If one wanted to be withering with themselves and others, they could ascribe a sort of window on the soul based on what changes to their life someone did or didn’t make during this long pandemic. Did you make positive changes — a new diet and exercise regimen; a new disciplined work routine? Did you gaze upon this vastly strange time, the future dragging us along screaming, and respond like Rilke gazing upon the torso of Apollo?:

“Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.”

My answer to all this is a resounding no. My main life change was watching more movies and getting back into CDs as a preferred audio medium. This is why I’m particularly awed by people who have used this chunk of solitude as a currency, and spent it wisely instead of frittering it away on the slot machines of streaming and social media.

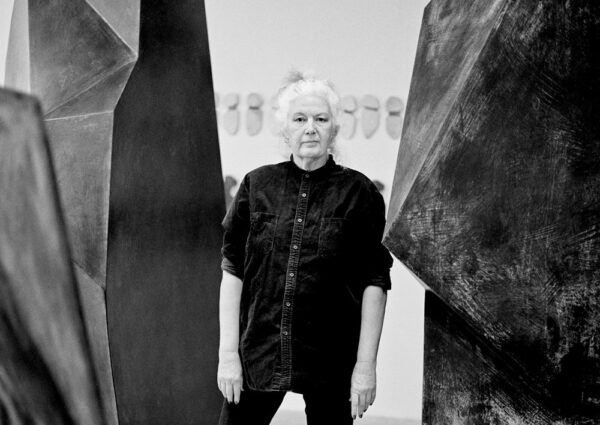

This is exactly what Texas-based artist Catherine Lee did. Lee is primarily known for her striking array of abstract works — series of amphora-shaped shards in different interlocking materials (bronze, stone) resembling precious keys to an ancient antechamber, or the stone sentries placed to guard the door; mosaic wall pieces of intricate tiled patterns; large, free-standing sculptural works in patchwork patterns. It would be inaccurate to describe Lee’s works as defying meaning and content; there is much to dig into. The choice of materials such as copper, the historical associations with the amphora shape, the emotional tenor of the colors used, and so on. But for the most part, Lee’s works have not been literary, or imbued with direct text — until now with her new project.

Lee resides on an almost impossibly idyllic property just outside of Wimberley. She used to split her time between Texas and New York, but in the past decade has became a full-time Texan (she was born in Texas). Wimberley, in the heart of Hill Country, is geographically a prime jewel of the state, with emerald rolling hills, limestone cliffs, rivers, and sparkling natural springs and swimming holes. It’s where I take out-of-towners whose impression of Texas is a bleak, existential expanse of desert sizzle and pumpjack metronome (as in E. Emmet Walsh intoning “Down here you’re on your own,” or Tommy Lee Jones sighing, “Man has to put his soul at hazard, has to say… okay, I’ll be part of this world.”).

Lee’s property is an almost platonic idea of a bucolic artist’s retreat. The main house is filled with books and albums and verdant plants and softly whooshing ceiling fans; in the backyard there is a rectangular lap pool that Lee used to recover from a car accident, and then down the hill is Lee’s expansive studio. It looks out over a gently sloping, foliage-rich ravine. It’s easy to imagine a Joanna Hogg or Lisa Cholodenko movie set here; the light and ambient sounds of nature create an atmosphere that is not just cinematic but in media res. There is an absolute serenity, but things are happening. This contrasts to one’s (or at least my) city life, which can sometimes feel like a claymation loop of a Lucian Freud painting, as if you live in a doll’s house and are static unless an unseen hand moves you around.

These days, it’s difficult to be in nature without a twinge of elegy or dread. You know, deep down, that now every season feels a little different, a little worse, because it is. The Texas freeze in February, the rolling heat domes, the use of the word “obscene” in weather reports, how when you go to California the land and trees and grass can be almost heard audibly drying, like when you put a wet log on the fire. The videos taken from the eyes of biblically large hurricanes, and it sounds like the creepy children’s choirs they play in the trailers of horror movies — we all feel it even if we pretend we don’t.

And so this feeling tragically but necessarily hits harder with the axe, at the frozen lake of our hearts, when in outdoor splendor. It struck me when I visited Lee recently, and I imagine it strikes her quite often.

There are terms for this feeling: eco-anxiety, eco-dread, and more poetically, solastalgia. I find most art I look at now is hued with it, an anxious hum hovering around it all like the cicadas that came out this year. I recently made my first visit to the MFA’s Kinder Building in Houston and marveled at Christina Iglesias’ Inner Landscape, a staggering bronze sculptural pool outside one entrance. Iglesias describes the piece as “a portal to the underground, to the nature of the Earth, and to the strata of memory,” which it certainly is, and possesses a tuning fork chime to the eternal. But after that is an ominous resonance. The bronze looks like lacquered, petrified wood. It looks like some ineffable prophecy; the petrified future.

There’s was the same dark ballast in the epic, surrealist masterwork exhibition Specters of Noon by Allora & Calzadilla that recently closed at the Menil in Houston. Encompassing surrealism and Christian mysticism, the multimedia (you could describe it unironically as “immersive”) work centers around entelechy (the realization of potential), a coal-forged sculpture cast from a tree struck by lightning. The ceiling’s audiophile-grade speakers play a lush, melancholic soundscape composed by David Lang. The effect is a blunt rush, like when wood snaps or ice breaks off, or a gasp you make when wake up from a nap stung by a gorgeous, etched nightmare.

In this age of the social practice, there is a natural reflex with art that engages a crisis to wonder to what end the work serves. I am always reminded of the devastating Kurt Vonnegut quote: “During the Vietnam War, every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.” Climate crisis requires a sci-fi movie level of global cooperation and government intervention. All the unprecedented wildfires, hurricanes, mudslides, heat waves, freezes, and all the other disaster tropes, wriggling alive like the monster in Frankenstein (and outraged that man could be so foolish and arrogant to unleash this) hasn’t much moved the needle much. The Green New Deal, an honestly conservative and reasonable proposal, is DOA, mocked by the elderly Democratic leadership who seem serene in their confidence that they will die while their vacation homes are still Architectural Digest-ready at sunset. But these days, who’s to say? The deadline keeps getting pushed up.

What is art to do in the face of apocalypse? What can it do? Certainly not activate the massive material change required. I bristle these days at art made of literal trash, art that is purposefully jittery, grotesque, that emulates and processes the “way we live now.” I hate the way we live now — it’s gross, wasteful, debased, neurotic, and not terribly interesting. Being distracted and anxious all the time does not have the same grave elegy of Max Von Sydow in Winter Light. Which is to say, that perhaps it’s enough to create art that is sad and beautiful and clear-voiced; perhaps the best an artist can do is be the tormented, castrated child soprano in The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, lamenting the wreckage.

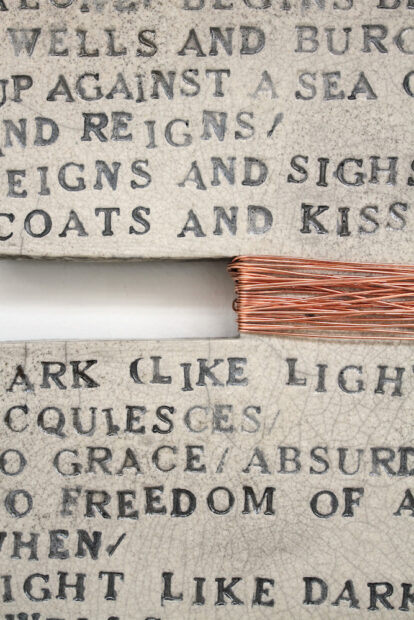

Lee’s environmental works consist of amphora shapes separated at the neck by coil copper wiring. Lee then, through a painstaking embossed-ink process, inlays the letters of her poems into the stone tablet portion of the amphora. The effect is telescopically ancient; these works yearn to persevere and be discovered — some blown dust future when these words ring like dark psalms. Lee then reads her poems on her Instagram page. Lee reads clearly but with a downhill velocity, a rollicking wave and plunge in the wine-dark sea. There is an echo of Derek Walcott’s reading of his own twist on The Odyssey, titled Omeros, and Nikos Kazantzakis’ lyrical “sequel” to The Odyssey. There is the storm cloud of doom to this quest, a story that’s been told many times, and this perhaps could be the last.

Lee hopes these works will be widely shown and acquired by an institution. And one can imagine them sitting stoically on any number of august walls. But seeing them in Wimberley, in the afternoon breeze, when nature seem so pregnant with meaning only for the light to change… or else to see them on Instagram, through that damned frame we see everything from, always and forever distant, like catching the end of The Searchers from a different room. The swinging door between what could have been and what could never have been creaks closer to shutting, like the last rivulet poured from a vase until it dries, and leaves a faint memory that it once existed.