One of the most satisfying aspects of When 1 is 2: the Art of Alighiero e Boetti is the sheer diversity of the work. While the divergent paths of Boetti’s explorations ultimately reveal their common origins, at first glance the exhibition reads like a group show.

Untitled”- Victoria Boogie Woogie, 1972, (detail) …5,042 envelopes and 35, 280 stamps 42 panels,…61.75″ x 37.4″ each …Collection Gian Enzo Sperone, New York

Even in individual pieces the visual experience is so rich our eyes can hardly take it all in. Like a wide-eyed child possessing the wisdom of years, Boetti is playful, curious, and creative; his refusal to adopt a signature style is so refreshing that we might find ourselves wondering why these traits seem rare in contemporary art.

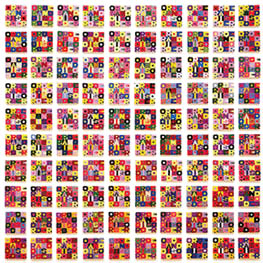

Many were invited to come play at Boetti’s house, and collaboration informs much of his work. Reaching beyond the traditional engagement of craftspeople or studio assistants, he allowed the chance and serendipity of his collaborators” participation to decide the ultimate form of his ideas. In Alternating One to One Hundred and Vice Versa, Boetti defined the parameters for a series of 50 kilims (tribal flat-weave rugs), but relied on friends and strangers to come up with the designs. In the Biro ballpoint pen series, Boetti and his friends created monochromatic mosaics of individual pen strokes. To these beautiful, systemic abstractions Boetti then added layers of meaning with words and writing systems he’d invented. But it is the blue, red, green, and black surface of works like The Six Senses and Ononimo where the collaborative investment pays off with extraordinary chromatic variety produced by each hand’s application. In his most well known collaborations, Boetti provided Afghani craftswomen with the design and guidelines for his embroideries, but left decisions such as color choice and juxtaposition to the embroiderers.1 The installation of one of these pieces — Order and Disorder — even requires the collaboration of those installing it, as Boetti’s instructions call for the random distribution of the 99 squares in the Disorder portion of the piece. At times Boetti even collaborated with himself, writing with his left and right hands simultaneously, as he did in several performances and in the To Oneself series. In the photograph titled Twins, the artist stands hand-in-hand with himself. This piece coincided with the addition of “e” (and) to his name, forever acknowledging the collaborative essence of much of his work.

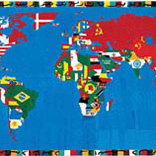

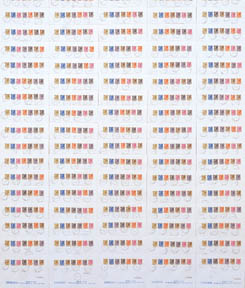

Boetti’s approach to the many projects he undertook was open-ended. In contrast to a discrete body of work, he would revisit themes and strategies throughout his career, finding tremendous variety within repetition. While the postal projects in this exhibition all date from the 1970s, Boetti’s “collaborations” with the postal service were not limited to that decade. The Map embroideries that began following his first visit to Afghanistan in 1971 were redesigned every few years, each iteration literally mapping the geo-political ebb and flow of national boundaries. The Cover series originated from pencil drawings like Broken Neck Long Arms (1976) that featured a grid of doodles and traced magazine covers. By the eighties, the doodles were gone and the grid became an annual chronicle of world events, fashion trends, and international celebrities. As the Italian critic Giovan Battista Salerno has discussed, many of these series are infinitely extensible:2 an annual installment of Cover for each passing year, an ongoing inventory of the world of people and things in further renditions of Everything, or updated Maps and catalogs of The Thousand Longest Rivers in the World that track the vicissitudes of man and nature.

Boetti was fascinated by the building blocks of our world, particularly those that are taken for granted: alphabets, numbers, calendars, maps, infrastructures, and systems of categorization. He wondered what is lost when these things are overlooked in favor of their underlining meanings.3 He questioned how reliable they are in fulfilling their alleged functions. He asked what creative possibilities they yet hold, the new meanings and systems they might offer when re-combined in new ways.

Order and Disorder (Block 1), 1985-86 …Embroidery on fabric on wooden frame …199 parts, 61″ x 61″ inches each…Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

He liked the fact that these building blocks already existed, fully formed. Of the Map series, Boetti wrote: “I did nothing for this work, chose nothing myself, in the sense that: the world is shaped as it is, I did not draw it; the flags are what they are, I did not design them.”4 A similar approach formed the basis of Twelve Shapes Starting From June “67, in which Boetti used only the shape of countries or regions from the headlines of his daily newspaper over a period of four years. In the case of the postal works, the system, its rules, and its instruments were already in place. For Untitled – Victoria Boogie Woogie Boetti’s decisions were limited to the permutations of stamp placement; for Postal Dossier, the intended route of the non-existent addressee was the principle avenue of exploration.

In the many embroideries that incorporate his own language or that of his collaborators, writing conventions were dispensed with and “meaning” is conveyed only to those also willing to dispense with their expectations: text must be read from top to bottom not left to right; it is multi-colored or alternates from black on white to white on black; one block of text is embedded in another; Italian abuts Farsi, (two languages, one imagines, in which few people can claim mutual fluency); and overall composition and color tempt the eye away from bothering to discern any meaning at all. We’re left looking at the alphabets instead of reading them.

In the Cover series, Boetti inverts the strategy he used in the text embroideries, this time muting the visual cacophony of the newsstand experience by draining it of color. The black and white replicas of magazine covers deny the competitive edge that publishers vie for with eye-catching photography. With each cover now displayed on equal terms, we discover just how strange the juxtapositions of imagery have become in print (not to mention televised) media. Film stars and fashion models in various states of provocation cavort amongst soldiers, terrorists, unemployed Europeans, and heads of state — horror and leisure, celebrity and infamy, luxury and travesty all in one endless tableau. What meaning can be discerned from such contradictory conditions?

And so without accusation, Boetti quietly questions notions of meaning or absolutes accepted without consideration. What happens to meaning when the building blocks used to construct it are themselves indecipherable? What do borders mean when most can hardly identify any of the countries and regions? How can something as seemingly straightforward as cataloging the world’s longest rivers help us better understand our planet when the system of classification applied (in this case length) is entirely undependable and at times even arbitrary?5 And what meaning can a world of infinite choice, endless variety, and the all-at-once sensibility of Western culture possibly offer? The two embroideries titled Everything, which initially suggest the fun of puzzles or Colorforms, are soon a disorienting experience. We are quickly overwhelmed by our attempts to tease out the individual forms and retreat to a safe distance from which we can appreciate the overall design instead.

In spite of these questions, the work does not leave the impression that Boetti is practicing some form of institutional critique. His questions are not rhetorical; he doesn’t point fingers and he doesn’t claim to have answers. Instead, his approach is more like that of a child seeing the world for the first time, wondering how things work, why they work the way they do, and how he can play with them. Though we may find hints of his sympathies, we see little in the way of a political or social agenda, and never at the expense of his aesthetic program. While the occasional wink is in evidence, Boetti’s stance is not ironic. Curiosity and wonder sustain Boetti, not the need to make a statement or to stand aloof.

And it is this curiosity and wonder along with Boetti’s imagination and playfulness that are the enduring impressions of When 1 is 2. Two works in particular embody these aspects of his art. The first is the large, blue version of Airplanes, an encyclopedic whirlwind of private, commercial, and military aircraft. It’s as though Boetti were fulfilling some childhood dream of covering the ceiling of his bedroom with every model airplane his local hobby shop carried. The second is one of his last works, the bronze Self-Portrait. In it, the life-size figure of Boetti stands atop a pile of river stones, a hose in one hand. From the hose a stream of water arcs onto his head, and from his head steam rises. It’s not the melodrama of stovetop sizzle, just the near invisible mist of an inquisitive mind.

1. Morsiani, Paola, “Alighiero e Boetti: Halving a Double”, When 1 is 2: The Art of Alighiero e Boetti, Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2002, p. 29-30.

2. Salerno, Giovan Battista, “Alighiero e Boetti”, Parkett, no. 24, p. 46.

3. Appiah, K. Anthony, ‘script Reading”, Worlds Envisioned: Alighiero e Boetti and Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Dia Center for the Arts, New York, 1995, p. 19.

4. Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn, “Alighiero Boetti: Artist’s Statement [1974]”, Arte Povera, Phaidon Press Limited, London, 1999, p.237.

5. For more information, see Anne-Marie Sauzeau Boetti’s “Introduction” from Classifying the Thousand Longest Rivers in the World, 1977, reprinted in Christov-Bakargiev, p. 239.

Chris Ballou is a writer, curator, and KTRU DJ working in Houston.