Text: Tami Kegley; photography: Page Graham

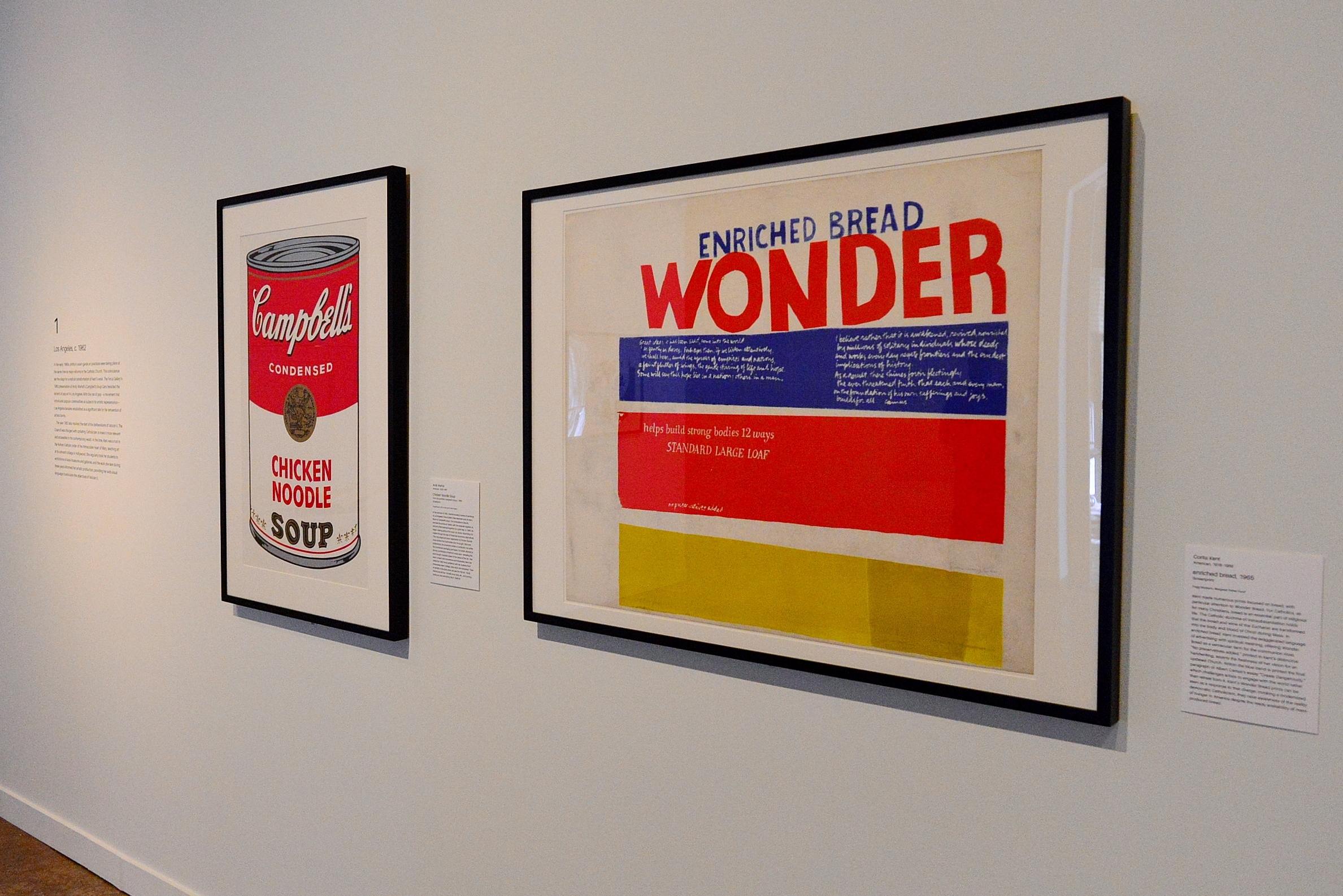

Warhol’s Chicken Noodle Soup alongside Kent’s enriched bread.

Corita Kent (1918-1986), also known as Sister Mary Corita, pursued the language of Pop Art in the Mad Men atmosphere of the 1960s. This exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Art focuses on the work that she produced between 1962 and 1969. It was a time rich with cultural collisions: the Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam War, Women’s Movement, the Vatican II Council.

Corita Kent and the Language of Pop, San Antonio Museum of Art, February 2016.

Combined with scripture, poetry and slogans, the Sister developed her own pop-art language that dovetailed her faith, activism and teaching with a message of acceptance and hope. At a time when the Roman Catholic Church was attempting to be more accessible, her works were the very soul of pop-culture accessibility. From 1936, she lived, studied and taught at the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles. She was the head of the college’s art department from 1964 until 1968, when she departed the order and moved to Boston.

Rarely seen screenprints from Roy Lichtenstein’s portfolio Ten Landscapes.

There have been exhibitions focusing solely on the work of Kent in the past, but most notable about this show is that it gives us the opportunity to view Kent’s work in context with her prominent contemporaries of the time. Much of the work has rarely been seen outside of the Corita Art Center. More than 60 of Kent’s prints are viewed alongside the works of pop art giants such as Robert Indiana, Jim Dine, Ed Ruscha, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Also brought into play are some of the other women working in this period, including Faith Ringgold and May Stevens.

Kent was aware of the work of her predominantly male peers, and they were aware of her. She had already been a recognized and influential teacher of the art of printmaking in Roman Catholic educational circles. Keep in mind, for example, that she was producing as an artist well before Warhol came onto the scene in 1962 with his first solo show of Campbell’s Soup cans at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. The work that Kent produced in this period wasn’t at all derivative, though she was clearly inspired by her contemporaries and the imagery of advertising art that surrounded her.

Anna Stothart touring the Cowden Gallery at San Antonio Museum of Art, flanked by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein

Anna Stothart, the curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at SA Museum, has done a great job of installing the show in the museum’s Cowden Gallery. The exhibition is laid out chronologically and it’s fascinating to see how Kent’s work developed. She became stronger and much more politically explosive as the 1960s unfolded. She grew angrier and more frustrated with the social injustice and the murders of such leaders as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968. In her own self-effacing words, “I am not brave enough to not pay my income tax and risk going to jail. But I can say rather freely what I want to say with my art.”

Katie Luber, director of the SA Museum, speculates about why Kent’s work was never broadly acknowledged, saying bluntly, “She was a nun and she was a woman.” She went on to say: “This show puts her into the context in which she belongs. If not presented in the company of Warhol, Ruscha, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein and Indiana, you would miss how subversive her work is. This show does it beautifully. She has this incredible visual appetite that you can see.”

Politically charged works by Corita Kent: (l-r) the cry that will be heard, ifi, love your brother, i’m glad i can feel pain – all created in 1969.

Chief Curator William Rudolph added, “We need a Corita Kent today. We have this show which I hope will resonate with people, but we need a Corita Kent to do what art can do, which is to use art to mirror society back to itself.”

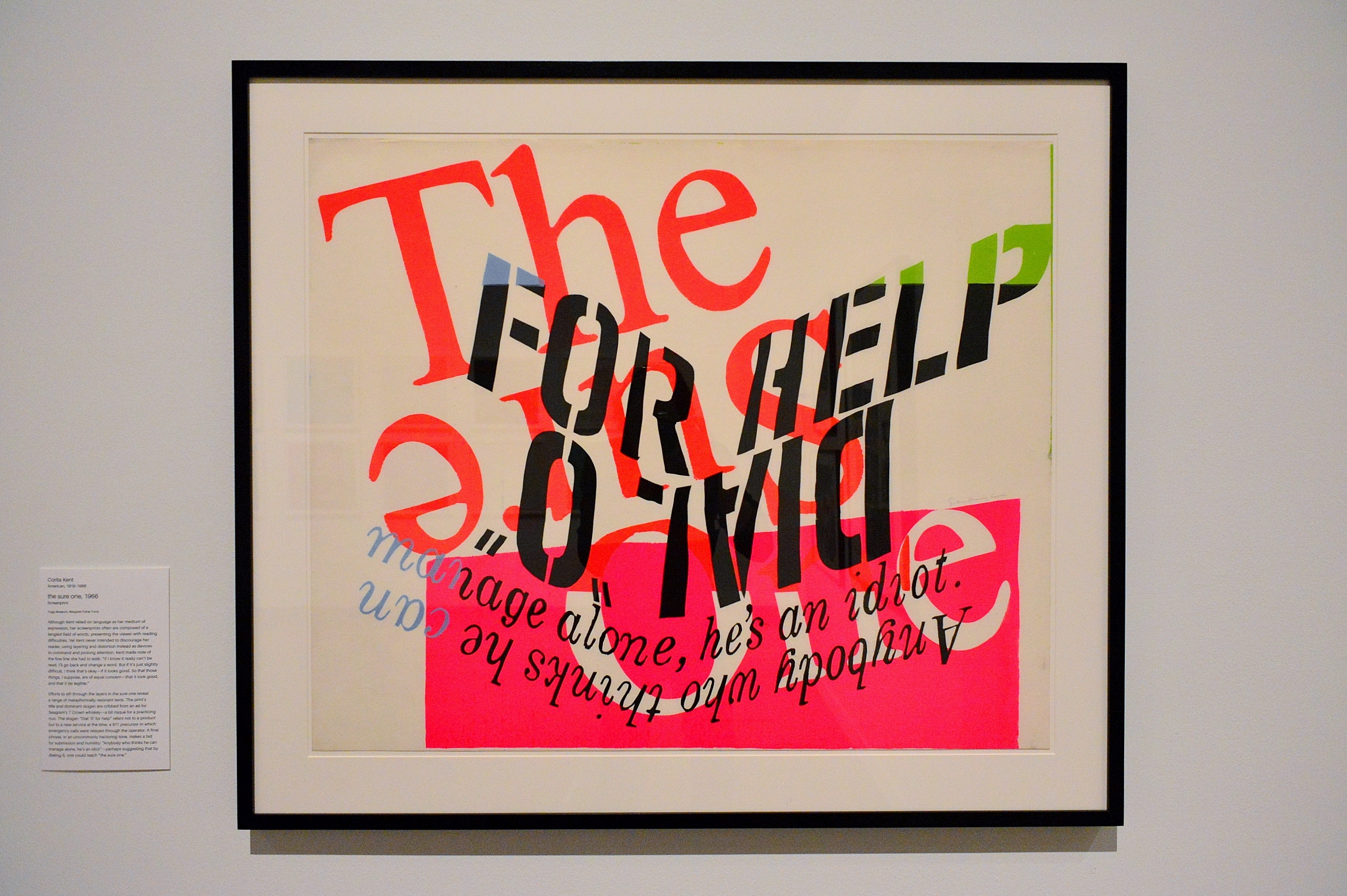

the sure one by Corita Kent.

Corita Kent and the Language of Pop is up at the San Antonio Museum of Art through May 8. The exhibition was organized by the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge; Susan Dackerman, the Consultative Curator there, was the organizing curator of the show. Due to the delicate nature of the work exhibited, this is the only touring date planned for it.

Boston Gas Tank (Rainbow Tank) by Corita Kent. In 1971 this public artwork was met with controversy. However, when the receptacle was replaced in the early ’90s the design was repainted due to “overwhelming requests for its return.”

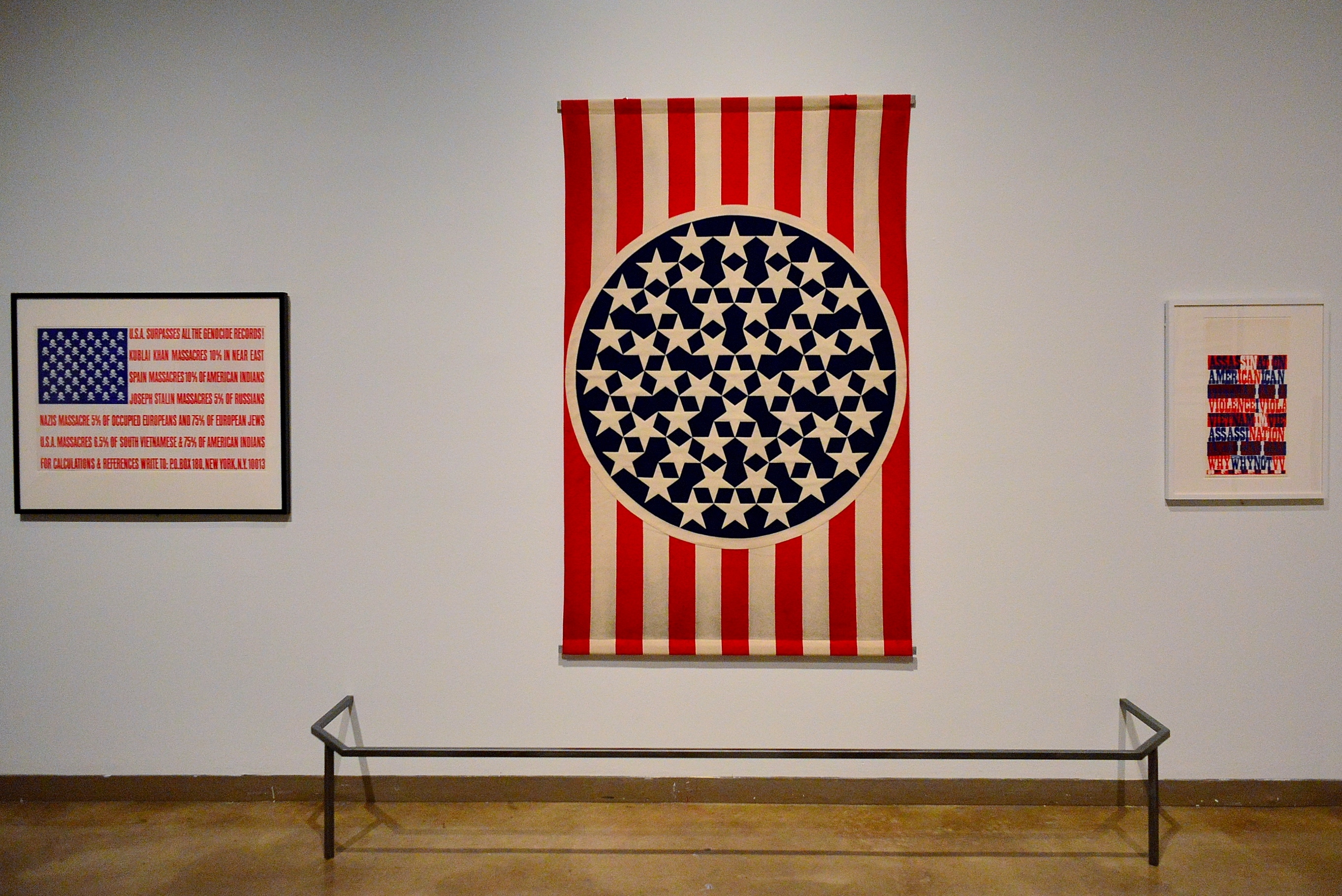

External Hexagon by Robert Indiana (c) flanked by two Corita Kent works power up (r) and handle with care (l).

By Roy Lichtenstein (clockwise) Paper Plate and Folded Hat shown with False Food Selection and Pear by Claes Oldenburg.

the juiciest tomato of all and song about the greatness (l-r) by Corita Kent. Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Tomato Juice Box (foreground)

news of the week, phil and dan, a passion for the possible (l-r) by Corita Kent

New Glory by Robert Indiana (c), USA Surpasses All Genocide Records by George Maciunas (l), American Sampler by Corita Kent (r).