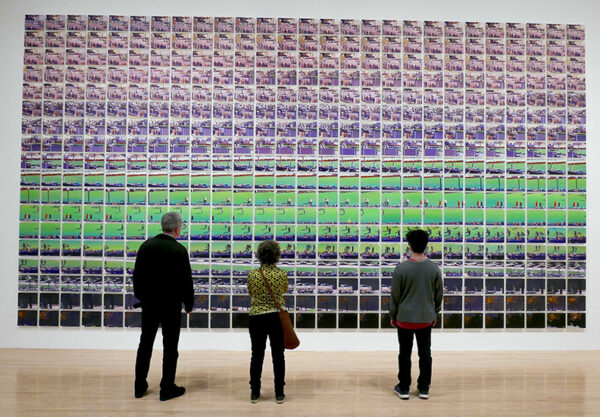

Installation view of “Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968.” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (MOCA) has mounted a momentous exhibition called Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968 that dramatically expands the canon of photorealist art. Too often framed as a short-lived movement of white male artists in New York and the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the conventional canon was established by gallerist Louis K. Meisel in 1980, with 13 White artists, only one of whom was a woman. MOCA director Johanna Burton notes that Ordinary People challenges that view by including “the underrepresented — people of color, queer people, and others belonging to diverse, intersectional communities — in all of their specificity.” As Burton also points out, “many Black, Latinx, and women artists in this exhibition were working at the same time as the canonical photorealists yet have not previously been recognized as part of photorealist art history” (“Director’s Foreword” to the catalog, p. 7). Organized by MOCA Senior Curator Anna Katz with Curatorial Assistant Paula Kroll, the exhibition includes more than ninety paintings, drawings, and sculptures by forty-four artists.

Installation view of “Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968.” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In reconfiguring a span of six decades, Katz views photorealism not as “an end to painting, figuration, representation in the 1960s — but rather as the beginning of a practice that continues to this day” (“Curator’s Acknowledgements,” p. 11). In her essay, Katz notes the low status many accord to the movement, for various reasons. Some see it as “a last-gasp bid for skill, a death rattle for painting;” others see it as “mere copying” (and lacking the creativity and vision inherent in genuine art); yet others see it as “a nostalgic, reactionary attack on the avant-garde project of modernism,” and thus a backward blow against their teleological view of artistic progress. Its very methods are sometimes regarded as a condemnation, “since, in choreographing the shallowest of relays between the surface of the painting and the surface of the photograph, it occupied an infinitesimally slight field of inquiry.” In a further self-limiting move, it takes on the shallowest of subject matter: “the thin veneer of modern life.” Moreover, in the rarified context of the art world, photorealism carries the “fishy” whiff of populism — anything so accessible to the uninitiated masses must be suspect, right? (“What’s so Real About Photorealism?,” p. 15).

Installation view of “Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968.” Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

But in examining the history of repressed or previously unrecognized artists, Katz understood why a photorealist mode of painting was/is so appealing to diverse artists: it is “a rich source of meaning,” both for the artists and their public, who “wish to recognize themselves in art” (p. 15). Ordinary People turns the photorealism canon on its head by prioritizing the marginalized and short-shrifting the canonical.

Three Canonical Photorealist Artists and Paintings

I begin by examining three canonical works before turning to groups of the formerly excluded, particularly Chicano, women, and Black artists in Ordinary People.

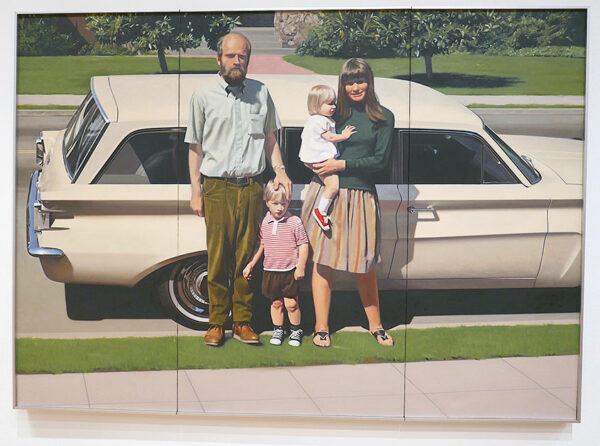

Robert Bechtle “‘61 Pontiac,” 1968-69, oil on canvas. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

When Meisel formulated his concept of photorealism, he meant works that not only utilized photographs as source material but that also imitated the look of photographs to a high degree.

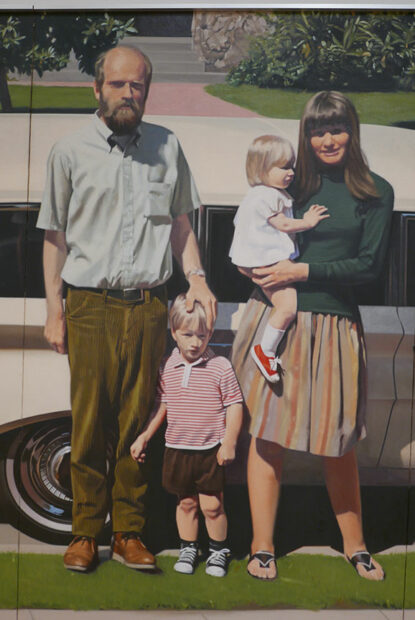

In the above photograph, Robert Bechtle is posed with his family in front of the family car. He replicated a slide by tracing the outlines of the various forms onto his canvas, attempting to create a style-less style. Rather than suppressing or compensating for the distortions and strange effects in his slide, such as the sharp geometrical shapes reflected on the rear window of his car, or the jagged shadow cast by his head, Bechtle imitated them as faithfully as possible.

He stands straight up, while the child by his side turns towards him, and his wife leans in the other direction. The windows on the visible side of the car are largely opaque, though a small slice of transparency cuts across a portion on the left. Rather than making conscious decisions about how to render all the various details, Bechtle simply follows the example of the photograph.

Robert Bechtle “‘61 Pontiac” (detail), 1968-69, oil on canvas. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Bechtle must be placing his weight on his heels, since the front of his feet are rising up, such that he almost seems to be floating off the ground. Moreover, with his hand on his son’s head, he almost seems to be pushing off in order to rise up into the air. Other strange effects include a dark shadow line that runs across his wife’s face, obscuring her eyes. Her striped dress looks bleached-out in places. This is almost certainly not a consequence of faded or bleached material, but rather a quirk of the slide (taken in bright sunlight) that served as the artist’s source. Each and every photographic detail, however strange or unusual, is transferred to the canvas, which is why this is a photorealist work. A non-photorealist painting would not imitate its source so assiduously.

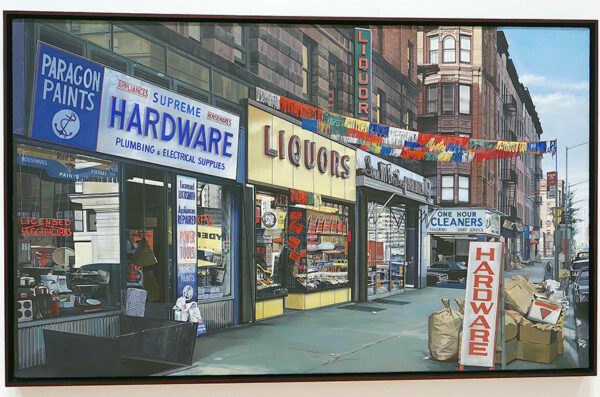

Richard Estes, “Supreme Hardware,” 1974, oil and acrylic on canvas. Collection of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Whereas the Bechtle discussed above was a vision of middle-class White suburbia at high noon in California, Richard Estes renders New York City, not in its towering glory, but at its most humdrum and ordinary. Estes’ painting is dominated by three storefronts (a hardware store, a liquor store, and a pharmacy) with highly reflective glass windows. They are particularly complex elements, owing to the fact that they are partially transparent and opaquely reflective. On the right, a pile of boxed and bagged refuse gives way to crumpled papers in the gutter. The painting makes no attempt to elevate and glamorize, nor to bring down and condemn. It simply reflects an instantaneous slice of time captured by a camera, transposed as methodically and carefully as possible into paint. The important artistic decisions are made in the course of choosing and photographing a particular scene.

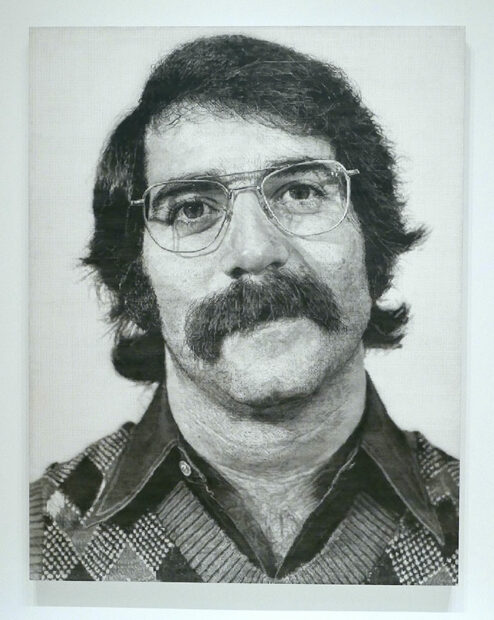

Chuck Close, “Robert/104,072,” 1973-74, synthetic polymer paint and ink with graphite on gessoed canvas. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

As noted above, the art establishment has often taken a dim view of photorealism, to the extent that it has regarded it as art at all. The most notable exception to this attitude is the body of work by Chuck Close that depends upon a rigorous grid system. This group of paintings bears a clear — if somewhat perverse — kinship to minimalism, a contemporary movement based on grids (sometimes actually composed of grids) and other strictly geometric structural units.

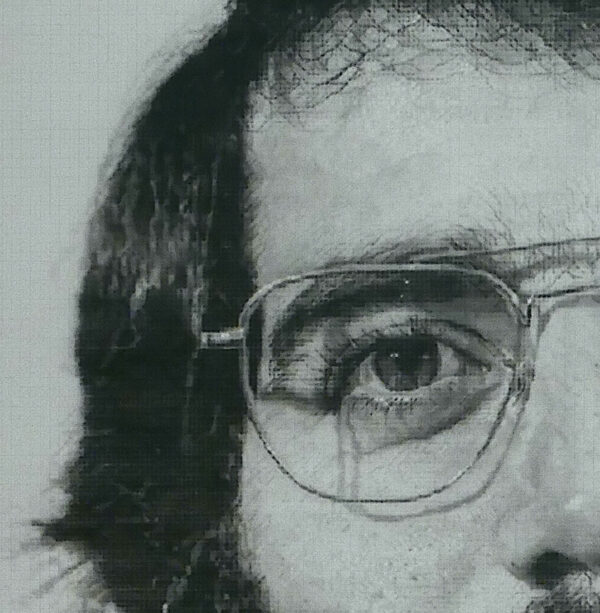

Chuck Close, “Robert/104,072” (detail), 1973-74, synthetic polymer paint and ink with graphite on gessoed canvas. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In this detail of the upper left section of Close’s painting, one can see the grid pattern on the left. As noted in the title, 104,072 tiny squares are utilized to make the painting. Particularly along the hairline on the subject’s forehead, the metal rims of his glasses, and his eyelashes, one can see airbrushed effects that mirror, avant la lettre, pixelation in digital scans.

Chuck Close, “Study for Robert/104,072” (detail of one of four parts), 1973, pressure sensitive tape, airbrush, pen, ink, pencil, and colored ballpoint pen over silver gelatin print mounted on foamcore. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Close’s maquette for his painting comprises four photographs, over which he drew grids, overworked with airbrush, pen, ink, pencil, and colored ballpoint pen. The grid patterns are much more evident in the studies (such as the one above) than in the finished painting.

Over the fourteen months he worked on the painting, Close utilized his airbrush an average of ten times per square, resulting in over a million touches. These repetitive actions caused the artist to develop arthritis. Curator Katz repeatedly emphasizes the manual labor and craft-like processes required by photorealist techniques. But, especially in the case of Close, I would place equal emphasis on the ingenuity and complexity of the systematic method he devised to create this body of paintings.

Latinx Artists

I curated the 2009-10 Jesse Treviño retrospective at the Museo Alameda in San Antonio, at which time scholars lamented the exclusion of Chicano artists from photorealist exhibitions. Consequently, I was very pleased by the significant presence of artists of color in Ordinary People, as well as their high level of visibility.

A banner (reproduced above) with an image by Treviño greeted visitors descending the staircase to the museum entrance (it was also utilized in other locales, as was a banner featuring work by John Valadez).

Photomural with “El Progreso” by Jesse Treviño and a visitor at the entrance to the “Ordinary People” exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

I was startled to see an enormous photomural of the same painting at the entrance to the exhibition. When visitors came to the actual painting (visible in an installation shot above), many were surprised to find that it was not an enormous painting (it is 50 x 60 inches).

Treviño traveled a unique road to Chicano art. He was at the Art Students League in New York, working in a painterly manner, when he was drafted. Suffering grievous injuries in a Vietnamese rice paddy, Treviño resolved to return to San Antonio if he survived (see my 2019 Glasstire article: “A Baptism of Fire: Jesse Treviño Paints ‘Mi Vida’”).

Near death, Treviño realized that he “had just painted whatever my teachers told me to paint… I had never painted my mother or my brothers. I’d never seen museum-quality paintings of the barrio… It made me want to survive to be able to paint the things that mattered most to me” (see my 2016 San Antonio Report article: “Jesse Treviño: ‘Synonymous with San Antonio’”).

This vision of a new artistic path enabled Treviño to cling to life, to persevere during a lengthy rehabilitation, to overcome the amputation of his painting hand, to learn to paint with his left hand, and to deal with lifelong chronic pain. Treviño became a photorealist painter because he wanted his art to be intelligible to the broadest segment of the public, especially to a Chicano public.

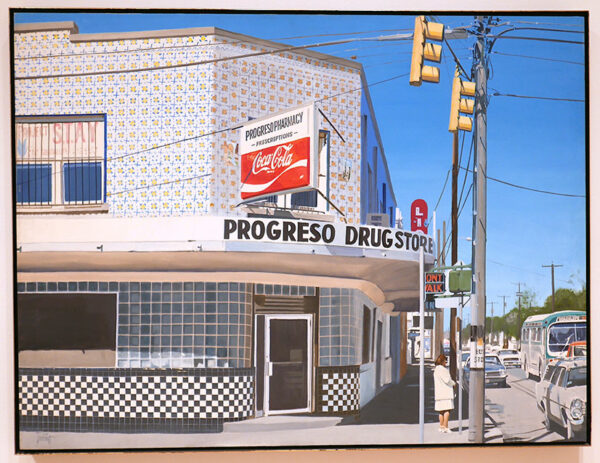

Jesse Treviño, “El Progreso,” 1979, acrylic on canvas. Collection of Kathy Sosa. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The beautifully tiled Progreso building, site of a former pharmacy, is a historic building on the West side of San Antonio, a predominantly Mexican American neighborhood. Treviño regarded the Progreso as one of the most beautiful and important buildings in the neighborhood. As a pharmacy, it had fulfilled an important function in an underserved neighborhood. Treviño also compared his painting of the building to “a portrait of a person.”

Located at the intersection of Guadalupe and Brazos, it is an area with substantial bus, car, and foot traffic. It is directly across the street from the historic Teatro Guadalupe (Treviño also painted a “portrait” of that building). Treviño likened this intersection to Grand Central Station in New York City because it was the transit nerve center of the neighborhood. Treviño placed a single figure on the corner as an emblem of someone who “would ride the bus and not drive.” That person was, in fact, his mother. The bus displays the route sign “Guadalupe.” Behind the bus, one can see a vintage Mustang, similar to the model Treviño bought with his disability pay (see: “Baptism of Fire”). According to Treviño, this intersection “set the stage for the West side.” It also had deep personal significance for the artist, who purchased a home/studio on that street.

When Treviño photographed the building for this painting, he recalls that it was serving as a Goodwill Center, though it still sported an illuminated Progreso Pharmacy sign, and “Progreso Drug Store” was written on the awning. Treviño included these details in El Progreso.

Jesse Treviño, “El Progreso” (detail), 1979, acrylic on canvas. Collection of Kathy Sosa. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In Treviño’s painting, a faded Project S.T.A.Y. (a non-profit that helps individuals to pursue post-secondary education) sign is visible in the second-story window. In the mid-1980s, the Progreso building and the Teatro were incorporated into the campus of the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center (its predecessor group was formed the year this painting was made), thus ensuring that they continued to play a central role in the life of the neighborhood.

The canonical photorealists painted shop windows that held a multitude of goods and featured complex natural lighting effects. But these shops were not chosen because they were unique, nor because they were somehow central to the life of the city in a distinct manner. Treviño, on the other hand, sought out the most culturally significant buildings, many of which he deemed particularly beautiful. These buildings were important to him and to his friends, family, and ethnic group, especially the Spanish language theaters. If anything, Trevino picked his buildings even more carefully than his human subjects. (I have drawn on my exhibition label and conversations with the artist for the above discussion of this painting.)

When Treviño chose to paint a shop window, he selected one whose focus was religious statuettes. Additionally, he simultaneously showcased several of San Antonio’s best-known buildings in the reflecting window. The Mexican-descended San Antonio community is deeply religious. Moreover, there is considerable civic pride in the best-known San Antonio buildings, such as, from left to right in Treviño’s painting, the Tower of the Americas (built for Hemisfair, the World’s Fair held in San Antonio in 1968), the Tower LIfe Building (widely regarded as the city’s most beautiful building), and the Drury Hotel (formerly the Alamo Bank building). True to his title, the painting is rife with santos (saints) and it features the San Antonio skyline. Thus, Treviño selected this particular subject due to its very specific qualities, rather than because of its ordinariness or generic qualities.

Imagine, as a parallel, a New York-centric shop window, one that featured wares associated with the city, as well as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler building in the reflecting glass. Such a display window might contain a row of small Statues of Liberty, a few toy King Kongs thrown in, and some “I-Heart-NY” mugs and memorabilia for good measure. Whereas the canonical photorealist painters chose their subjects because of their generic-ness, Treviño chose his because of their cultural significance.

I have referred to Treviño as “world-famous in San Antonio,” due to his unparalleled celebrity within the city, and his relative lack of visibility outside of it. Ordinary People will help to make Treviño and other under-recognized artists more visible outside of their immediate circles.

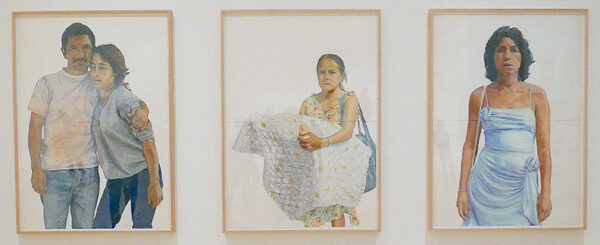

John Valadez, “Robert and Liz,” 1984, pastel on paper, collection of Glenna Avila; “Fatima,” 1984, pastel on paper. Collection of The Bass, Miami Beach; “White Rose,” 1983, pastel on paper. Collection of The Bass, Miami Beach. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

John Valadez, perhaps the quintessential Chicano photorealist artist, is represented in Ordinary People by three pastels. The first depicts his half brother (in a very soiled white t-shirt) and his girlfriend; the second a Latinx woman who manages to hold a partially eaten ice cream cone as well as her baby, which is wrapped in a quilt; the third is an immigrant from Central America, dressed in a tight-fitting blue dress, in preparation for her job as a taxi dancer. All are based on photographs taken by the artist.

As Katz notes in her catalog essay, “Confrontation was seeded in specificity,” which allowed the artist to avoid both media stereotypes (which tended to be negative) and excessive idealization, because of the “detail and individuality that the camera can capture” (p. 22). Robert must have been squinting into the light as he faced Valadez’s camera, while actively pulling Liz to his side. Compositional qualities that stand out include Robert’s gnarled face, the subtle wrinkles and coloristic differentiations on his shirt and faded jeans, and the complex, knotty forms of Liz’s half pulled-up sleeve.

The woman carrying the child, while small in stature, looks very determined. She has a large blue bag, which presumably holds diapers, baby bottles, etc. The baby must be in some kind of crib. Since we cannot see it, we infer its existence by the way she is holding the large blanket that covers it. The taxi dancer seems to look at the spectator very directly, in a manner that she must have utilized to assess her male clients.

The Broadway Mural (1981), Valadez’s magnum opus, was painted at the Victor Clothing Store on Broadway, a part of L.A. that had fascinated the artist since childhood. It is reproduced and discussed in the catalog by Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez (“Chicana/o/x Photorealist Murals in California: Agency, Community, and Photography,” p. 206-7).

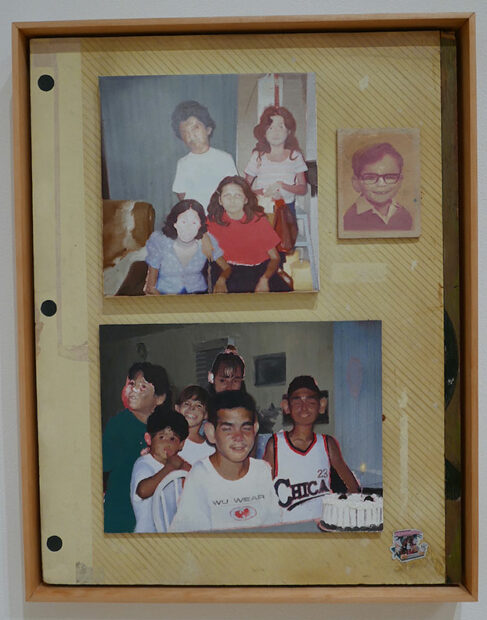

Michael Alvarez, “Look at This Photograph (L-R Primas Locas y El Mike, Flea, Go Shorty It’s Your Birthday),” 2018, acrylic on canvas. Collection of Sylvia Orozco. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Michael Alvarez, who was born in East LA, was inspired by Valadez’s example. Alvarez, however, goes beyond artists who have worked from a single image by painting pages from family photo albums. Look at This Photograph, reproduced above, features three small snapshots mounted on a peel-and-stick album page with diagonal lines. Unlike most photorealist paintings, Alvarez not only works from vintage sources (taken by others), but he also foregrounds the normal wear-and-tear of family photo albums, as well as the casual, amateurish, and low-quality nature of his source material.

In the large photograph in the upper center, the faces of the three girls look like they were blasted out by the flash, while the face of the tallest figure looks deteriorated. This photographic image has suffered damage, whether by accident or by deliberate defacement. The class snapshot of the young man on the right has suffered considerable discoloration. It appears to have been inadequately fixed in its chemical bath. The photo image at the bottom is decidedly humorous. Three of the boys have their eyes closed, their projecting ears seems to be a family trait, and attempts to get the young birthday revelers to smile have not been very successful. Additionally, the cake is cropped at the bottom and on the side. As a conventional document of this event, the snapshot is a failure. As an example of photography’s failure to rise to the ideal, it is a veritable prize. It is not part of Alvarez’s project to replicate his photographic sources with exactitude, so it is highly likely that he exaggerated certain non-ideal qualities for effect. He found the sticker in the lower right on the street, so he may well have taken considerable liberties elsewhere in this image.

Vincent Valdez, “It Was a Very Good Year (Nineteen Eighty-Seven/Eighty-Eight)” (Nineteen Eighty-Seven is pictured), 2024, oil on canvas, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

In this work, which is composed of two large paintings that are installed back-to-back in a small room, the entertainment-industrial complex meets the military-industrial complex.

The painting pictured above depicts Michael Jordan in the act of completing his famous free-throw-line dunk in the NBA’s 1987 Slam Dunk Contest.

Though Dr. J had accomplished a comparable dunk many years prior, Jordan’s flight served as the era’s preeminent symbol of domination and transcendence in the field of athletics. Valdez has selected a viewpoint that makes it seem as though Jordan is not subject to gravity. He looks more like a titan that has snatched a planet from the firmament than a mere hoopster with a ball in his hands.

Jordan’s famous dunk also gave a huge boost to his Air Jordan line of sneakers, which are marketed by Nike. These shoes (worn by an infant in KKK garb) and Jordan’s multi-billion fortune are treated in passing in my review of Valdez’s survey exhibition in Houston, which is traveling to MASS MoCA.

Vincent Valdez, “It Was a Very Good Year (Nineteen Eighty-Seven/Eighty-Eight)” (Nineteen Eighty-Eight is pictured), 2024, oil on canvas, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

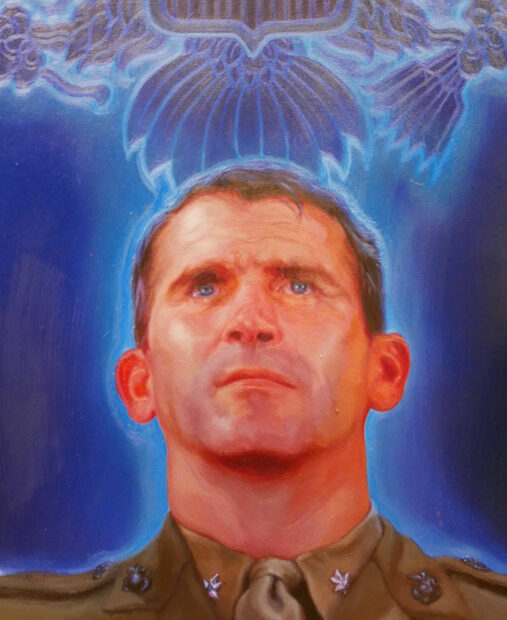

In the above painting, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North takes his oath, just prior to testifying before congress in the Iran-Contra hearings in 1988. During Ronald Reagan’s second term as president, arms were surreptitiously sold to Iran, violating an embargo. Profits were utilized to illegally fund the Contra rebels in Nicaragua, which Reagan called “the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers,” despite prohibitions on such sales imposed by congress in 1982 and 1984.

North took credit for diverting most of the profits to the Contras, while Reagan (combining bad acting with actual dotage), claimed ignorance of such diversions.

Vincent Valdez, “It Was a Very Good Year (Nineteen Eighty-Seven/Eighty-Eight)” (Nineteen Eighty-Eight is pictured, detail of North), 2024, oil on canvas, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

North served as both the loyal instrument and as the sanctimonious face of the Iran-Contra scandal. In Valdez’s painting, he is surrounded by a blue halo, which also engulfs the flags, and which seems to emanate from the Great Seal of the United States of America directly above his head. As in real life, North wore a patch of the Great Seal over his heart. Implicitly, North’s actions stem from the highest authority, and they are garbed in sanctity, or some supernatural force field. Reagan, however, avoided direct implication in aiding the Contras, as did Vice President George H. W. Bush. The latter, when he was president, issued seven pardons in connection with the scandal, enabling the lower-level staff to avoid punishment.

Valdez has collapsed North’s oath-taking (with microphones in the foreground) with his binder, box, and paper-strewn desk. A small picture of Reagan is displayed in the lower right corner. North protected Reagan’s legacy by shielding him from direct culpability. When he left office, Reagan had “the highest approval rating of any president since Franklin Roosevelt” (PBS, “The Iran-Contra Affair,” American Experience).

The television screens that transmitted these salient cultural moments are here aggrandized to the scale of a cinema screen.

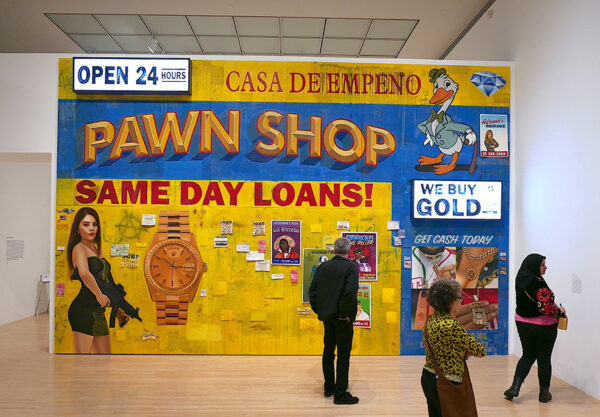

Alfonso Gonzalez, Jr., “American Pawn Shop,” 2024, oil, enamel, latex, dirt, gel medium, and light box on wood panel, courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Gonzalez’s father was a sign painter, and he himself was trained as a billboard painter. Gonzalez Jr. studied at the Los Angeles Trade-Technical College, and he eventually worked as a billboard painter. These skills and experiences were put to good use, as he employs a variety of styles, techniques, and materials to render the facade of a pawn shop, replete with real dirt, aging effects, graffiti, and wheat-pasted posters advertising rap and corrido music.

The fictive facade, inspired by shops in his Boyle Heights neighborhood, suggest pawning a wide variety of objects, including an assault rifle, a gold watch, rings, and jewelry, including a crucifixion pendant. The shop’s emblem is a duck, likely inspired by the Disney character Scrooge McDuck, though, since he sports a bowler hat rather than a top hat (and no spats), he would be a rather poor relation.

Alfonso Gonzalez, Jr., “American Pawn Shop” (bench detail), 2024, courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Gonzalez has even provided a bench, from which to view his storefront.

Sculpture

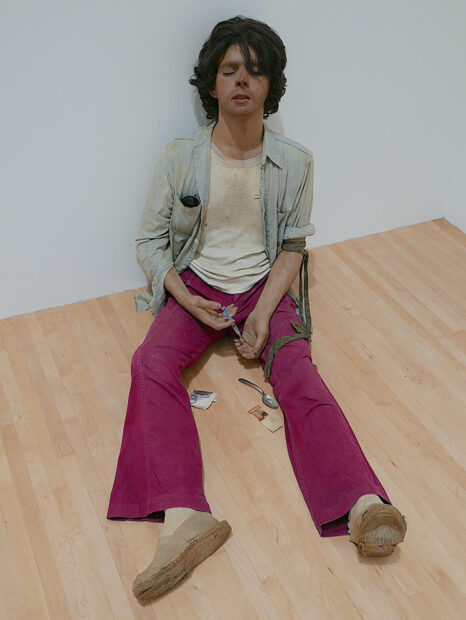

Duane Hanson, “Drug Addict,” 1974, fiberglass and polyester resin, mixed media. Collection of Yale University Art Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Hanson rebelled against the prevailing formal tendencies in art, from Abstract Expressionism to Conceptualism and Minimalism. He pioneered the creation of socially-concerned hyperrealist sculptures that were often included in exhibitions with photorealist paintings. In the above sculpture, a young man holds a hypodermic needle in his hands, while drug paraphernalia is strewn about him. Having tightened a tie around his left arm, his veins bulge out, while bruises or discolorations on his arm suggest that he is the victim of violence or disease. Given his expression, the man has likely shot up heroin. In his early sculptures, Hanson also addressed issues such as homelessness, race riots, death from an illicit abortion, etc.

John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, “Homage to the People of the Bronx: Double Dutch at Kelley Street–La Freeda, Javette, Tavana, Staice,” 1981-82, oil on fiberglass. Collection of The Broad Art Foundation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The team of Ahearn and Torres became community sculptors par excellence in the South Bronx. When John Ahearn moved to the Bronx, he had a background as a filmmaker, working with his brother Charlie, which led him to life-casting. He came in contact with Rigoberto Torres, who was making religious figurines in a shop as a high school student apprentice. They joined forces and created numerous sculptures honoring South Bronx residents, of which Double Dutch is the most famous. In a conversation with Katz, Ahearn referred to these works as “three-dimensional polaroids” (p. 24).

Black Painters

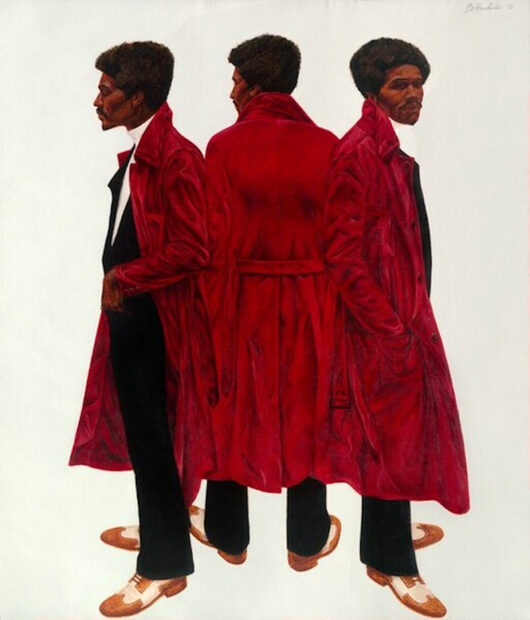

Barkley L. Hendricks, “Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris,” 1972, oil and acrylic on canvas. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Photo: MoCA

When he was a student, Hendricks visited museums in Europe. He was particularly impressed by Baroque paintings, but he also noted the lack of Black subjects as protagonists of painted portraits. Hendricks wanted to capture the swagger of formal European portraits in his depictions of contemporary Blacks. In 1972, he utilized Anthony Van Dyck’s triple portrait of King Charles I (which was created as an aid for the Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bernini) for his portrait of Willie Harris.

Hendricks’ triple portrait is suave and sophisticated. We can compare it to Kehinde Wiley’s Louis Philippe Joseph, Duke of Orleans, painted a generation later.

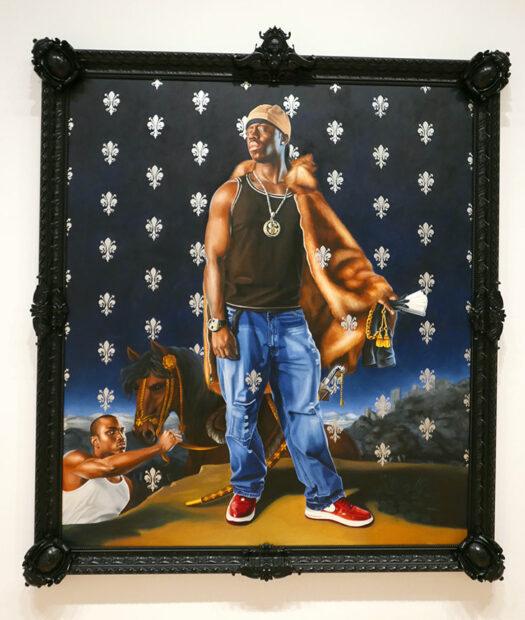

Kehinde Wiley, “Louis Philippe Joseph, Duke of Orleans,” 2006, oil on canvas. Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Wiley has made a career of rendering portraits (mostly of Black men) in poses taken from Old Masters. The quality of his paintings vary a great deal, as do the degree of their connection to Old Master sources. For my taste, this painting too closely resembles an ad for designer jeans or some other commercial product. The anatomy of the man who is restraining the horse also leaves much to be desired.

Women Painters

Audrey Flack, “Leonardo’s Lady,” 1974, oil and synthetic polymer on canvas. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Audrey Flack was the only female artist included in Meisel’s gallery. Cynthia Diagnault, an artist in the exhibition (her work is discussed below), excoriates the gallerist’s formation of the term photorealism in her essay “The Theory of Everything or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Photorealism,” which is included in the exhibition catalog. She notes: “His photorealists didn’t know each other; they didn’t share ideas or values; and many of them actively rejected the label” (p. 221). Diagnault adds: “many notable artists of the time meet Meisel’s criteria for photorealism, but are still left out of his version of the history,” which is all-White, and overwhelmingly male and American, with one British artist then living in the U.S. (p. 221-222). Given Meisel’s financial connection to the artists he placed in the photorealist category, Diagnault questions whether photorealism constitutes “a real and compelling cultural idea, or just a convenient marketing term?” (p. 222).

For good measure, she points out that artists have utilized photographs “since the invention of photography in 1839” (p. 222). A valid counter-argument to Diagnault’s point would consider the degree to which more recent artists utilized photographs as a model for absolute emulation rather than simply as one of several tools. Rather than address this question, Diagnault tumbles down the David Hockney / Charles Falco rabbit hole. She even expands Hockney’s thesis, which she restates as “there would be no realism without the invention of the camera obscura” (a method of projecting images through a pinhole into a dark chamber), by declaring that the claim “can be applied globally” (p. 223).

One of the highlights of the Ordinary People exhibition was a gallery of women artists titled “Bad Girls.” I start with Audrey Flack, one of Meisel’s canonical photorealists. From the perspective of photographic sources, the most striking aspects of Leonardo’s Lady are the multiple points of focus and the reflections in metal, glass, and ceramic. Leonardo’s Lady is virtually a commentary on photography, without which it could not exist. Only a camera can fix the fleeting reflections, such as those on the gold and silver containers near the top of the painting. Strikingly, the cupid’s elbow is in sharper focus than his feet. We possess a profound grasp of the concept of focus through photography and film, which can reproduce areas that lack focus in a permanent manner. If one tried to capture the effect of something that is out of focus by painting it directly, the very act of concentrating our gaze on that area would serve to bring it into focus. An artist cannot paint something that is blurry out of the corner of one’s eye.

One of the cleverest conceits of Leonardo’s Lady is the reflection of the cupid in the make-up compact, including the cupid’s right hand, which we cannot see on the statuette itself. The reflected cupid is blurrier than the “real” one, precisely because it is a reflection. There are numerous bright points of distorted light, which we also see in works by Vermeer and some Dutch still life paintings from the seventeenth century, which, along with a limited use of out-of-focus areas, constitutes proof that these artists used lenses (and we know at least some of them used the camera obscura). But Flack’s work is a tour-de-force of photographic effects, one that is quite different from the Dutch examples mentioned above. It was enabled by a fixed photograph. Lenses, cameras obscura, and mirrors were tools utilized by some Old Master painters, along with many others, including linear perspective, atmospheric perspective, systems of geometrical proportion for human figures, and many years practicing drawing and learning to paint in layers (rather than directly), with the use of drawings and sketches. They couldn’t have done a painting like Leonardo’s Lady if they had wanted to — and, since this concentration of photographic effects was not part of their cultural milieu, there was no reason to wish to make such a painting. Moreover, our own knowledge and familiarity with photography and film makes us more appreciative of the limited photographic effects we find in the work of artists such as Vermeer and Velázquez. One might even argue that some aspects of their work speak more directly to our age than it did to their own, which is why some artists were dramatically “rediscovered” after the discovery of photography.

Finally, I’d like to point out the humorously “old fashioned,” primitive photograph of the Leonardo painting reproduced in the book near the center of Flack’s painting. Nineteenth-century artists could have rendered such photographs as accurately as possible, but no such movement or photorealist style emerged at that time. Flack frames the Leonardo illustration with audaciously painted elements, such as roses, the cupid statuette, and refractive vessels, foregrounding them as the fruits of modern photography.

Nur Koçak, “Natural Wonders,” 1979; “Chanel Lipsticks,” 1988; “Fruitables,” 1979; acrylic on canvas. Nesrin Esirtgen Collection. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Nur Koçak, who was born in Turkey, partially raised in the U.S., and trained largely in Paris, is represented in Ordinary People by a huge triptych of lipsticks. Koçak recalls that the Paris Youth Biennale in 1971, with a large section devoted to conceptual art and photorealism, “set my path as an artist.” It provided an alternative to the “Late-Cubist” style of her teachers at the academy, who professed: “The artist is not an eye that copies what he/she sees, but the eye that interprets!” (“Narratives Interview Series: Nur Koçak,” July 2021).

Koçak’s critique of feminine imagery, also undertaken in Paris on the basis of magazines and shop windows, led to her Fetish Objects series (1974-88), which included other consumer objects such as clothing, perfume, and nail polish, as well as lipstick. The tallest panel in the exhibition is 76 ¾ inches high, resulting in phallic towers of lipstick nearly six feet high.

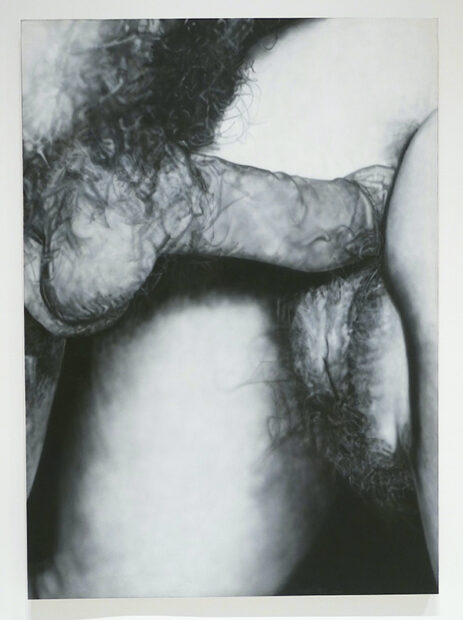

Betty Tompkins, “Fuck Painting #6,” 1963, acrylic on canvas. Collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

With Tompkins, we move from the symbolic to the “real” with one of the artist’s monumental works from her much-censored Fuck Paintings series (1969-74). At 83 ¼ inches high, it is considerably bigger than one of Koçak’s lipsticks, and it has not lost its ability to shock.

Tompkins’ series was sourced from the porn collection of her then-husband, and she utilized a grid system essentially identical to that of Chuck Close (though with larger squares). As the exhibition label notes, “the smooth, cool finish of the airbrushed surface divorces the pornographic image from its erotic function.” The label text also acknowledges that Tomkins’ series is “now considered a significant chapter in the ongoing project of women reclaiming their bodies in the face of sexual objectification.”

The Flack, the Koçak, and the Tompkins are arguably the three most imposing paintings in the entire exhibition.

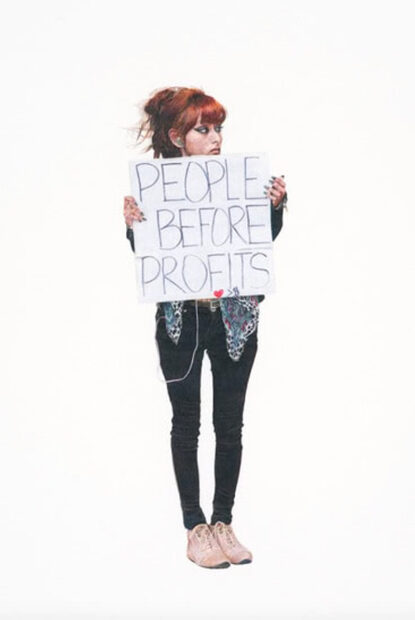

Andrea Bowers, “People Before Profits” (May Day March, Los Angeles, 2012), 2012 colored pencil on paper. Collection of Margaret Morgan and Wesley Phoa. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

On a more modest scale, Ordinary People features two works by Andrea Bowers. A press release for a recent exhibition describes her work as “a Feminist-centric celebration of workers’ rights movements, highlighting nonhierarchical labor organizing strategies and the use of craft, artistry, and pageantry as valuable political tools.” Her work amplifies the messages found in placards carried by demonstrators, always with well-crafted graphics.

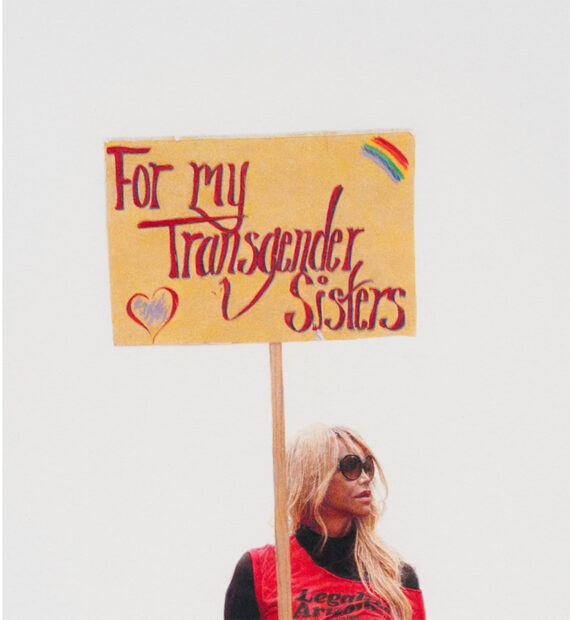

Andrea Bowers, “For My Transgender Sisters” (May Day March, Los Angeles, 2012), 2012, colored pencil on paper. Collection of Phil Mercado and Todd Quinn. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Bowers’ work addresses the intertwined connections between feminism, workers’ rights, immigration, and migrant’s rights.

Three Serial Innovators

Judie Bamber, “Are You My Mom?” series (suite of six works), 2006-2013, graphite and watercolor on paper, various collections. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

I conclude this review with the work of three serial photorealist painters that dramatically expand the boundaries of the photorealist genre.

Judie Bamber’s six works feature a woman in cheese-cakish poses. That woman is her mother, who wanted to be a model. And the images she recreates were made by her father, who was an aspiring artist. As the exhibition label notes, we see that “the intimacy between a man and a woman is being transposed onto a mother and daughter… sexual energy being recharged… onto the loaded territory of looking and being looked at.” These works are particularly complicated reinterpretations.

Cynthia Daignault, “Twenty-Six Seconds” (viewed by three visitors to the museum), 2024, oil on linen, courtesy of the artist, Kasmin Gallery, Night Gallery, and The Sunday Painter. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Abraham Zapruder captured the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963, in an 8mm home movie made up of 486 frames that lasted 26 seconds. Daignault’s brilliant conceit was to transform each frame of this obsessively studied film into an individual painting. As the artist noted on Instagram at the time of the opening of “Ordinary People”: “It took an entire year of my life. (While I had two kids under 4 and was breastfeeding every 3 hours for the duration.) This almost killed me, and there were many days along the way that I thought I would not finish.”

It’s somewhat ironic that the only really good evidence of the assassination was captured by an amateur rather than a professional. The museum label holds that Daignault pried “apart the ways in which photographic images shape the collective memory and understanding of this national trauma.” The label insightfully notes “the continued role of citizen-journalists recording police brutality, mass shootings, and military conflict on smartphones.” Moreover, “by abstracting the film into a series of almost unreadable, loosely painted canvases, Daignault renders an exceedingly well-known piece of history strange and therefore viewable anew in our era of permacrisis.”

Ben Sakoguchi, “Bombs” (suite of 24 works), 1983, acrylic on canvas with wooden frames. Collection of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: MOCA

Sakoguchi’s deeply subversive Bombs utilizes the high-keyed colors of advertising and tourist postcards to treat the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which killed as many as 226,000 people, the overwhelming majority of which were civilians. Sakoguchi was a toddler when, after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, his family was forcibly detained by the U.S. government. They, along with 17,000 other people of Japanese ancestry, were shipped to Poston, Arizona, where they were imprisoned as “enemy aliens.” Nearly all of the Japanese American detainees were incarcerated until the nuclear bombing of the two Japanese cities, for it was these war crimes that terminated the conflict.

With picture-postcard brightness, Sakoguchi documents atomic blasts, as well as nuclear missiles, warheads, and bombs, as well as the planes that delivered them. He also includes the burnt bodies of two survivors of the nuclear attacks on Japan. It is a searing pictorial statement that Katz describes as “a kind of medieval altarpiece made during the height of the people’s movements for disarmament” (p. 28). Now that racial intolerance has reached a feverish pitch in the highest echelons of the federal government, we would do well to remember the injustices and the horrors such attitudes produce.

Ordinary People is a badly needed, wide-ranging reexamination of art (paintings in particular) that could potentially fit into the category of photorealism. It even has a couple of cowboy-themed paintings – and they are rather good! The exhibition and the catalog have provided me with a great deal to think about on this subject.

***

Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968 is on view through May 4, 2025, at the museum’s Grand Avenue location. A beautifully illustrated 256-page catalog titled Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968 accompanies the exhibition. It is co-published by MOCA and DelMonico Books and edited, with lead essay, by Anna Katz. The catalog includes an introduction by MOCA director Johanna Burton, as well as contributions from Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez, Karin G. Oen, Dhyandra Lawson, and Cynthia Daignault. The catalog also has a particularly useful artist biography section.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.