This year the Creative Research Laboratory (CRL) mounted the

traditional summer grad show, except it shifted the structure around:

Where typically a two-part exhibition splits the students into two

groups, each with a theme and a separate catalogue, this year saw a

three-part exhibition swap-out.

Peter Johansen...The Enola Gay Caught in the Sails of the Mayflower...2007...Enola Gay Model, Mayflower Model and Card Table

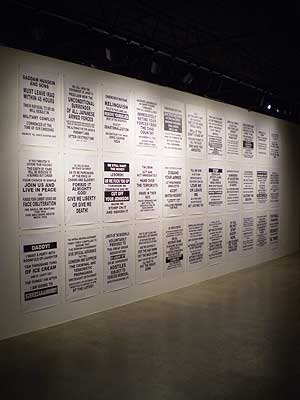

Each show had two themes (and titles), with a catalogue essay written about each theme, and a selection of grad student work, some of which fell into more than one of the stipulated categories. In a sense the CRL was finally being used as perhaps it was originally intended — as a laboratory to experiment with the trading in and out of work and of the various lenses through which each exhibition presents it. After seeing all three exhibitions, I was curious to speak with the curators or art historians about the behind-the-scenes process of creating this year’s shows: How the idea came about, how the themes were decided on, how this potentially related to their “studio practice” as curators, and in the end how each of them felt about the work itself and the exhibitions as a whole. Below is a dialogue that was conducted through an online interchange where each of the curators was asked to contribute to a shared document.

Rachel Cook: After reading an essay introducing the idea of “interchange,” I was particularly interested in the idea of creating a model that differs from the previous summer graduate exhibitions. Can you talk about how the idea came about exactly, and what made each of you decide on this format of a series of exhibitions?

Amanda Douberley: The CRL summer schedule allows for two three-week exhibitions, so the most logical option is to do studio visits, and then divide interested MFA students into two groups. The spirit of the shows has been to include any grad student who wants to participate, so the curatorial process can feel a bit like connect-the-dots. You have to make everyone fit, which can lead to pretty broad themes; these broad themes, in turn, inevitably leave you with artists who could have gone either way. For me, this was the most frustrating part of dividing by two when organizing the other grad summer shows I have worked on: Murmur and Superstring in 2003, and threads and in::formation in 2004. The decisions we had to make on where some artists would go seemed fairly arbitrary — really just based on numbers and on creating a balance in terms of the space within the gallery. There was no way to talk about how some artists could have straddled both exhibitions, or how two very different themes/curatorial arguments could address a single artwork. Creating two shows also can lead to a focus on polar opposites, which we saw last year with Making It Alone and Making It Together, and the year before that with Fever and Shade. From the start, we definitely leaned toward finding an alternative to the binary model this year.

Lynn Boland: I had volunteered to work on the exhibitions this year with a binary division already in mind. It was an interesting idea that I’d like to pursue at some point, but once Amanda articulated the problems with year after year of binary divisions, I think we were all in agreement and ready to find a new way to organize things. We were discussing this issue having just visited Karri Paul’s studio, and her technique of creating an image, then rearranging it — adding and subtracting pieces — to form a new image, seemed to me a perfect model for what we wanted to do, at least as a conceptual starting point.

Edwin Stirman: When we sat down to articulate and reminisce about our various experiences from past exhibitions, and we started thinking about the overall dissatisfaction with binary representation, I remembered a lengthy discussion in a class with Richard Shiff about binaries. It seemed that a good way of removing the tension between two poles was to complicate it by adding a third element to form a triad of associations. With six curators, the math worked out that we could each step off into further complicating the exhibition by taking charge of one of six themes.

AD: Yes, the math: one exhibition divided into three parts made up of two themes each. Having six curators is a tough balancing act — at times I didn’t think we would get past figuring out what to call the whole thing, let alone selecting artists and then working out the installation — so giving each person his or her own piece of the show to work on was a good solution.

RC: The themes of the exhibition discussed in each essay vary tremendously — from adding-and-subtracting, history, eternal moments, fantastical worlds and the problems with representation to discordance. Did each of you pick the work first or the themes? Or rather how did each of you come to the themes discussed in each of your essays?

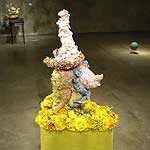

Kathryn Hixson: Themes presented themselves as we did studio visits, coming from the work itself. I noticed several artists grappling with a desire to make representational painting and sculpture, but coming from a variety of directions, experimenting with the painted surface, sculptural materials like ceramics, or found imagery from literature or mass media. As themes begin to emerge, they didn’t become mutually exclusive. We realized that any one body of work could easily accommodate itself to at least two themes, even as disparate as those ended up being.

LB: We had all been taking notes on different themes we saw running through various artists’ works. Initially, I think this was with the idea of narrowing down the number of artists included and putting together two discrete exhibitions. However, once we decided to try an “add and subtract” approach, as Kathryn notes, we realized that there was plenty of overlapping in different themes, both between artists and within individual bodies of work, to allow for what we finally put together. The whole process was fairly organic. We arrived at the themes during studio visits, and then found a way to include as many of the themes as possible. We wanted at least one “bridge” figure in each of the three shows, so that was really the determining factor in pairing the themes. Although a somewhat arbitrary arrangement in one sense, it seemed to work well for the issues we were interested in exploring.

RC: As an artist who is interested in curating, I find organizing exhibitions a little like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. It is interesting to think of this three-part series as part of your “studio practice” for curating. How did each of you think about the layout and the evolution of the exhibition over the course of the summer?

LB: I think that’s a great analogy. We had an idea, but we also had logistical and material restraints, so the process of putting the themes together, as well as the actual arrangement of work in the gallery, is really something of a negotiation between a priori and posteriori reasoning. We started with the broad idea of wanting to disrupt and complicate the typical binary model. Then we refined our ideas while talking with the artists and spending time with the work. Edwin and I had a basic idea of how we wanted to arrange things as we started installing the third segment of the show this week; however, we’ve certainly adjusted our ideas along the way.

KH: I came up with cutting the gallery space along a diagonal, with one curatorial project on either side. I hoped relationships between pieces would ricochet across the room to form ever-changing contexts, invoking shifting, evolving interpretations as viewers moved through the gallery. The memory of the last set of groupings would reverberate against the second and third, thrusting work into new relationships.

AD: A lot of what comes together with a show inside the gallery can be pure dumb luck. As Edwin told me this week, that’s why installation is the best part. For Part I, for example, we had sculptures by Alec Appl in “The Eternal Moment” and paintings by Virginia Yount in “The Burden of History.” They ended up next to each other along this diagonal line we were using — following Kathryn’s lead — to split up the gallery, and they rhymed really well. It was totally unexpected.

LB: That was really the main idea behind my conception of the general organization, and even the title Interchange, although I don’t know that I could have articulated it in those terms until now, having seen it all happen and having had the chance to take part in this discussion. It’s also an underlying part of the idea behind my theme for the show, “Add and Subtract,” I suppose. Here, specifically, I focused on subtractive techniques used to add formal elements, but in a broader sense, I wanted to help elucidate the role studio practice can play in developing ideas. I think that’s something that can easily be overlooked by art historians who don’t occasionally — or at least at some point — get their hands dirty and make things. Sometimes we imagine a grand plan, fully worked out from the start, when often conceptual innovation can come from technical adaptation. The CRL really helps make this sort of thing happen at every stage. It’s not at all unusual for some of the pieces in the shows to still be “wet” when they go on the walls, and the CRL staff is amazingly accommodating to artists and curators, from planning to installation.

RC: After reading some of your bios, I was curious about how each of you viewed work being made at the University of Texas, in comparison to your travels or to your own research for your dissertations.

KH: The MFA students at UT are clearly part of the national and international discourse about current art making. The three-year MFA program allows for a great deal of refinement within their projects, more than I’ve seen in shorter programs, though there is also the same troubling amount of careerism here as in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. I think that UT students are exemplary of today’s mood, which I have identified everywhere I’ve been this summer: A healthy embrace of art historical tradition — be it figurative painting, ceramics, film or straight photography — that is energized with an almost giddy sense of the present, and a wary but hopeful venture into the future.

RC: In addition, one of you (Deborah Spivak) said she was a little afraid of writing about living artists. How does this really differ from writing about dead artists?

Deborah Spivak: I try to be funny, but sometimes my jokes don’t transfer to paper. When I discuss my thesis topic with art historians who study art from the Western tradition, they get disgusted by the gore of severed human heads. I was trying to imply that when writing about dead artists (or, in my case, art made by nameless artists), the art historian does not have to worry about being corrected by the artist. For me, the study of art is a search for the truth behind the work. I had never written about contemporary artists before, and I found myself getting quite nervous about misrepresenting the art or the artist. It is a new experience for me to be able to ask someone why he or she made something a certain way. In my discussions with the artists, I found that some of my interpretations were wrong, and there were some important concepts I hadn’t even considered. In my current research, I am trying to break down the symbolic system of a culture that had no writing. So in my work art represents culture, but in this case art represents whatever the artist wants. It’s a very different way of looking at the aesthetic. Also, contemporary art doesn’t usually involve the manipulation of the remains of a sacrificed individual. If it did, I would be even more afraid of writing something the artist didn’t like.

AD: There are a ton of things to think about when you’re working with an artist on an essay. Sometimes you can end up with more or less a transcript of the studio visit. But I hit a moment that felt really right with Laura Turner. Great essay material came out of our discussion in her studio, and I used some of it, particularly in terms of the size of her photographs, but I also had this idea about her photos and Dutch still life that I ended up pursuing as well in my essay. I sent her a draft, knowing that it had a bunch of technical errors, and in her response with details about the right kind of camera, film, etc., she said the new information wouldn’t affect my essay. That fine line between my argument and her work pretty much sums it up right there. Maybe the best I can hope for with an essay coming out of the studio is that I can say something different or new or whatever in a way that resonates with the artist. If I were going to parrot someone, I probably wouldn’t want to write about her.

KH: I view an artist’s intentions, whether the artist is alive or passed on, as an important aspect of the work. Like process, materials, style, scale.… Still, intention may or may not affect how I understand and judge a work of art.

RC: The work that most excited me in the exhibition was that of Kurt Mueller, Jill Pangallo, Anna Krachey, Peter Johansen, Alec Appl, Amelia Winger-Bearskin and Virginia Yount. Can each of you weigh in on your various perspectives on these artists, and on whichever one (or more than one) each of you is most interested in?

DS: I don’t want to play favorites here, but I was very drawn to Peter Johansen’s work. He is asking the same questions about history, culture and the institution’s role in their dissemination that I am. The beauty of his work is that the viewer has to put in the effort to think a little in order to get something out of it. His works aren’t really aesthetically pleasing. And while they allude to literary culture or written history, they are not so cerebral that they are out of reach. His works challenge academia in a healthy, devil’s advocate kind of way. He forces the viewer to question the type of knowledge that comes from books rather than experience. He makes these questions tangible so that the viewer walks away with a visual memory of an impossible hypothetical. What would happen if the Mayflower and the Enola Gay got in a fight? No. Really. What would happen?

KH: We curators agreed to group these artists’ work into these shows. Enough said!!

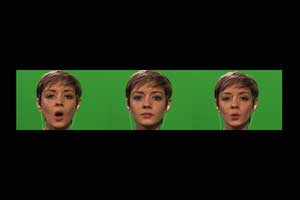

LB: Well, not wanting to play favorites either, I do think it’s useful to discuss what it is about the artists we personally chose to work with that made us want to work with them, so I will say more. I found myself responding particularly strongly to Amelia Winger-Bearskin’s work, especially Backup (2007), which is in this show. The audio component of the video is right up my alley, since my dissertation concerns early 20th-century notions of the “emancipation of the dissonance,” and Winger-Bearskin has created atonal music from tonal components (really like many of Bartok’s compositions). However, there is so much going on in the work, I didn’t focus much on that issue in my essay. As I mention in a footnote, I also connected personally with the idea of highlighting the support structures of popular culture, which is really the crux of the piece, so I focused more on that aspect. This speaks to some of the questions above, too. Although my own research involves issues that overlap with elements in the work, I wanted to approach the video, at least at first, from the artist’s point of view rather than my own. This is, I think, possible with artists who are living or dead, but it’s particularly convenient to get a sense of the artist’s intention if you both spend most of the day in the same building and if you can talk about the work off and on over the course of a few weeks. I was also able to introduce some ideas that weren’t present in Winger-Bearskin’s creation of the video but that added something to the discussion nonetheless. One thing that really fascinated me as I was writing my essay was that with only a small shift in perspective from the artist’s studio practice to my reception, the audio could go from polymodal and polymetric (three different key and time signatures operating at the same time) to their apparent opposite: atonal and ametric. One of the things I love about Winger-Bearskin’s piece is that although there is a clear idea at play — cleverly and engagingly presented — it doesn’t close off interpretation, but rather frames other related ideas I have floating around in my head in a new way. So, to give another example, although the artist wasn’t intending to comment on the history of rock ’n’ roll itself, or underappreciated contributions on that level, it was still valid and useful for me to address that issue in my catalogue essay.

RC: After observing three years of summer shows at the CRL, I think Interchange is the first exhibit where I felt the art historians were pushing themselves creatively as much as the artists were. How did each of you feel about this year’s exhibitions in comparison to the past, and do you have a sense of how the artists who participated felt about it as well?

AD: The CRL grad summer shows have been primarily an educational experience for most of those involved. Speaking for myself, I had never done a studio visit or curated an exhibition prior to the first shows I worked on here. I really feel as if I apprenticed under Charlotte Cousins, who initiated the exhibitions with Atteqa Ali in 2002. When Charlotte sent out an email during the spring semester of 2003 inviting art history grad students to get involved, I ended up being the only one to respond, so we did everything for Murmur and Superstring together, right down to co-authoring the curatorial essays. And I have to say, lucky me! I remember being pretty quiet during studio visits and totally blown away by the questions Charlotte came up with, on the spot, to ask artists. She drew up the schedules and spearheaded everything from PR to installation. It was a fantastic experience for me and most likely a ton of work for her, but I feel I’ve benefited immensely, and can only hope others have had a similarly transformative summer at CRL.

The following year I took up the reins with Eric Zimmerman, an MFA student who had showed in Murmur and who was interested in curating. We had eight curators in 2004, and in 2005 we handed over the shows to two of Eric’s threads co-curators, Laura Lindenberger and Alex Codlin. This pattern of two-year tenures working on the summer shows — with an “apprenticeship” year as either a curator or a catalogue essayist, followed by a year leading the curatorial team (and a third year, I guess, as a grandparent to the shows) — continued up until this year, when the torch didn’t get passed directly. Instead we ended up with two-thirds of the team’s having participated in past exhibitions (Lynn as a curator in 2002; Edwin as a curator in 2005 and an essayist in 2006; Katja as an essayist in 2006; plus me), and two curators — Deb and Kathryn — who had not, although Kathryn has us all beat in terms of curatorial know-how. So rather than one or two leaders, we had a good amount of collective experience to inform our decisions.

With the artists, it seems there are more opportunities to show in Austin since these exhibitions started, so I felt confident our somewhat kooky curatorial premise would read a little bit better for them now than it would have in 2002 or 2003. In the interim, MASS (a gallery space run primarily by UT-Austin grad students) has started up, along with Fluent Collaborative, Art Palace and Okay Mountain, and the now-defunct Donkey Show and UT’s Gallery 3 at the Co-op. All of these spaces have shown the work of current grad students, offering exhibitions and experiences that didn’t exist three or four years ago. Perhaps, as Kathryn said, this is a manifestation of larger trends in careerism for artists. Regardless, it signals a change for the CRL grad summer shows. I have no idea what that will mean for the shows materially, but I’d like to think there will always be another year to figure it out.

LB: Like Amanda, I too feel as if I “apprenticed” under Charlotte Cousins and Atteqa Ali. I had some previous experience working in galleries and museums, but before the Process and Jacket shows in 2002, I had never done a studio visit. I can really relate to what Amanda said, having had a similarly transformative experience. As for the creativity involved in this year’s show, I will say that although I’ve always thought of myself as a fairly creative person, and have always had musical and visual projects going, until this year my academic pursuits and my creative pursuits were fairly separate. Our department encourages a creative approach to scholarship, but for me they’d always been pretty divided until I read Lucy Lippard’s Six Years (1973) while working with John Clarke this year. That really made me make a concerted effort to integrate my pursuits more. It has, I think, been to the benefit of everything that I do. So, that’s an important source for the upsurge in creativity in my contributions to the show. Interchange was a great opportunity for experimentation for us all, since everyone involved was thoroughly receptive to trying new approaches. It really was an ongoing dialogue from start to finish. I think the artists involved in this year’s show — at least those that I’ve spoken to about it — have been pleased with the way we’ve organized things. It was a little confusing for us all at first, but as we got it worked out, it seemed our initial premise of highlighting the plurality of meanings in any given work of art really worked, so I think we’ve all been happy about that.

Images courtesy CRL and the artists

This dialogue took place over the Internet during the month of August. Glasstire would like to thank all the participants for trying this type of interview, particularly one of our contributors, Amanda Douberley who assisting getting this discussion off the ground and organizing the format.

Rachel Cook is the Editor of Glasstire.

1 comment

Thanks for this interview, Rachel! It really reminds us how much forethought and research goes into these shows. I like the email format…