When performers leave the stage artistry ends and memory commences.

Joseph Beuys ... Schlitten (Sled), 1969... Wooden sled, felt, straps, flashlight, fat, stamped in oil... 13 3/4 x 35 7/16 x 13 3/4 inches (35 x 90 x 35 cm)

Joseph Beuys was the ultimate personifying artist: the piercing stare he wore during his performances makes this abundantly clear. His ability to enlarge the activities of an eventful life goes beyond all the bounds of method acting and approaches that most un-modern of artistic attributes: shamanism. But Beuys also made objects, translating the intensity of his performance into art by making sculptures and installations at a furious pace. Beuys’ practice allowed him to create the stage set, act in front of it, and then distill the event into a sculptural artifact.

If Beuys the performer was a man on fire, full of intensity and fervor, his pose as a sculptor was one of strategic indifference. Craft in his public pieces (but not in his works on paper and smaller objects) is almost always perfunctory and often archaic, incorporating materials and processes that defy the formal vocabulary so essential to modern art. Beuys died in 1986, and now that he has left the stage the artifacts he created project an oddly sepulchral feeling, and understanding this work without some knowledge of the artist’s life history can be a difficult task.

Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, and Environments, co-organized by the Menil Collection and the Tate Modern, provides American audiences the first posthumous revaluing of the public output of this most influential post-war artist since the 1993 MoMA survey of his drawings. It is the public side of Beuys that is on display here (those interested in Beuys’ abundant, very beautiful small objects and works on paper are advised to make the pilgrimage to the Museum Schloss Moyland in Bedburg-Hau, Germany). Actions, Vitrines, and Environments is a partial portrait of a pivotal artist — imagine trying to understand Beuys’ American doppelganger, Andy Warhol, after only viewing a selection of Marylins, Elvises, and Car Crash paintings. But half a loaf is better than none, and this show provides viewers with plenty to chew on.

While not evangelical in the religious sense, Beuys can be truly said to have been “born again” after his Stuka dive-bomber was shot down on the Crimean Front in 1944. His copilot was killed; but although grievously injured, Beuys survived after being rescued by a nomadic band of Tartar tribesmen. “I remember voices saying ‘voda’ (water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat, and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep the warmth in.” This imaginative remembering (he was largely unconscious) grew into a personal myth that became a way of starting over after the wreckage of World War II began to clear.

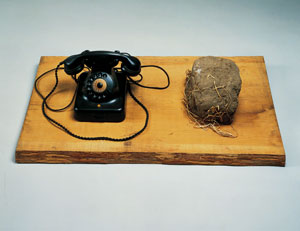

Joseph Beuys... Erdtelephon (Earth Telephone), 1968-71... Telephone, earth, straw, glass and wood... 7 7/8 x 30 x 19 1/4 inches (20 x 76 x 49 cm)

Throughout his life, Beuys enlarged on his experiences in this fashion, spinning personal events into societal talismans that advocate change as much or more than aesthetic value. Obsessed with attaining a mythic reconciliation between science and nature, his art manages to be strikingly post-modern, strangely pre-modern, and officially at odds with the bulk of the 20th century modernist canon. Throughout, his art evokes the words of his major artistic influence, German sculptor Wilhelm Lehmbruck: “Every work of art must carry with it a trace of the first days of creation — the smell of the earth, one might say. Something animal.”

Beuys’ work negotiates the intersection of social/private, individual/group polarities, using objects from life and simple leitmotifs culled from personal experience — the fat and felt attached to his Sled (1969), for example — as the basic building blocks of a personal liturgy. Derived as much from medieval communitarianism as from contemporary social issues, it seeks to square the circle between science and nature, Christian and pagan, the individual need and the collective good. This is a striking irony, for while nearly all of his work shuns the raw materials and processes of high art, one of his major innovations — the vitrines that are a substantial component of this show — emulate in their attitudes of display and valuation one of the major innovations of the modern era: the museum.

Most notable in this regard is Sweeping Up (1972/85), which ”documents” a performance Beuys gave at the Düsseldorf Academy in 1972. All the attributes of the actor are present, minus the act: broom, ample miscellaneous garbage, and didactic pamphlets Beuys printed on plastic bags. The centerpiece of Untitled II (1956/75) is a symbolic creation, Spade With Two Handles (1964), which Beuys utilized as a prop in a 1965 Fluxus event. Here he juxtaposed it with other works to create a mini-archive: a drawing, the small bronze Bridges of Understanding (1956), a pitcher and basin and his iconic Felt Suit (1971). These totemic relics refute formal analysis, except for the unity they gain from cohabiting within a neutral space. And this seems to have been Beuys’ intent — to disassociate the hierarchies of craft and construction from symbolic expressions that are at once deeply personal and strongly public.

The environments enlarge the controlled space of the vitrines by claiming entire museum galleries as their frame, and Beuys was not shy about expanding the scope and scale of his environments to fill and eventually spill outside of the museum in activist events like his symbolic tree-planting, 7,000 Oaks. Four environments are included in this exhibition, which does not sound like much in terms of numbers, but which is quite substantial if you measure it in gallery real estate, since every installation requires its own room. All were made within the last ten years of the artist’s life: Tram Stop (1976), Economic Values (1980), Terremoto (Earthquake) 1981, and The End of the Twentieth Century (1983-85).

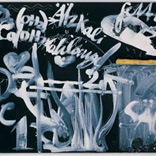

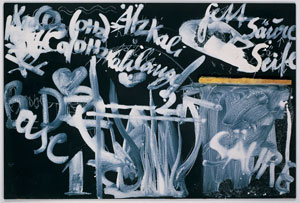

Joseph Beuys... Jungfrau (Virgin), 1979... Chalk, tempera, wood, soap, blackboard... 33 1/16 x 49 5/16 inches (84.2 x 125.3 cm)

Writing in the exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern curator Sean Rainbird talks about the difficulty of accurately recreating these works after the artist’s death, since “Beuys treated his exhibitions as flexible propositions, and treated each opportunity to exhibit his work as a dynamic interaction between artist, object, and space.” So a work like the (mostly) cast iron Tram Stop will appear completely different in archival photos than it does at the Menil, and a work like Economic Values, which Beuys installed at the Stedelijk Museum with historical paintings from that museum’s collection, is here surrounded by 17-century Dutch and Flemish works from the Menil’s own holdings. The fluidity of presentation that Beuys allowed has become a commonplace in the art world, but it does make you wonder: how will this translate in 100 years, after the artist’s drawings for The End of the Twentieth Century have been lost to flood or war? In the meantime, the work itself stands serene and self-sufficient, stonily denying the mutability of historical intervention.

I view filmic records of artist performances with a skeptical, media-saturated eye. Early video performances were often so much about process (think Bruce Nauman) and so technically primitive that they can now seem deadeningly long and self-indulgent. That said, do not forgo the 6 “action films” included in this exhibition. Here you will encounter Beuys’ eerie stage persona (How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, 1965), the solemn rituals he built into everyday actions (Brown Cross/Fat Corners/Model Fat Corners, 1964), and the mythmaking that has made him one of the lasting influences of the second half of the twentieth century (I like America and America Likes Me, 1974).

Eventually the straw in the vitrines will turn to dust. The fat will rot, and the many small bones will calcify. Objects that are now clearly understood will become cryptic runes for future audiences. In the meantime I am very glad to have had the chance to reacquaint myself with the outsized persona of Joseph Beuys. I almost feel like I know him, and I find myself saying to myself: Not bad for a youthful circus runaway; not bad for a student of natural sciences and Lehmbruck; not bad for a shot-down, nearly dead Stuka pilot; not bad for an influential, agitating professor; not bad for failed Green party candidate and planter of 7,000 oaks. Not bad indeed.

Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments remains on view at the Menil Collection, Houston, through January 2, 2005. A slightly different version of the show travels to the Tate Modern, London, February 4- May 2, 2005. The well-illustrated exhibition catalogue features essays by Mark Rosenthal and Sean Rainbird and a chronology by Claudia Schmuckli.

Images courtesy the Menil Collection.

Christopher French is a writer and artist living in Houston.