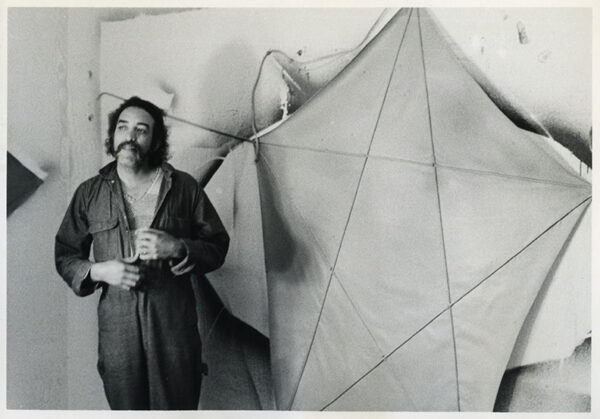

Joe Overstreet with his “Flight Patterns,” 1972. Courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Hickey – Robertson, Houston

Taking Flight, the solo exhibition of the works by the abstract expressionist Joe Overstreet, currently on view at the Menil Collection, opens up a magnificent and much-needed conduit of conversation about the artist, his work, and the movements and politics of the different time periods during which he made his art. Like Overstreet, many visionary artists active during the 1960s and 70s either worked across artistic disciplines or were wholly invested in and nourished by the intersection of disciplines. The visual artists were fueled by the music and poetry of the time. The alternative gallery and performance spaces, like Overstreet’s Kenkelba House, also presented dance and performance art. Visual artist Moki Cherry was extending the scenic backdrop to cover the stage floor, and her designs included clothes that her husband, the renowned trumpeter and composer Don Cherry, and his bandmates would wear in performance and everyday life. Sun Ra exploded on the scene with wild music accompanied by dancers and his own cosmic technicolor performances. John Coltrane gave us music of an artistry and spirituality so powerful that it became sacred music to many, displacing forms of what might be called traditional religious music for something completely nondenominational and abstract.

It is fitting that we celebrate Overstreet, who broke open his stretchers to allow his canvases to abandon the square and rectangular forms in the 1960s. He eventually sent his glorious paintings soaring into the air with his flight patterns of the 1970s. As an artist, he reached us with a deep and subliminal dialogue. Some of his early paintings are a tribute to renowned musicians like the jazz pianist Horace Silver and the band leader Sun Ra. To continue the conversation across time and artistic disciplines, I asked the saxophonist and composer James Brandon Lewis, who was in Houston being presented in performance by Nameless Sound, and trumpeter and composer Tim Hagans, to talk about their impressions of the Overstreet exhibition and how they relate his work and the power of abstraction in visual art to music.

Lewis and Hagans are two musicians well-versed and connected to the history of jazz, yet both have developed their own unique creative voices on their instruments and compositions. The Guardian describes Lewis as “one of the fiercest sounds in jazz today” with a “penchant for unbound exploration.” He is informed by the rhythms and textures of hip-hop and funk while remaining rooted in jazz. A recipient of the JazzTimes Album of the Year designation and recently named Downbeat’s Artist of the Year and Composer of the Year, Lewis has released 16 albums and maintains an active touring schedule with the James Brandon Lewis Trio. Hagans has been nominated for GRAMMYS for Best Instrumental Composition and Best Contemporary Jazz CD for his recordings for Blue Note Records. He has performed with his quartet and quintet ensembles at Jazz at Lincoln Center, Birdland, the Brooklyn Museum, Smalls Jazz Club, and many international festivals. His most recent CD, A Conversation, an all new, original multi-movement concerto performed by Hagans and the Hamburg Radio Jazz Orchestra, was the June 2021 Editor’s Pick in DownBeat. Hagans has also performed with Dexter Gordon, Joe Lovano, Dave Liebman, and Thad Jones, who encouraged him to begin composing.

I have divided the conversation into the galleries where it took place.

Outside The Galleries:

We began in the hallway just outside the exhibition galleries, standing in front of Overstreet’s monumental Justice, Faith, Hope & Peace, painted just after the assassination of Martin Luther King.

James Brandon Lewis (JBL): It is interesting that Justice and Peace are bookended and have the same shape, as if they are conversing with each other. You have Faith and Hope in the middle. It is this whole idea of a circle of unity, of completion. I think that we should be embodying what he is saying right here, that justice, faith, hope, and peace are in conversation with each other. They are in communication. The 1960s were such a turbulent time. What can bridge the gap: faith and hope, and he places them right in the middle. This is something to think about.

Right now, there is an exhibit of Jack Whitten at the MoMA. Overstreet and Whitten were friends; they were contemporaries. This idea of abstraction is funny to me because, essentially, music to the average citizen is abstract. You take the sheet music away; those are assigned values similar to these paintings. Overstreet has assigned meanings through titles. Someone could easily look at this work and say, “Well, what does he mean by this?” But you have to respect that, just like musicians, visual artists assign meaning to things. This is what artists like Overstreet and Whitten have in common: this ability, as Whitten would say, to “structure feelings.” This is the same thing that musicians are doing: we are embodying, we are giving meaning to sound essentially, and sound is something that you can’t touch or taste, or see really, without notating it. As musicians, our musical notation is our attempt, like what Overstreet is doing, to structure our feelings.

Michele Brangwen (MB): There is such power in his use of colors. Tim, you have synesthesia, and you have written music about the idea of hope. Could you talk about the relationship of color to these ideas? Hope is orange, blue, and peach. What color sensation comes to you with the idea of hope?

Tim Hagans (TH): I have synesthesia, so when I think of ideas and emotions, letters and numbers, musical notes, I see colors that go with them. For me, hope is green. Elvin (Jones, the legendary drummer in the classic John Coltrane quartet) had it. There is a video on YouTube where he talks about it. When you have synesthesia, your colors are consistent within your associations, but the specific colors differ for different people. I wrote a multiple-movement work called In The Key Of Synesthesia for the Hamburg Radio Jazz Orchestra using all the musical elements of the ensemble plus some orchestral percussion. I tried to use all sorts of instrumentation to describe the colors I see. One of the movements was about the idea of returning to hope, and when we were rehearsing that movement, the saxophonist Luigi Grasso, who also has synesthesia, had a solo. I kept telling all the musicians — they don’t have synesthesia — think green. He jokingly said, “I can’t play this solo you wrote for me because it is the wrong color. For me, hope is brown. Is it okay if I think brown?”

MB: Did your synesthesia interfere with your perception of the Overstreet canvas, Hope?

TH: Looking at the spiral in the center and how it meets and reverses itself, it feels like hope. All four canvases very much feel like their titles. I can’t explain it in words, but they all seem to embody their titles. I felt the same way as you did, James, that the colors and shapes were in conversation with each other.

JBL: When we use the term abstraction, it makes it sound otherworldly, but really, it is to be creative and to put something into being. When we look at these paintings, we are looking at someone’s attempt to get what is inside of them outside of them, or you could say to bring us into them. Sometimes these terminologies are kind of confusing. The work is getting away from the figurative and realistic, moving away from the whole idea of life drawing and getting into shapes and different things that actually exist in the environment. We can find all these shapes in the natural environment so what is necessarily abstract about it, except that we place it in that category.

It is the same way with music. When you think of Sun Ra, for instance, his band is an example of people communicating their interpretation of existence. Who are we to say what that existence is for anyone? To someone who might be used to hearing Sun Ra or seeing these paintings by Overstreet, this could be normal, natural, somebody’s lived experience.

MB: In my own artistic practice in contemporary dance and music, nothing is literal about what we do. In rehearsal, we talk a lot about the internal narrative, and maybe there are some movements or music that you can assign something specific. Still, it is so much better when that is not conveyed to the audience, and that is just open to interpretation.

JBL: Literal and nonliteral have a lot to do with who is allowed to control the narrative. I reflect on the impressionist composers, like Debussy, for instance. The whole assumption is that you can see waterfalls in your mind, and that is respected. If Sun Ra says he is from Saturn, that should be respected, too.

MB: Whether it is painting, music, or dance, the art form is a conduit to a greater universe that is out there. The artist is the vessel conveying that. For me, what is important is whether the channel is open or not. And when it is open.

JBL: Exactly, and when it is open, you have an understanding. Art is a way for us to understand complex things, like mnemonic devices designed to trigger things. This is like a mnemonic device, and music has them: when we learn “Every Good Boy Does Fine,” it triggers us to know our five lines and four spaces.

I am happy his exhibition is going on, and I think about his predecessor, Norman Lewis, whom I am also very interested in. He was an abstract expressionist in the same age range as Jackson Pollock and Romare Bearden. Ed Clark, Whitten, and Overstreet were a generation later, but they are definitely in conversation with their predecessors.

MB: Yes, and we are three people standing in front of this work having a conversation, but we are also having a conversation with Overstreet, so it reaches across time. It makes you feel like there is no time.

JBL: Exactly. It is the same thing with music. Time is relative. I just think about that period on the Lower East Side in New York. In the 60s and 70s, these guys were really making it happen at all costs. What Overstreet and Whitten were trying to express was this idea of: “No, no, no, we are allowed to assign meaning and feeling. We also feel.” — which is very fitting for the time period. We can have a conversation and don’t have to be limited. I was reading an essay by Norman Lewis recently, and it was this understanding that Blackness isn’t myopic; you don’t always have to comment. We don’t have to live only within our cultural understanding; we can also have the full scope and expansiveness. There was a different vibe with these folks; they were trying to be seen in a way that was like, “Give me the whole conversation, give me the whole thing.

The Senegal Series Gallery:

Instead of following the course of the exhibition, after a brief discussion in the first gallery, both James and Tim headed straight for the last gallery, where the Senegal series hangs.

JBL: These are my favorites. I was in here yesterday. I really like these.

TH: Me too. These are just incredible.

JBL: There is just a certain energy. I don’t know if it is the colors that make you feel that you are just alive. I think the value of art is the way in which it makes you feel. Sometimes we try to make feelings passé, because we are all about technique, technique, technique. But then it is like it was last night [referencing Cecile McLorin Salvant’s salon vocal performance in the Menil’s lobby, presented by the Menil and DACAMERA], alright, this is amazing. Once she got to that blues, everybody was like, “Oh yeah! It still does it!”

TH: Yeah! It’s that fourth bar in the blues.

JBL: Exactly. It still does it. It is because there is something human about it. It is the same thing with this art. There is something human about it.

TH: I had read a little about Overstreet but not much about this individual series. When I saw these for the first time, I didn’t really know the specific story behind each painting or even the story behind the dimensions of the canvas. That’s how I like to absorb art. I don’t want to know what a movie is about. It is about this, just tell me in three words. That is all I need to know. And if I read a book by an author where someone told me I should read this, I don’t read what it’s about. I just want to start on page one. So when we came in here…

JBL: You were just fully immersed in it.

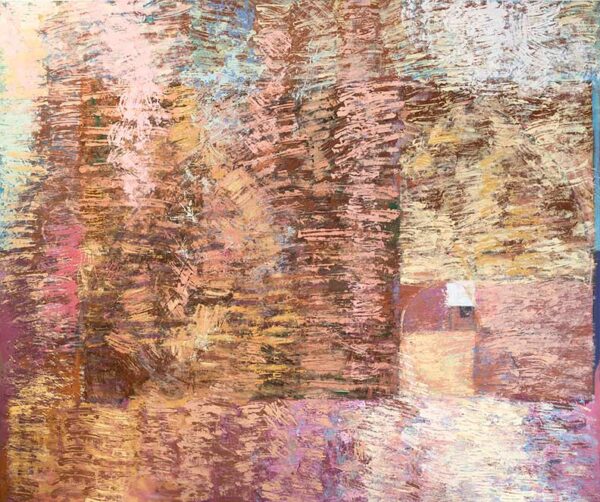

Joe Overstreet, “Kermel,” 1993, oil on canvas, 120 x 144 inches. © Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Photo: Samuel Glass

TH: Yeah, there was no meaning behind it except what I am seeing and feeling, and this one, especially with my color associations, is like a symphony coming out. I started reading about the series; this is the third time we have been in here looking at these. I read that each painting has a specific unfortunate episode it describes, and that he used beeswax to mix with the paint because that gave him the texture he felt when he was in those cells. So every painting is like this deep thing, and I am glad I know each story. It is incredible what he did on that trip and what came from it, but I like to see it without any information first and then…

JBL: See, isn’t that nice? Shouldn’t people do that with music? Don’t be so referential. Just listen to it. Don’t try to guide the listener to what you think they should hear. It is either there or it isn’t. That’s it. I like that.

MB: I love it. He said that he didn’t want to paint sorrow. He wanted to go beyond it. He wanted to face it and acknowledge it, but go beyond it. And these are so life-affirming.

JBL: For sure. The paintings also have these moments, when I think about these two or these two. He has unique moments in each piece that draw the eye. Immediately, I’m thinking about that white box right there. All of that draws us to that one white box that isn’t completely covered. Wadada Leo Smith used to have us listen to music when I was at Cal Arts, and he would ask us to find that unique moment, something in the piece that doesn’t happen anywhere else. I take that to other places in my life, like looking at these paintings.

The Flight Pattern Galleries:

We stop in front of the work Untitled, (1972) in the center of the above image, on a wall of its own.

TH: That’s what I see when I am playing with a rhythm section.

JBL: Yeah, that’s what’s up.

TH: I walked in here and thought, “Ok…there you go!” I am studying this French composer, Olivier Messiaen, and writing music for the Hamburg Radio Jazz Orchestra again. It’s original music, but I am only going to use his concepts to write it. I’m reading books about his bird studies and all this stuff, but when we walked in and I saw that work [referencing Untitled,(1972)], it looks like what I see when I listen to this piece he wrote called the “Turanaglila Symphony.” If you just listen to the first movement, for me, that is this work.

JBL: It is interesting, speaking of the French, one of my favorite philosophers, Henri Bergson, talks about intuition, and I think about this when it comes to melody. A person who is analyzing something, like we are analyzing this piece, knows all the dimensions and everything, but they are outside of the object. He said a person who is using their intuition becomes the object. It is not enough to play the melody and analyze it; you have to become it, which is an entirely different way of thinking.

TH: It’s true, you have to embody it, and that’s what makes it honest.

MB: I really love these because I feel like they are asking for somebody to communicate with them with music or movement. I would love to dance in this gallery, and have music performed.

You know, when you are in a space like a home or a place where you spend time and you really love it, and then you have to leave it or say goodbye to it, and you come to this realization that all the stuff that’s good about that space is really inside you and with you always, and it isn’t really left behind. The idea of the portability of these works really resonates with me. Like he said, you can just roll your artwork up and take it on a plane with you. These works feel like what it means to take the best parts of something with you.

JBL: Overstreet, do you feel he is getting to you? It is this whole idea of feeling something in your body. That is what makes the work powerful. He is communicating an idea, and that is essentially what all art is; all art is about the communication, the quality of communication. Like Don Cherry said, “I want my music to be of mind and of feeling.”

And he succeeded.

Joe Overstreet: Taking Flight is on view at the Menil Collection in Houston through July 13. The show is organized by Natalie Dupêcher, Associate Curator of Modern Art at the Menil Collection.