The ad in a 1911 issue of Billboard caught the eye of 14-year-old Vander Clyde* in Williamson County, Texas. Placed by the Alfaretta Sisters, “World Famous Aerial Queens,” the notice said the sisters were auditioning trapeze and high-wire performers in San Antonio. Inspired by attending circus performances, young Vander had been developing aerial skills on the family clothesline. Hired by the Alfarettas, he was costumed as a girl for dramatic appeal.

Jean Cocteau, Barbette, 1923. Carlton Lake Art Collection. © 1923 ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

A dozen years later, performing as “Barbette,” the Texan had become a Parisian sensation. Reviewing Vander Clyde’s performance in Nouvelle Revue Française, Jean Cocteau found his illusory allure “extraordinary,” and in 1930 Barbette appeared in Cocteau’s first film, Le Sang d’un Poete (Blood of a Poet). A portrait of Barbette in watercolor and pencil by Cocteau is included in the richly textured exhibition Vaudeville! at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

David H. Anderson, Annie Oakley, Little Sure Shot, 1886. Albumen silver print, 16.4 x 10.7 cm. Albert Davis / Circus Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

Some 200 vintage photographs, artifacts, and recordings from the Center’s expansive theater history collections bring into focus the amorphous, sprawling mega-genre of American entertainment called vaudeville. In addition to acrobatic and gender-bending acts like Barbette, the performance smorgasbord included comic bits and sketches, music, dancing, animal acts, ventriloquism, magic, early forms of moving pictures, and a crazy-quilt grab-bag of eccentric novelty acts. Will Rogers, represented in Vaudeville! by an image from his Ziegfeld Follies days, became a star by doing rope tricks and jawing about the news. Annie Oakley trick-shot her way from vaudeville stages to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

As noted in multiple sources, vaudeville’s beginnings are pegged at various times throughout the 19th century, and the all-inclusive medium continued into the 1930s. Vaudeville! explores the genre’s emergence from minstrelry, Punch and Judy, and other showbiz traditions. An 1846 broadside advertising the George C. Howard Family Company of thespians, kicked out of Providence, Rhode Island for opening a theater, recalls early America’s puritan streak that shunned the “professional liars” of performing arts. A facsimile of the 1822 oil painting, The Artist in His Museum, by the multi-tasking Charles Willson Peale, references the twin development of the theatrical arts and museums.

![Unidentified photographer, [Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and Sophie Tucker], ca. 1923. Gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Theater Biography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/20_300dpi-600x467.jpg?x88956)

Unidentified photographer, [Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Sophie Tucker], ca. 1923. Gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Theater Biography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

![Herbert Mitchell (American, 1898-1980), [Ethel Waters], 1931. Gelatin silver print, 35.5 x 27.8 cm. Theater Biography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/18_300dpi-397x620.jpg?x88956)

Herbert Mitchell (American, 1898-1980), [Ethel Waters], 1931. Gelatin silver print, 35.5 x 27.8 cm. Theater Biography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

![Unidentified photographer, [George Burns and Gracie Allen], ca. 1935. Gelatin silver print, 25.5 x 20.4 cm. Theater Biography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/22_300dpi-487x620.jpg?x88956)

Unidentified photographer, [George Burns and Gracie Allen], ca. 1935. Gelatin silver print, 25.5 x 20.4 cm. Theater Biography Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

![Unidentified photographer, [Yale Theatre in Austin, TX], ca. 1911. Gelatin silver print, 20.5 x 25.3 cm. Interstate Theater Collection, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/23_300dpi-600x484.jpg?x88956)

Unidentified photographer, [Yale Theatre in Austin, TX], ca. 1911. Gelatin silver print, 20.5 x 25.3 cm. Interstate Theater Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

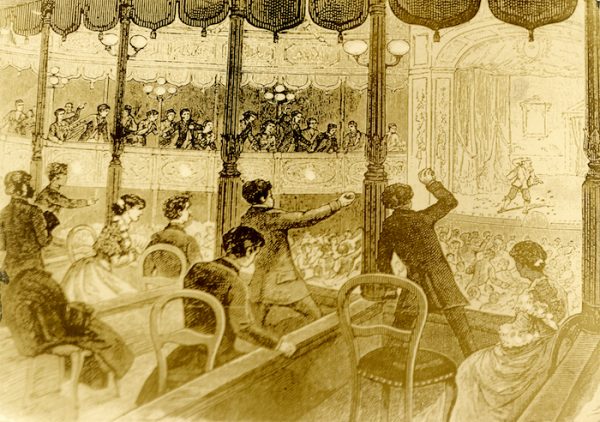

Audience throwing food at performers in Baldwin’s Theatre in San Francisco, ca. 1885. Albert Davis / American Theaters Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

A section in the exhibition titled “Will It Play in Peoria?” tours the vaudeville circuits that covered the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Chronicling the various moguls of the business and how they sanitized variety saloon fare (such as the shows presented at the Vaudeville, a saloon on San Antonio’s Main Plaza that hosted the famous killings of outlaws-turned-lawmen King Fisher and Ben Thompson in 1884) to appeal to the more civilized masses, Vaudeville! includes a 1925 gelatin silver print of the Majestic Theatre, a vaudeville house built in downtown Austin in 1915. The grand palace of entertainment survives today as the Paramount Theatre. A 1911 gelatin silver of Austin’s long-gone Yale Theatre, advertising a movie of the Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill western extravaganzas, represents the popular nickelodeons that presented short films that often featured vaudeville stars. Contracts, original letters, a list of performers behind on their agents’ payments, and other documents note the hard lives of many touring vaudeville artists. An 1885 illustration of the audience throwing food at performers in San Francisco indicates that theatergoers were not shy about critiquing a performance.

One of Harry Houdini’s ball weights with ankle cuff. Photo by Pete Smith. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

A nifty array of items from the Center’s extensive Harry Houdini Papers documents the famous magician’s vaudeville act. SEE the death-defying Houdini escaping from a straightjacket while hanging from a crane in Pittsburgh circa 1916! SEE the actual heavy ball and chain Houdini shed in miraculous escape feat after feat! SEE Houdini practicing his extraordinary and spectacular Water Torture Cell performance of 1914! Large color posters of his Vanishing Elephant Act and his Milk Can Escape Act hint at this unique performer’s appeal to the public.

![Unidentified photographer, [Ching Ling Foo], 1905. Halftone print, 13.8 x 9.3 cm. Magician's Collection, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/15_300dpi-547x620.jpg?x88956)

Unidentified photographer, [Ching Ling Foo], 1905. Halftone print, 13.8 x 9.3 cm. Magician’s Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

![Aimé Dupont (American, 1842-1900), [E. D. Davies and his ventriloquism puppets], ca. 1874. Albumen silver print, 16.5 x 11 cm. Messmore Kendall / Harry Houdini Papers, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/16_300dpi-1-415x620.jpg?x88956)

Aimé Dupont (American, 1842-1900), [E. D. Davies and his ventriloquism puppets], ca. 1874. Albumen silver print, 16.5 x 11 cm. Messmore Kendall / Harry Houdini Papers, Harry Ransom Center.

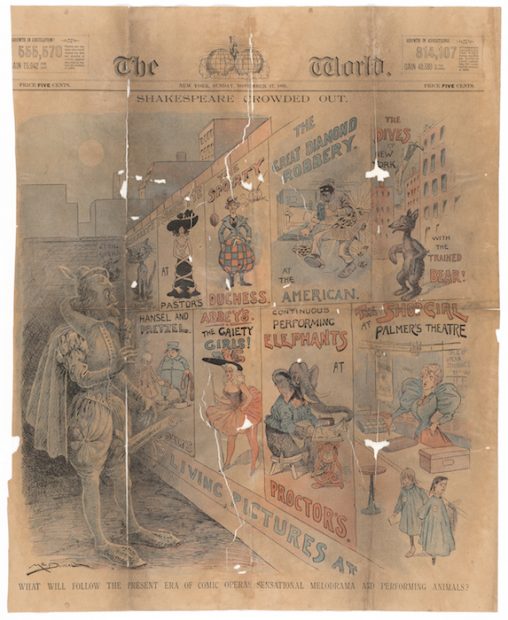

I’m a goner for cool vintage graphics and images, and Vaudeville! delivers such visualrifica in spades. A 1921 gelatin silver print of five or six year-old future jazz drummer great Buddy Rich as “Traps, the Drum Wonder” looks almost otherworldly. An 1874 albumen print of ventriloquist E. D. Davies with two of his large puppets looks even more so. And 1915 gelatin silver prints of vaudevillian Roy Arthur as a bizarrely clad Arabian dancer and as the vagrant clown Bunky Doodle indicate the versatility of many vaudeville performers. A facsimile enlargement of an 1895 editorial cartoon from the New York World lamented that Shakespeare had been “crowded out” in “the present era of comic opera, sensational melodrama, and performing animals.”

A 1928 gelatin silver print, The Marx Brothers as the Four Muskateers, reminds me of an oft-told tale about an important moment in the Bros’ vaudeville history that is said to have happened in Nacogdoches. Versions of the story set it in the 1900s or the 1910s. Touring as a noncomical musical ensemble called the Four Nightingales, the Marx Brothers played the local opera house. In the middle of the performance, audience members heard someone hollering in the street about a runaway mule. The audience streamed out of the theater to witness the rampage. When the audience members returned, an insulted Groucho began berating everyone present. Instead of taking offense, the Nacogdoches crowd roared with laughter. The comedy empire of the Marx Brothers was born, and Groucho was often heard to reprise one line from that memorable performance: “Nacogdoches is full of roaches.”

![Unidentified photographer, [Majestic Theatre in Austin, TX], ca. 1911. Gelatin silver print, 20.5 x 25.3 cm. Interstate Theater Collection, Harry Ransom Center.](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/24_300dpi-600x352.jpg?x88956)

Unidentified photographer, [Majestic Theatre in Austin, TX], ca. 1911. Gelatin silver print, 20.5 x 25.3 cm. Interstate Theater Collection, Harry Ransom Center.

Through July 15, 2018 at UT’s Harry Ransom Center, Austin

*Some sources have Vander Clyde’s full name as Vander Clyde Broadway. There are also discrepancies in his date of birth and the various stories of how he started performing dressed as a woman.