Bring your dog to the South Florida Art Show and get a paw painting. Image found here.

Thirteen painting exhibitions are currently on view in Houston, in everything from major institutions (CAMH, The Menil, MFAH) to galleries (Moody, McMurtrey, Inman, Shelton, Art Palace, Borden, Butler, The Brandon) to non-profit spaces (Huckaby at Art League Houston). In general, the quality level is high, demonstrating the persistent malleability of the medium. Theoretically killed off many times over, it is one in which artists can still find a voice. I, personally, have never found painting to be dead, but I have sometimes found artists’ voices frustratingly submerged in a blender of stylistic trends and surface tricks, updating of old styles with new materials, and art historical references for the sake of art historical references.

Shake Hands With The Art Guys, 2013. Photo: Allison Hess. See Hess’ photo essay here.

My weekend seeing these painting shows coincided with a humorous but meaningful event at The Art Guys studio that cast all my outings in a different light. Over the past year, The Art Guys have performed 12 Events, one action per month. They walked the longest street in Houston, drove the 610-loop for 24 hours, signed their name for eight hours, shook hands with people in the Houston tunnels to celebrate National Handshake Day, repeatedly crossed the busiest intersection in the city for four hours, and so on. I did not see these works; many seem to be about locating yourself in the world in a simple way: whether walking, by car, as a citizen at City Hall, in public space, or an encounter with a stranger. Held unceremoniously in locations across the city, outside of any institutional support, many of these were probably missed by the art-going public.

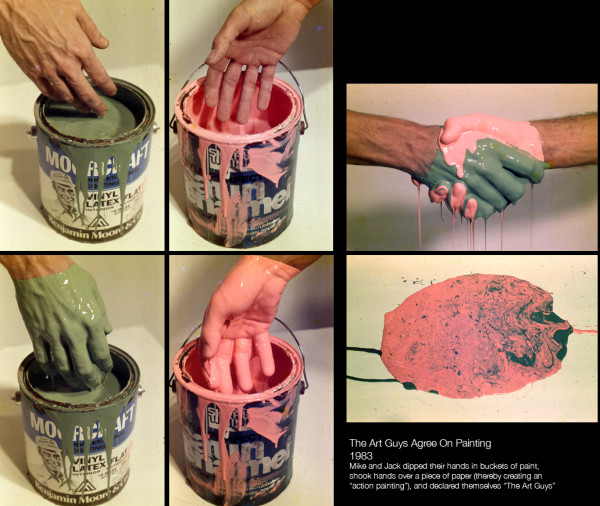

The final event, The Art Guys Agree On Painting, Again, This Time From Thirty Feet Up, alludes to the Art Guys’ origins. 30 years ago at the original Lawndale Art Center space (then a studio complex for graduate students at the University of Houston), Jack Massing approached Michael Galbreth and told him he wanted to do something. There was no audience and Galbreth did not even know what was going on. Massing presented Galbreth with a couple of cans of paint. They each dipped their hand in a respective can, shook hands, and Massing joked, “I guess we’re the art guys.”

According to Galbreth, at that time painting dominated the Houston art world conversation, with talk of Julian Schnabel, Eric Fischl, and neo-expressionism. Heroic authorship was valued over collaboration and art with humor was not taken seriously. The freshly coined “Art Guys” thought about the paint-covered handshake in this context and documented the action in the style of conceptual art. They made photographs of their paint-covered hands, as well as a photograph of the “action painting,” which was circumstantially created by the drips from their handshake on a piece of paper (which was discarded). The resulting photographs became not only a humorous stab at painting, but also pointed, as Galbreth puts it, to the “contrivance of conceptual art.”

In the thirty years since 1983, they have revisited the famous piece several times: in 1993 they made a black and white version, and again in 1995, for the cover of the catalogue Art Guys: Think Twice at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. For the 2013 reprise, The Art Guys staged what they called “an anti-elaborate pseudo-recreation” standing atop rickety 30-foot scaffolding, one foot for each year since 1983. Each carrying a paint can, they slowly ascended, one of them dipped his hand in yellow, the other in blue, and held a prolonged handshake as paint dripped three stories onto a sheet of paper. After the shake, they wiped their hands on their white coveralls, and everyone in the audience walked up to look at the splattered piece of paper.

They had “agreed” once again on painting, but what were they agreeing to? Was it an agreement that illustrates just how far to the periphery the act of painting was to their work? Or, more pejoratively, how far beneath them? Was it an agreement that something as simple as a handshake can have as much value as “high” art? Or am I overthinking? The best way to ruin a joke is by picking it apart.

I asked Galbreth about the Art Guys’ intentions in 1983 versus now. He brought up James Agee’s preamble of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men to refer to the terror of performance.

Agee wrote: “Beethoven said a thing as rash and noble as the best of his work. By my memory, he said: ‘He who understands my music can never know unhappiness again.’ I believe it. And I would be a liar and a coward and one of your safe world if I should fear to say the same words of my best perceptions, and of my best intention. Performance, in which the whole fate and terror rests, is another matter.”

Galbreth talked about art’s relationship to nature via John Cage (via Coomaraswamy): “Art is an imitation of nature in her manner of operation.” Also, before the actual performance, Galbreth casually referred in off-the-cuff remarks to Pollock’s famous statement, “I am nature.”

I got the sense that by asking Galbreth to talk with me about this performance, I was asking him to somehow talk about thirty years of work which the gestures bookend (but do not conclude). Even from thirty feet up and thirty years later, the title still harkens back to a time when painting was dogmatically debated, although the diversity and number of painting shows right now in Houston show painting resting in a state of peaceful (maybe overly content) pluralism.

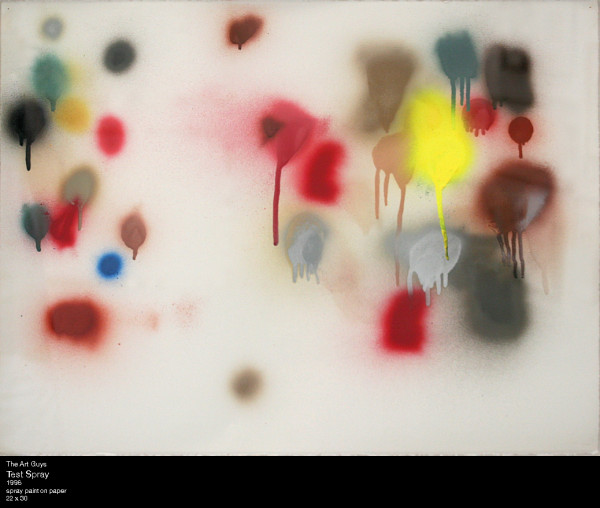

The Art Guys’ work, like that of Pollock and Cage, allows the uncontrollable world of chance, nature, and everyday life be the work. For example, The Art Guys created Test Spray (1996) as “a response/recognition/tribute to the spray paint markings found in hardware stores in the paint section from customers testing the color of spray paint. This human decision making, as regards to painting, seems as legitimate as any other.” Lending equal legitimacy to the intended and unintended borrows from the old Duchamp scenario that anything can be art, not everything is, and the artist directs or points.

But whatever we communally agree to call “art,” it is an intellectual category, crutch, and container that can often be extremely limiting. I went to The Art Guys’ performance with “painting” in my head, but after thinking more and speaking with Galbreth, locating it between the conventional poles of high/low, intentional/unintentional, object/idea seemed less and less interesting. In spite of their name, The Art Guys do not necessarily care if what they are making is art, yet my experience of doubt, disruption, and confusion confronting their action is what I associate with good art.

Nature, everyday experience, human relationships are disorderly, messy, and destructive. In a simple, lighthearted way, with a handshake thirty feet in the air and after thirty years, The Art Guys did not just agree on painting, but reaffirmed a relationship. It forces me to not just think about “art,” but life.

All this talk of nature and The Art Guys’ own insistence on mining the ordinary left me thinking of a passage from a short story in Lorrie’s Moore’s Birds of America:

Staring out through the windshield, off into the horizon, Abby began to think that all the beauty and ugliness and turbulence one found scattered through nature, one could also find in people themselves, all collected there, all together in a single place. No matter what terror or loveliness the earth could produce — winds, seas — a person could produce the same, lived with the same, live with all that mixed-up nature swirling inside, every bit. There was nothing as complex in the world — no flower or stone — as a single hello from a human being.

Perhaps a hello can just as easily be replaced with a handshake.