In 1971, Linda Nochlin famously asked "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" We know that her assumption is no longer true even though at the time her argument was correct. But what is the relationship between the identity of a woman as an artist and the content of her work in a post-feminist world?

This topic recently came up in a conversation with Lily Hanson in response to her show at Mountain View College. It continues with a link that exists between her work and that of Candace Briceño. Their use of soft humble materials like stitched felt with vague associations to craft and domesticity seems to allude to at least one definition of the feminine. Their work is certainly in contrast to large forms of steel, stone or bronze, with all of their traditional allusions to masculinity. But Hanson was quick to point out that she has no feminist statement to make with her work. What does it mean to have a feminist stance in one's work and what role does color or material play in this position?

Hanson's statement is in stark contrast to artists like Polly Apfelbaum who turned to soft materials and bright color as an overt rejection of minimalist machismo. But things have changed. Or have they?

Like Apfelbaum and Nochlin in the 1970's, art and its constellations of meaning has a symbiotic relationship to culture. So the key would be to understand how gender roles have changed over the past 30 years. More on that later.

Lily Hanson's show at Mountain View College is an installation that includes a series of semi-abstract forms. Immediately one senses playfulness in the work. The miniaturized scale and the pink and baby blue felt used to construct some of these forms, references childhood, or maybe cartoons. According to Hanson, an episode of The Simpsons was an inspiration for this piece.

As a counterpoint to the soft felt – wire and lumber are included as both material and image. All of the materials function as the thing in-and-of-itself. There is a minimal amount of craft, pointing more to choices of inclusion, exclusion and placement in the tradition of post-minimalist artists like Richard Tuttle. This adherence to the reality of both material and context subtly reaches toward illusion to the point that it is difficult to tell the difference between real and painted shadow.

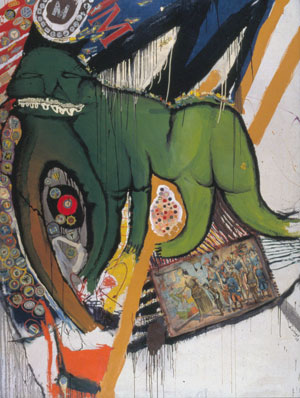

Another artist using felt and bright colors in Dallas right now is Candace M. Briceño at Mighty Fine Arts. This show includes paintings, drawings and sculpture. Her work is also included at the I-35 show at Dunn and Brown and the Dallas Contemporary in the traveling show, New Art in Austin: 22 To Watch.

Unlike Hanson, Briceño makes explicit images. Her 'grass islands' at both venues use felt and bright colors to construct pop-y still-lives of flowers. The Mighty Fine Arts show includes sculptures, paintings and drawings that intentionally blur the boundaries between media. Thread is used as a kind of sculpted line. In 'Lean' there is a subtle use of stitching as a pink drawn mark on a white field of felt.

The merging of painting into sculpture is more successful than its reverse. 'Pond' is a canvas where cotton duck and wool felt have not developed the same degree of resolution. Neither has the relationship between painted color and dyed color. Another misstep in the show is 'Pile' – a pile of felt bananas that doesn't do much more than a pile of bananas. On the other hand, two large drawings of bananas falling through the air are much more successful. Like the drawing to their right, 'Invisible' they carve out the white of the page with the grace and dexterity of Ellsworth Kelly and activate the space beyond its material fact.

What does the use of felt and bright colors do to the natural imagery that Briceno uses? How different would this work be if it were bronze? For one thing, the permanence of bronze would stand in direct contrast to the image of a flower, conjuring up ideas of mortality and other seriousness.

Candace Briceño also has an upcoming show at Women and Their Work in Austin, a venue explicitly dedicated to the promotion of women. It is the sex of a woman and not her gender that determines her eligibility. Both butch and femme may apply, using felt, textiles, bronze or steel. While this is a noble cause, I have spoken to some women who have a problem identifying themselves as "woman-artists."

Is the use of felt and bright color necessarily feminine? Once could say that the use of color separates this felt from that of Joseph Beuys or Robert Morris. In her artist statement, Briceño mentions her connection to fiber arts, which explores the use of textiles and fabric. When it began in the 1970's fiber arts was in cahoots with second wave feminism. But can third wave feminism help us to think of material or color and their relationship to gendered meaning in any other way?

Before dealing with what this might suggest we must first ask what effect third wave or even second wave feminism has had. The shape of this effect is oblique, it doesn't hold to a clear model of progress.

Like in many art schools, most of my students are women. But many of these women don't believe that there is any such thing as sexism or patriarchy. This is despite the fact that women still make less money than men in the US, that there still is a disparity of the number of women in politics and business. A recent New York Times article documented this trend for women who were CEO's, lawyers and doctors were leaving their careers in growing numbers. Jerry Saltz has been good about keeping the art world honest about these issues. In his review of this year's Whitney Biennial he pointed out that only 25% were women.

So what might third wave feminism tell us about Hanson or Briceño as artists? What might it tell us about their work? The third wave attempted to question traditional definitions of gender and sexuality through the use of critical theory. So, first of all, we might question the assumed relationship between authorship and the identity of the artist. In some sense culture plays a contributing role to the construction of meaning in these artists' work. As viewers we participate in this as much as they do. Secondly, we might question the necessarily link between softness, color, delicacy and nature with women.

I think that Lily Hanson comes closer to opening up these questions through her work. I can't help but think if the newfound success of Briceno's is due to the sacrine seduction of pretty flowers in bright colors made into cute cuddly stuffed toys. While I know that Candace Briceño places no explicit weight on a feminist statement there is an assumed value to 'nature' that Briceno holds that seems naïve and even a trap, especially if we remember its traditional association with women. On the other hand, Hanson's work is both soft and hard, natural and fake, large and small, exploding our assumption about our own place in this gendered world.

Images courtesy the artists.

Noah Simblist is an artist and writer who lives in Dallas and teaches at SMU.