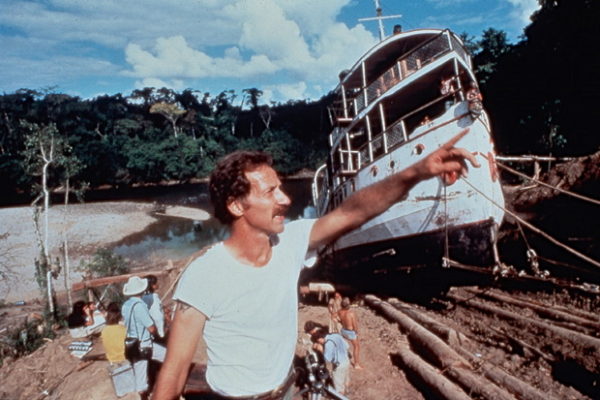

Herzog circa 1981

“Give me two years and some rope,” Werner Herzog teases the audience while planting the notion we too could hoist a ship over mountains like he did in Fitzcarraldo. Having once asserted, “It is never cash money that moves mountains, it is faith,” Herzog nevertheless thanked his sponsors.

His appearance at the opera house in Dallas in late August first seems to be some strange combination of a deal with AT&T for funding From One Second to the Next (his short film weighing the costs of texting and driving) and a promotion for the current theatrical run of his documentary Lo and Behold. But in person Herzog revealed he has no less than four films coming this fall, including his Netflix documentary Into the Inferno, and two feature films, Salt and Fire and the long-gestating Queen of the Desert. Taken all together, his output is a feat worthy of Winspear proportions.

Herzog at the Winspear in Dallas in late August

Over the course of the evening, Herzog’s late mentor and the author of The Haunted Screen, German film critic Lotte Eisner, loomed over the conversation. He has called her “the last mammoth”—pals with everyone from Fritz Lang to Buster Keaton, she legitimized Herzog’s own new wave of Bavarian filmmakers. In his memoir, Of Walking In Ice (which he claims to be better than all his films), Eisner is on her deathbed. Packing a bag and embarking in the cold of early December, on “one million steps in protest” from Munich to Paris, Herzog knew Eisner must be alive and well on his arrival. In his weariest moments, contemplating crossing the frigid Seine, Herzog recalls swimming fifty miles with a group of refugees who were fleeing from New Zealand to Australia, using only soccer balls to keep afloat: “I swam in front, being the only one who knew the route already.”

Balking at his reputation as an explorer (“a medieval construct,” he says), the filmmaker nonetheless recounted his adventures, the spoils of his bounty on view for suckers to ogle on the big screen. Herzog’s circus produces many wonders. Never a believer in film schools, Herzog once imagined his own version would train inductees in boxing, somersaults, card tricks and juggling. Today, his informal Rogue Film School watches Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the Apu Trilogy and counts the Warren Commission Report and the poems of Virgil as curriculum. Rumored also to teach lock picking and permit forgery, his guild counts this strange edict among its 12 commandments:

“Censorship will be enforced. There will be no talk of shamans, of yoga classes, nutritional values, herbal teas, discovering your Boundaries, and Inner Growth.”

Carving an idiosyncratic path through his oeuvre, Herzog screened clips that did most of the legwork in demonstrating his creative process. Notably debuting never-before-seen footage from his forthcoming Into The Inferno, along with a curiously strong presence from his 2009 Nicolas Cage crime-thriller Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call of New Orleans, Herzog enjoyed many ovations. But, the evening unfolded with few surprises for those versed in his lore. Mostly sticking to a script established in My Best Fiend; Fata Morgana’s famed interview commentary with Crispin Glover; Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams; and two of his own books, the interior of the man was glimpsed whose mystery perhaps functions best for those too busy to binge on his hefty back catalogue.

Maybe time is a flat circle. By sticking to his script, does Herzog not maintain a life-long held ethos? What was old becomes new again, with so much pleasure derived from hearing accounts directly from the voice you can’t believe you are actually hearing. The infamous bullshit postscript, starring those mutant albino crocodiles in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, proved no exception. Chalking up his last-minute trek to the biotope cupola housing the reptiles as nothing more than a hunch, his crew was able to capture haunting, but merely tangential, imagery. With no context discernable, Herzog decided to fabricate one:

“I want to take [the audience], at the end of the film, under my arm and drag them right into the kingdom of poetry and illumination.”

As the ridiculous clip plays out, audience laughter turns to tears as the power of Herzog’s metaphor sinks in:

“Nothing is real. Nothing is certain. It is hard to decide whether or not these creatures here are dividing into their own doppelgangers. And do they really meet? Or is it just their own imaginary mirror reflection? Are we today possibly the crocodiles who look back into an abyss of time when we see the paintings of Chauvet Cave?”

This meta experience astonished the crowd. In real time, the absurdity of Herzog’s faith in his idea gives way to seduction by its profundity. Still ecstatically proud of his work, he promises the audience, “You can expect that I’m gonna do these things as long as there’s breath in me. I will stop only if they carry me out in a straightjacket.”

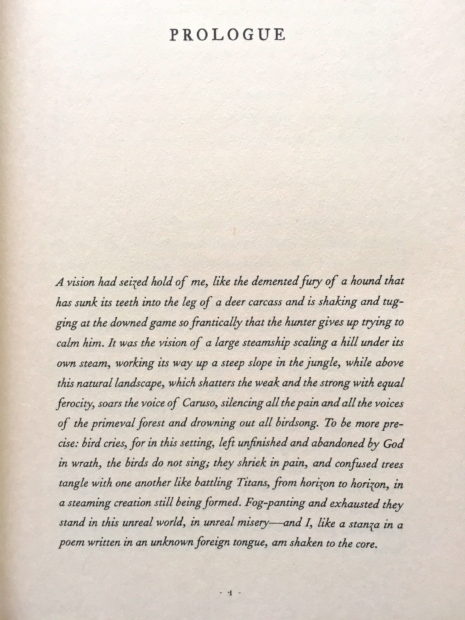

When attempting to explain himself and his life’s work, Herzog presents the prologue of Conquest of the Useless, his journal during the production of Fitzcarraldo. “It’s a vehemence,” he implores. “A vehemence of a vision that is coming at you. I cannot really describe it.” Opening up his book, he begins to read:

“A vision had seized hold of me, like the demented fury of a hound that has sunk its teeth into the leg of a deer carcass and is shaking and tugging at the downed game so frantically that the hunter gives up trying to calm him. It was the vision of a large steamship scaling a hill under its own steam, working its way up a steep slope in the jungle.”

Maggie Nelson’s recent The Art of Cruelty attempts to get at the creative power behind this zeal. She calls upon French poet Antonin Artaud’s 1930s manifesto, The Theater and Its Double to help define artistic cruelty, a similarly volatile impetus:

“From the start, Artaud was anxious to differentiate his concept of cruelty from that of simple sadism, violence, or bloodshed. His cruelty, he insisted, meant something quite different: “…the appetite for life, a cosmic rigor and implacable necessity, in the Gnostic sense of a living whirlwind that devours the darkness.”

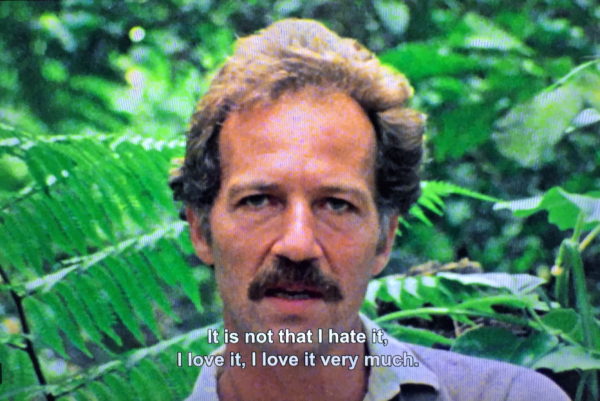

Artaud’s Nietzsche-ian insistence on cruelty was to extort, not hide, its evil nature. Perhaps, influenced by “the biggest pestilence on God’s wide earth”—über-diva Klaus Kinski—Herzog too embraces this fury as a means to triumph. In one of his more heroic monologues from My Best Fiend, Herzog, surrounded by dense foliage circa Fitzcarraldo, locates his combative ties with nature:

“Taking a look at what’s around, there is some sort of harmony. There is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. But when I say this, it is with admiration for the jungle. I do not hate it. I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment.”

Flipping to the ending of Conquest, Herzog reads its final passage, describing his complete lack of emotion upon seeing his ship crash down into the Rio Urabama, his bare feet bleeding, cut open by broken beer bottles. “All I grasped was a profound uselessness,” a vehemence utterly spent; the image not unlike that of an exhausted Kinski, haplessly drowning amongst the incoming waves at the end of Cobra Verde—their final collaboration.

Any discomfort or sadness felt by Herzog’s bragging about his Netflix volcano documentary getting simultaneous release in over 200 countries, when today’s movie-going climate has likely choked out Inferno’s chances of what would most deservedly include an IMAX run, is eased by Herzog’s own assertion that “the best functioning system of distribution for movies is still piracy.”

Ready to dismantle his pop-culture visage, he dismisses interludes with Joaquin Phoenix and Kanye West as mere “minutes of my life,” albeit reminding the audience he was once shot during a BBC interview by what he calls “an insignificant bullet.” Both frustrated and bemused, he grins:

“I do live on the internet in the form of imposters and doppelgangers and voice imitators. Facebook which is not me. Twitter which is not me. You name it. I do not feel uncomfortable with it. I keep saying it’s like my unpaid stooges. My unpaid bodyguards, they do combat out there.”

When asked about his approach to music, Herzog simply plays a second clip from Bad Lieutenant; a noisy shootout scored by the folksy harmonica of Sonny Terry’s Old Lost John where Nicolas Cage intones, “Shoot him again. His soul is still dancing.” Post-massacre, the camera pans from Cage and his goons to a break-dancing ghost and an iguana. Curiously, the same piece of music also scores the ending to Stroszek, one of the all-time-best dancing chicken non-sequiturs. Herzog could be trolling us, as he often similarly provides no clues as to what metaphors lay behind his dogmatic use of animals throughout his filmography. From Herzog on Herzog, here is one of his better insights:

“Look into the eyes of a chicken and you will see real stupidity. It is a kind of bottomless stupidity, a fiendish stupidity. They are the most horrifying, cannibalistic, and nightmarish creatures in this world.”