Growing up in North Texas, I used to think that the local landscape of patches and plains of tall grass wasn’t much to look at. But after visiting a recent exhibit at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, it turns out I hadn’t been looking with careful attention.

Trespassers: James Prosek and the Texas Prairie features more than twenty artworks — watercolor paintings, sculptures, and silkscreen paintings — created over the past two years for a project examining the various plant species found in Texas’ prairies and grasslands.

James Prosek (b. 1975), “Burned log with flower (Prairie Paintbrush),” 2023, bronze, clay, oil and watercolor. Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York. Photo: Argenis Apolinario, © James Prosek

Many of us probably haven’t looked at grass closely before. Through life-sized watercolor paintings, artist and naturalist James Prosek not only makes the task easy, but also mesmerizing and rewarding. Standing in front of a painted representation of a stalk of Yellow Indiangrass, I start to notice all the variation of color in the stem alone.

The amount of detail Prosek provides in each painting is a testament to his passion and reverence for nature. “I love these plants. I think drawing them is a way to express my devotion to them. It’s a cycle. The passion for the plant brings me to want to draw it, and drawing it makes me like it even more,” he says.

I think Mary Oliver said it best: “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

Prosek’s devotion to the natural world has been the basis of his artistic career for decades; he’s even keept an outdoor journal and sketchbook since he was eleven. As a young boy growing up in Connecticut — where he still lives and works — Prosek practiced drawing by copying the works of naturalists like John James Audubon, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, and Roger Tory Peterson. For Prosek, drawing has been a tool for strengthening his observation skills.

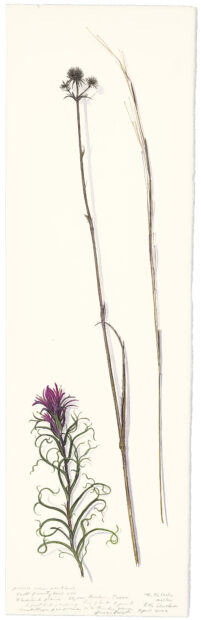

James Prosek (b. 1975), “Rattlesnake Master, Prairie Paintbrush, and Little Bluestem, Clymer Meadow, Blackland Prairie in a thunderstorm, Celeste, Texas,” April, 2022, graphite, watercolor, and gouache on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York, © James Prosek

As I walk through the exhibit, each painted specimen feels tangible, its illusion of dimension reinforced by lavender gray shadows. When was the last time you looked deeply at a shadow? Quickly after starting this project, Prosek became fascinated by them: “The grasses and their shadows are so lyrical. They almost look like handwriting. When you put a specimen on a piece of white paper the shadows they create are like a signature. The shadows help you see the elegance of the forms and vice versa, the grasses help you see the elegance of the shadows. That’s something I hadn’t thought about before.”

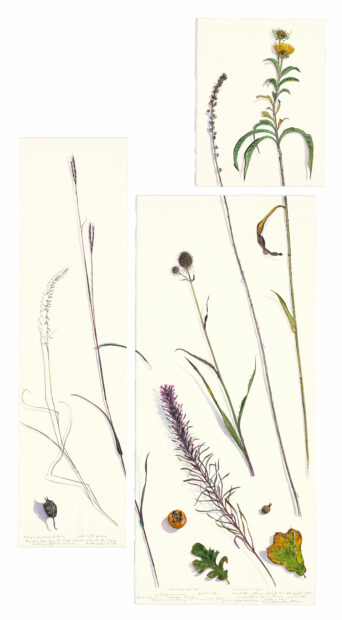

James Prosek (b. 1975), “Liatris (Gayfeather), Blackjack Oak, Post Oak, Maximilian Sunflower after a rain, between Forestburg and Greenwood, Texas,” November, 2022, graphite, watercolor, and gouache on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York, © James Prosek

Prosek’s watercolors capture the delicacy of each stalk of prairie grass. They look thin and wispy, and yet each exudes a sense of strength from its sheer size. Some of the paintings nearly stretch from the floor to the ceiling! The artist had brought pieces of paper out into the prairies to draw onsite and quickly realized that many of the tall specimens would require multiple sheets.

Each finished watercolor extends over several boxed frames, the hanging of which is a visual arrangement mimicking the evolution of prairie lands today, something Prosek discerned during his travels: “When I was staying near Clymer Meadow, a remnant prairie northeast of Dallas, I was looking at a map of the property and noticing the grids, the boxes that make up the properties of prairie lands. The grid of boxes on the wall [of the exhibit] are meant to resemble what the prairies have become. We’ve taken an interconnected nature and fragmented it into pieces.”

James Prosek (b. 1975), “Great Coneflower, Eastern Gamma grass, Purple Coneflower, Blackland Prairie, Clymer Meadow, Celeste and Campbell, Texas,” June, 2022, graphite, watercolor, and gouache on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York, © James Prosek

During the two years of research for this project, Prosek traveled throughout the state to more than a dozen sites, visiting places in the Hill Country like Honey Creek State Natural Area in Comal County, Shield Ranch outside of Austin, Bamberger Ranch Preserve near Johnson City, places in North Texas like Clymer Meadow Preserve in Hunt County. He even went out into the stretches of Far West Texas to the Davis Mountains State Park.

The people Prosek met along his journey changed the way he viewed the land. He says, “The landowners and ranch managers I met were extremely welcoming and were hugely passionate about grass and wildflowers. I never encountered a culture where people were so jubilant about grass. Texas has a deep history with grass. But not just Texas! What I learned on my first trip to the Hill Country is that the big four prairie grass species — Big Bluestem, Little Bluestem, Indiangrass, Switchgrass — are also native to Connecticut.” He continues, “Later, when I returned home, I found all four grasses around my house. The project has taught me a lot about my own backyard, which was totally unexpected.”

Certainly on the surface one could clearly identify Texas as a different landscape from Connecticut. Yes, the ecosystems are different, and yet, like with different groups of people, you can find many commonalities that connect them.

James Prosek (b. 1975), “Yellow Indiangrass, White Heath Aster, Goldenrod, Straw-colored Flatsedge, Easton, Connecticut,” October, 2022, graphite, watercolor, and gouache on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York, © James Prosek

With projects like Trespassers, Prosek attempts to build bridges between the worlds of natural science and the arts. “I feel like there’s value in cross-disciplinary work because you’re pushing people outside their comfort zones,” he says. And certainly this collection of artwork provokes conversations about our ongoing loss of these native ecosystems and the importance of preservation. By creating painted portraits of Texas plants, Prosek not only connects us to the individual beauty of each stem of grass, but also helps us to appreciate the Lone Star State’s rich ecological life that’s worth saving.

Trespassers: James Prosek and the Texas Prairie is on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth through January 28, 2024.