalo had a painting of Cisneros’ foot in a shoe. As it turned out, the Arevalos had bought both the foot and the ear. The exhibition had sold out on opening night, which is why Cisneros was unable to buy either painting for which she had served as a model.

Guerra posed for a painting while wearing a clip-on earring. It was painful, and he asked Rodríguez-Díaz to quit taking photos after 20-30 shots. Guerra asked to see the photos, but the artist told him he was going to destroy them.

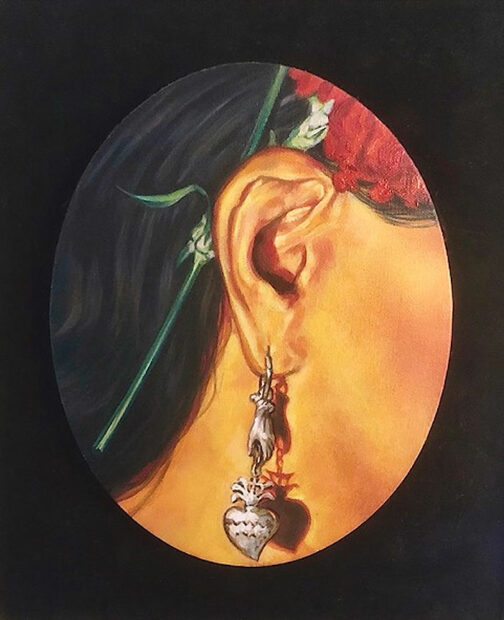

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “Sandra: Listen Up! ¡Escuchame!,” 1997, 8 x 10 inches, oil on canvas, collection of Phil and Suzanne Arevalo. Photo: courtesy of Phil and Suzanne Arevalo

Sandra: Listen Up! ¡Escúchame! was used for the Tienda de los Milagros invitation. It focuses on her right ear, which has a carnation tucked behind it, though the top of the blossom is cropped by the edge of the oval. Cisnernos’ silver earring is doubly engaged with the milagro theme: it features a hand, and a flaming Sacred Heart dangles from it. The heart and hand cast dark shadows, and the inner portion of the ear is in dark shadow, testament to the dramatic lighting effects that fascinated the artist (a product of his admiration of Baroque era painting).

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “Nuevo Laredo Glamoroso,” 1997, 8 x 16 inches, oil on canvas, collection of Phil and Suzanne Arevalo. Photo: courtesy of Phil and Suzanne Arevalo

Cisneros bought the shoe featured in the above painting for her 40th birthday, which she celebrated with friends in the Texas border town of Nuevo Laredo. She remembers seeing the shoes in a window, when the group was on their way to dinner. Cisneros didn’t buy the pair because she thought they were beautiful or glamorous. On the contrary, she bought them because they were “so ugly.” In her estimation, this was “the kind of shoe a drag queen or prostitute would wear.” Consequently, she purchased it “as a ‘costume’ shoe, not as a shoe I would wear for fashion.”

Her photo shoot with Rodríguez-Díaz was the only time Cisneros ever wore the shoes. Cisneros doesn’t recall the ankle bracelet, which may have been a prop provided by Bodevin. The gold medallion was perhaps meant to refer to a milagro. Or, on the other hand, it might have been a symbol of money-for-sex. In a supreme evocation of dubious taste, the dark, glitzy, heeled sandal clashes with the white fur visible above Cisneros’ ankle, which must have been the bottom of a full-length fur coat.

Once again, Rodríguez-Díaz has employed dramatic lighting, with the heel casting a funnel-like shadow. Following his normal practice, he must have taken many photographs in order to find the composition he wanted to replicate in paint. At this point in his career, the artist was seeking a heightened degree of realism (which is also evident in his second portrait of Cisneros, painted two years later, which is discussed below).

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “Nuevo Laredo Glamoroso” (detail), 1997, 8 x 16 inches, oil on canvas, collection of Phil and Suzanne Arevalo. Photo: courtesy of Phil and Suzanne Arevalo

Unlike fashion photographs and conventional portraits, which always smooth over or airbrush tensions and signs of stress and strain, Rodríguez-Díaz has chosen to highlight the stresses that the shoe places on Cisneros’ foot and ankle. Muscles, tendons, and bones form bulges above the strap, and a large indentation in which the medallion rests. One can also see wrinkles in the skin behind the Achilles tendon where the shoe has caused the foot to bend in considerable torsion.

By replicating these stresses, Rodríguez-Díaz depicted details that artists have habitually evaded, ignored, or effaced. Peter Paul Rubens, the great Flemish Baroque painter who was much admired by Rodríguez-Díaz (see my Glasstire Goddess article noted above), also depicted details that had been largely ignored in earlier art. He was criticized for depicting the curvature of human shins, since straight shins were good enough for earlier masters. As I noted in the Goddess article, I have seen visitors in European museums laugh out loud in front of certain paintings by Rubens. Contemporary viewers are particularly incredulous before paintings in which large women (by today’s standards) are presented as sexually desirable (as graces, goddesses, etc.) and not as objects of ridicule (such as embodiments of sloth, gluttony, or large bodies tumbling into Hell in a Fall of the Damned).

Peter Paul Rubens, “The Little Fur” (detail of knees), c. 1636–38, oil on canvas, 69 x 32.6 inches, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo: Google Arts and Culture

There are peculiar sources of amusement for spectators who find Rubens’ big women laughable. What sets them off above anything else are the small dimples Rubens painted in the area of the knees, which the artist depicted as lovingly as he rendered small pockets of cellulite. The detail above is from a painting of Rubens’ young wife, Helena Fourment, who was regarded as a great beauty. (See my Goddess article for a discussion of the painting and a full image.)

Peter Paul Rubens, “The Three Graces” (detail), c. 1630–35, oil on oak panel, 86.8 × 71.6 inches, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Photo: Google Arts and Culture

One can also see similar dimples in the above detail of Rubens’ Three Graces, which is also reproduced in full in my Goddess article. It is thought that Helena modeled for the leftmost grace.

Rodríguez-Díaz reproduced the various wrinkles, flexed tendons and muscles, and the jutting bones caused by the stress of wearing a high-heeled shoe. I think he was consciously emulating Rubens’ example by depicting particular physical traits that other artists had preferred to ignore. Rembrandt’s (and before him Titian’s) depictions of sexualized large women, for instance, were more generalized than those of Rubens, who made very precise sketches of human anatomy. Rodríguez-Díaz, who used a camera to create modern counterparts to sketches, chose to closely follow a photograph that highlighted stresses in Cisneros’ foot and ankle.

Like Rubens before him, Rodríguez-Díaz found beauty in particularity – including particularities that other artists had not endeavored to capture. Richard Arredondo, an artist friend of Rodríguez-Díaz, noted to me that the latter often had very emotional responses when he beheld Latina women. He would proclaim the beauty of “nuestra raza” (our race), often with teary eyes and a broken voice. His desire to capture this beauty extended down to the smallest details.

In Nuevo Laredo Glamoroso, Rodríguez-Díaz appears to utilize a blonder tonality for Cisneros’ skin than he did in Sandra: Listen Up!, as well as in his second portrait of Cisneros, and in his other contemporary depictions of Latinx sitters. At the same time that he was making allusions to the anatomical peculiarities/particularities found in Rubens’ work, perhaps he was also alluding to the colors utilized by Rubens. Finally, Rodríguez-Díaz’s sketchy technique in Nuevo Laredo Glamoroso more closely approaches the techniques found in some sketches by Rubens and by his student Anthony van Dyck (their work was sometimes confused) than in other works he painted. Therefore, on several levels, I think Nuevo Laredo Glamoroso can be viewed as an homage to Rubens.

La Guadalupana, 1999

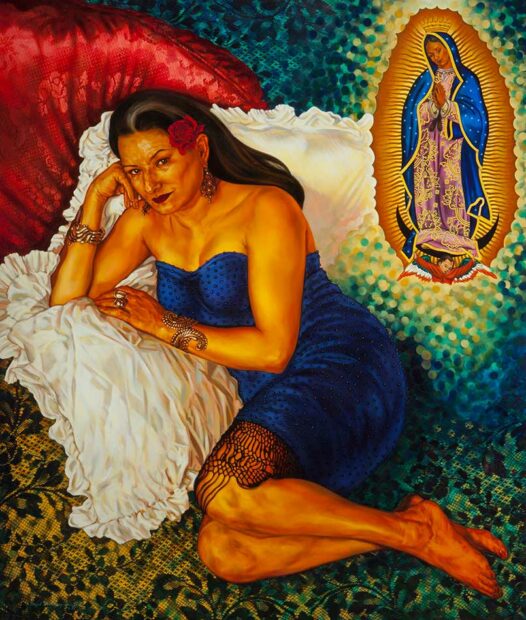

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “La Guadalupana,” 1999, 64 x 54 inches (framed), oil on canvas, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2003.28, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in memory of Alfredo Cisneros del Moral. Photo: Michael Tropea

Rodríguez-Díaz’s second portrait of Cisneros, La Guadalupana of 1999, blends photo-realism and supernatural apparition. Cisneros, who is apparently sitting on the floor, leans against a large white satin pillow, which is perched on a sofa. The Virgin of Guadalupe miraculously appears in the upper right, surrounded by tiny, brightly-colored spheres. The scalloped edge of her mandorla eclipses the right side of Cisneros’ large, strange pillow. Cisneros’ detailed face and legs must closely follow the photograph Rodríguez-Díaz took of her. Yet, in the lower left, the space does not seem to be continuous with Cisneros’s body, the pillow, or the sofa. It is as if the Virgin’s image confounds and scrambles the putatively “real world” space into which it has descended.

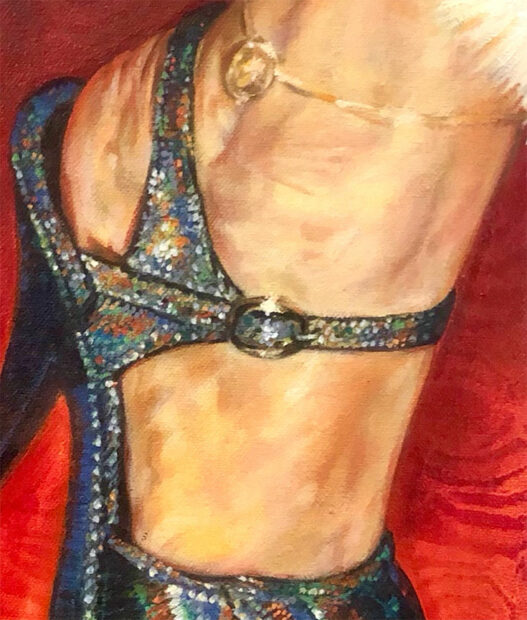

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “La Guadalupana” (detail of upper body) 1999, 64 x 54 inches framed, oil on canvas, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2003.28, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in memory of Alfredo Cisneros del Moral. Photo: Michael Tropea

Cisneros gave me this assessment of La Guadalupana: “He painted another portrait of me, and I liked it even less [than Protagonist of an Endless Story].” By this point in time, Rodríguez-Díaz liked to make skin glisten. “He always made it look like it was 100 degrees, and every sweaty pore came out,” laments Cisneros, who thought the portrait made her look “like a cantinera” (barmaid). “I never liked it,” she added, “but I never told him, because I never wanted to hurt his feelings.”

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “La Guadalupana” (detail of head) 1999, 64 x 54 inches framed, oil on canvas, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2003.28, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in memory of Alfredo Cisneros del Moral. Photo: Michael Tropea

In this portrait, Rodríguez-Díaz is seeking to capture a more detailed and more naturalistic head and face, in comparison to those he had rendered earlier in the decade, such as in the three goddess pictures. The unusual disposition of Cisneros’ right hand, with dangling fingers and a sharply creased, abbreviated palm, no doubt reflects how it was captured by Rodríguez-Díaz’s camera. So, too, did the artist replicate the particular features of Cisneros’ left ear.

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “La Guadalupana” (detail of legs) 1999, 64 x 54 inches framed, oil on canvas, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2003.28, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in memory of Alfredo Cisneros del Moral. Photo: Michael Tropea

In the areas of Cisneros’ knees, shins, and feet, Rodríguez-Díaz has depicted flexed muscles, protruding bones, and wrinkles with a precision that is very uncommon in painting. Like the Baroque master Rubens, and similar to Nuevo Laredo Glamoroso (as discussed above), Rodríguez-Díaz took pains to render details that other painters ignored or effaced in the service of conventions of beauty, idealization, or propriety. This obsession with unusual details was part of his credo as a photorealist. I believe it was also part of his quest to capture what he regarded as “real” beauty, as opposed to idealized or conventionalized notions of beauty.

In general, during the 1990s, Rodríguez-Díaz’s portraits and self-portraits became increasingly precise and detailed. (See my retrospective catalog). Rodríguez-Díaz replicated the images he captured on slides. When he painted strange or unusual features, we can be certain that he deliberately sought them out with his camera, since he was such a diligent and obsessive photographer when it came to his source material. I argue below that, in this particular portrait, his heightened realism, his unvarnished replication of the visible and the particular, served an important iconographic role in La Guadalupana.

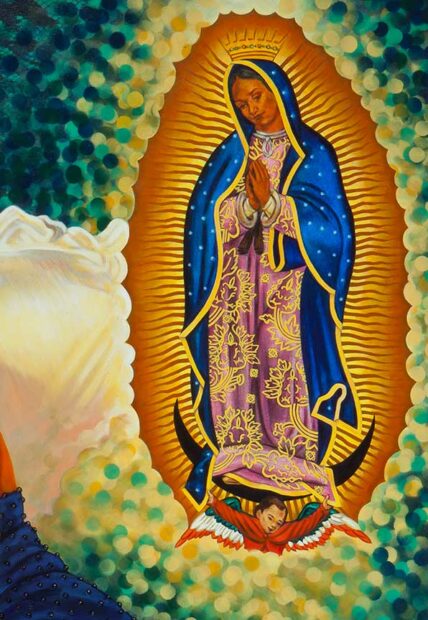

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “La Guadalupana” (detail of Virgin of Guadalupe) 1999, 64 x 54 inches framed, oil on canvas, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2003.28, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in memory of Alfredo Cisneros del Moral. Photo: Michael Tropea

Rodríguez-Díaz painted the figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe with a high degree of clarity, as well as saturated colors. The face of the Virgin is unusually vivid. One senses that, rather than a remote icon or a generalized, soft-focus figure of ideal beauty, her facial image is based on – and is meant to represent – a real woman, one with a high percentage of indigenous blood.

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “La Guadalupana” (detail of Virgin of Guadalupe’s head) 1999, 64”x 54” inches framed, oil on canvas, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2003.28, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in memory of Alfredo Cisneros del Moral. Photo: Michael Tropea

The faces of Cisneros and of the Virgin of Guadalupe are sufficiently close in this painting that one can be confident that Rodríguez-Díaz was drawing a parallel between the two. This resemblance was a way of representing Guadalupe as a real woman, and conversely, Cisneros as a goddess. In this respect, the artist reflected a crucial aspect of Cisneros’ conception of Guadalupe. Her essay “Guadalupe the Sex Goddess” is behind Rodríguez-Díaz’s decision to combine Cisneros and Guadalupe.

In terms of paint tones, this portrait appears to be Rodríguez-Díaz’s darkest depiction of Cisneros. Cisneros is deeply concerned with the Virgin of Guadalupe because, as she notes in her Guadalupe essay, she is “overwhelmed by the silence regarding Latinas and our bodies.” Cisneros had a longstanding hostility to Guadalupe, which served as an impossible cultural role model. Cisneros elaborates her objections:

I was angry for so many years every time I saw a la Virgen de Guadalupe, my culture’s role model for brown women like me. She was damn dangerous, an ideal so lofty and unrealistic it was laughable. Did boys have to aspire to be Jesus? I never saw any evidence of it. They were fornicating like rabbits while the Church ignored them and pointed us women toward our destiny — marriage and motherhood. The other alternative was putahood [whorehood].

In her essay, Cisneros collapses and telescopes the Virgin of Guadalupe into various female Aztec deities, explaining that she is not interested in the foundational mythic apparition of 1531, but rather in the contemporary Guadalupe, which she describes as the one “who has shaped who we are as Chicana/mexicanas today, the one inside each Chicana and mexicana.”

In her essay, Cisneros explains how she came to accept Guadalupe by creating a new conception of her:

My Virgen de Guadalupe is not the mother of God. She is God. She is a face for a god without a face, an Indigena for a god without ethnicity, a female deity for a god who is genderless, but I also understand that for her to approach me, for me to finally open the door and accept her, she had to be a woman like me.

Cisneros also states her certainty that Guadalupe “is not neuter like Barbie. She gave birth.” By emphasizing Cisneros’ physical characteristics, Rodríguez-Díaz affirms – in the most material way that he can – that she, too, is a real woman.

Cisneros concludes her Guadalupe essay with this sentence: “Blessed art thou, Lupe, and, therefore, blessed am I.” The two women are thus conjoined as corporeal, palpable, and authentic beings, which is why Rodríguez-Díaz unites them in this painting.

At the Turn of the Century In San Antonio, 1998

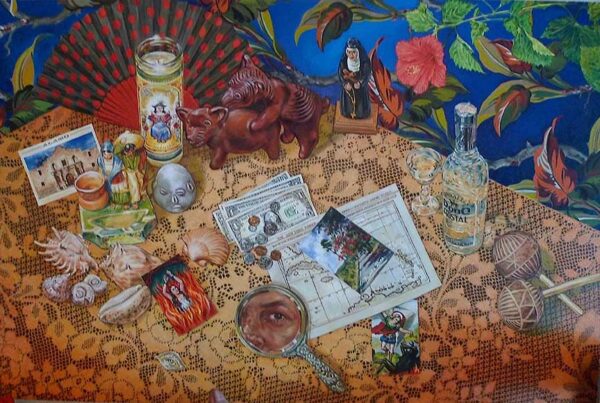

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “At the Turn of the Century In San Antonio,” July 1998, acrylic and oil on paper mounted on linen, 32 x 48 inches, collection of Dr. Raphael and Sandra Guerra. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Among the reasons Cisneros and Rodríguez-Díaz bonded were their mutual love of animals. “We were both animal intuitives. We loved animalitos,” recalls Cisneros, who refers to the artist as un hombre muy dulce” (a very sweet man). She also remembers lending the artist some of the objects he used in his still-life paintings.

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, “At the Turn of the Century In San Antonio” (detail), July 1998, acrylic and oil on paper mounted on linen, 32 x 48 inches, collection of Dr. Raphael and Sandra Guerra. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

One of these props was utilized by Rodríguez-Díaz in a very humorous fashion. At the upper center of the still life, two dogs (in the form of a reproduction of a sculpture from Colima, Mexico) are mating feverishly. This vigorous activity is causing the table to shake, which is transporting the statue of St. Teresa over the edge of the table. She is about to fall off of it completely. Of all possible saints, St. Teresa (Teresa of Ávila, a 16th-century Spanish nun) was chosen, no doubt, because her “ecstasy,” famously depicted by the Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, has often been likened to sexual climax. The following passage is St. Teresa’s account of her encounter with a beautiful, flaming angel

… who seem to be all on fire… In his hands I saw a great golden spear, and at the iron tip there appeared to be a point of fire. This he plunged into my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he pulled it out I felt that he took them with it, and left me utterly consumed by the great love of God. The pain was so severe that it made me utter several moans. The sweetness caused by this intense pain is so extreme that one cannot possibly wish it to cease, nor is one’s soul content with anything but God.

Dr. Raphael and Sandra Guerra, the preeminent collectors of Rodríguez-Díaz’s paintings, appreciate this connection. They purchased At the Turn of the Century In San Antonio from the artist, and they also acquired the pair of mating Colima dogs from Cisneros. The two works are exhibited in close proximity to one another in their house.

Far from being an ordinary still life, At the Turn of the Century In San Antonio makes multiple references to Santería as well as to Catholic religions (additionally, in Mesoamerica, dogs guide souls through the underworld to the ultimate resting place). In this painting, which was intended for his ArtPace installation, Rodríguez-Díaz also references the Spanish-American and Mexican-American wars of conquest. (I have included the text of my catalog entry on this painting in the Appendix below.)

Last Meeting

The above photograph dates from the year Rodríguez-Díaz moved to San Antonio. Cisneros saw less of Rodríguez-Díaz after she moved to San Miguel de Allende in 2013,

“The last time I saw him,” recalls Cisneros, who encountered the artist in a cafe in San Antonio (probably around 2020), “his memory was already gone.” She adds: “He knew me, but he didn’t know where from.”

“But I could feel his love,” Cisneros emphasizes. “There was just this overflowing love. I still love Ángel.”

***

Appendix

Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz, At The Turn of The Century In San Antonio, July 1998, acrylic and oil on paper mounted on linen, 32 x 48 inches, collection of Dr. Raphael and Sandra Guerra.

Though it was made in anticipation of Rodríguez-Díaz’s 1998 installation at Artpace, which coincided with the centennial of the Spanish American War, this painting did not become part of it (see the text for El Chupacabra for more information). The map and the postcard of Cuba are understood in parallel with the postcard of the Alamo: they symbolize the Spanish American and Mexican American Wars. Even the amount of money on the table has symbolic value: the bills and coins total 1898 cents.

The still life objects also represent the artist’s social network, since many were gathered from various friends, and many of them reference places Rodríguez-Díaz has lived. He loves sand, the beach, and seashells. He chose Don Q Cristal [a white rum] because it is made near his native city.

Rodríguez-Díaz’s mirrored self-portrait forms the lower point of a circle of objects. The tin milagro eye serves as the artist’s other eye. The card with the Anima Sola (Soul in Purgatory: woman in flames being cleansed of sin before being able to enter heaven), the cement sculpture of a head with cowrie shell eyes, and the candle of the Santo Niño de Atocha are all related. In the Caribbean Santeriá religion, they are all manifestations of Eleguá, who originated in Africa as the Yoruba trickster god of crossroads.* The artist owns this image of Eleguá, whom he says “watches the door and protects the house. You have to give him candy.” Rodríguez-Díaz included the card with St. Michael vanquishing Satan because he likes its eternal imagery: “It’s always the battle for souls.” On a humorous note, the mating dogs, borrowed from noted author Sandra Cisneros, are shaking the table, which is causing the statue of St. Teresa to fall from the table. Consequently, this is not such a still life, after all.

* “Eleguá, Lord of the Crossroads,” About Santería website. http://www.aboutsanteria.com/eleguaacuteeshu.html

From: Ruben C. Cordova, Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz: A Retrospective, 1982-2014, San Antonio: City of San Antonio, Department of Arts and Culture, 2017, p. 51.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated or co-curated 34 exhibitions. In 2017, he organized three exhibitions devoted to Rodríguez-Díaz: the retrospective at Centro de Artes; and, at FL!GHT, “Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz: Nueva York-San Antonio” and “Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz: El Mero Chile/The Full Monty.” His latest exhibition, “Dining with Rolando Briseño: A Fifty Year Retrospective,” is at Centro de Artes (the former Museo Alameda) in San Antonio through February 9.

2 comments

Enjoyed reading about the artist and the subject, and her reaction to each portrait. Not surprising to hear that the subject had qualms about the result, as women are often keenly sensitive to their depiction for lots of cultural reasons, were as men (for the most part-excluding certain presidents) are less so, usually having a “take it or leave it” shrug reaction to their depictions.

I’ve attempted a few portraits myself in the past, so am sympathetic to the complexity of “reactions” on the part of the subject vs artists vision or intent.

Cisneros was a trouper in accepting both portraits in spite of her complex reactions, and then finding a positive way to have them appear in public collections later on for others to enjoy looking at…along with her goddess gifts to SAMA. Lots of other interesting historical details as well.

dave, Cisneros thought it was important to support Latinx artists, and Angel was one of the beneficiaries of her patronage.