To call upon “animal spirits” is to invoke the irrational and uncontained. John Maynard Keynes, economist and philosophical forebear of the welfare state, renewed the term in the 20th century in order to explain investment decisions based not on logical outcome but on sheer risk. To boil this idea down to fewer words, it is the spirit of the gambler. From those who have found upward mobility in rising interest rates, to those with credit card debt, student loans and mortgage payments that are almost too much to pony up for — you, my friends, are living by animal spirits.

Feral Nature is a tight multimedia show in the Main Gallery at the UT Dallas Visual Arts Building in Richardson, on the un-feral edge of Dallas. Focused and cohesive, this exhibition is all about animal spirits. Curated by Margaret Meehan, the show riffs on the old postmodern idea that the emotional subtext is not separate from rational decision-making. The soupy morass of subjectivity, in fact, contains the seeds of action. Feral Nature thus rips away the proper clothing of Enlightenment thinking to show the curly tail of beastly subjectivity.

After some 25 to 30 years, the critique of rationality may seem a well-worn idea. Nevertheless, to reinstate the wild unknowingness of the human beast, to admit the fundamental errors of reason, is timely. We can relish, if only for its four-week run, the flashy, scruffy, irony-clad reprisal of a presidency claiming rational control while the world is running amok.

Yet we can find political solace in the “animetaphor” of Feral Nature without being hit over the head with reductive or literal references. This is not an overtly political show. It only becomes political when we take time to think about the repercussions of what Gilles Deleuze once called our “becoming-animal” nature. To admit that we are all ass-sniffing, knowledge-wielding accidents of nature is not so much to celebrate ignorance as to recognize the folly of sure-footed thinking. It is to own up to the fact that knowledge begins with doubt. Let us not forget that René Descartes prefaced his cogito ergo sum , “I think, therefore I am,” with dubito ergo cogito , “I doubt, therefore I think.”

The young artist Clayton Hurt makes animal mayhem out of steel, burlap, wax, wood and tar. Hurt’s three dog sculptures are cheeky in the way of the dog philosopher Diogenes, who “lets a fart fly against the Platonic theory of ideas.” In Rock n Roll , Hurt has given us Toto with a penchant for fast food. A small black terrier made from burlap and wax on a steel armature stands on a square podium with one paw in an empty Styrofoam hamburger container and another holding a small sign reading “Rock n Roll McDonalds.” Hanging in the corner is Hurt’s rather gothic Light Dog, an eviscerated Santa’s little helper in red and black. Finally, his Catch 22 looms over the whole exhibition. Mounted on the large central wall in front of a broad sky-blue swoosh of paint, a tan shepherd mix holds a Frisbee in his mouth in mid-catch. The striped sweatbands on the dog’s wrists and ankles bring to mind the heroics of past eras in an Olivia-Newton-John-meets-the-Greatest-American-Hero kind of way. These works show not only the incredible talent of Hurt, a graduate student at TCU, but also proof of the influences of Francis Bagley, for whom Hurt was an assistant.

Jenny Schlief’s To the Lady Saying Hush weaves pornography, stuffed animals and the pyrotechnics of video and blinking lights into an in-your-face moving image tour de force. Wearing rabbit ears, the black face paint of whiskers and a nose, and fake über-eyelashes, Schlief gets in bed, puts her hands beneath the covers and strums herself to sleep. As she pleasures herself, she repeats “goodnight moon,” the title of Margaret Wise Brown’s children’s book from 1947. The video monitor sits in the center of a mound (wink, wink, nudge, nudge) of flashing-eyed stuffed bunny rabbits. On top of the monitor are ceramic bunny tchotchkes. The piece elicits combined emotions of voyeurism and shame. But is it feminist? The question begs.

In Thomas Müller’s Pea with Giraffes , we find pastel pink minimalist pedestals with five tiny, misshapen pink porcelain giraffes and one pea dispersed on top. On the wall in front of the small installation is a large photograph focusing in reverse order on the pea and giraffes. The real pea on the pedestal is dry and shrunken, while the pea in the photograph is robust and ripe, looking like a Granny Smith apple. Three-dimensional and two-dimensional space meet in a face-off. Though this piece is powerful in form, its concept is not altogether clear. Is this a critique of minimalism? Does the play between the fresh pea in the photograph and the shriveled real pea mean that Müller is interested in capturing the passage of time? Or does the dialectic of photoplay and real sculpture mark a statement on the omnipresence of the copy? Because the idea doesn’t emerge clearly, Pea with Giraffes remains, rather titillatingly, in the realm of decorative form. This is not to say that this sculpture-photo piece must be conceptual in order to succeed. It is to say, however, that if this work is without a point, then it becomes a sculptural sketch for IKEA.

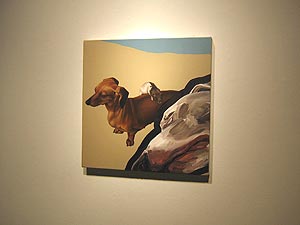

The one small painting by Raychael Stine, You Are Not Alone in the Light , leaves you wanting more. This painting mixes figures and painterly blobs in a space that pushes to expand beyond two dimensions. In it we find Stine’s dachshund, Pickle, with a mouse on her back, adjacent to a dense cloud-like form of dark-hued paint. The juxtaposition of animal form and abstraction creates a tension that is strikingly in keeping with the show’s theme of “feral nature.” It makes that theme suddenly all about painting’s willful pollution of itself. If only there were more paintings here by Stine, and bigger ones at that.

Claire Cowie’s drawings of animals are stark and peculiar. Her dream-like The Ruins depicts an upside-down turtle atop detailed patterns of cell-like forms. Cowie combines deflated organic geometries and wild animals as if to create a Genesis myth based on nature’s loss. Her vestigial markings on paper tell us that in the beginning there was a world of odd-body flora and fauna.

John Byrd’s Untitled, Western Narrative deconstructs the art of taxidermy and the myth of the Wild, Wild West in one fell swoop. A shirtless cowboy-squirrel lies wounded, entrails oozing out of his chest, in front of a torn-apart wagon. Instead of wearing a cowboy hat, however, the squirrel’s head is preserved in a hermetically sealed glass thimble.

Karen Davenport’s room of tiny photographs and prints succeeds in image but fails in organizational form. Titled Self Preservation , the installation is made up of many small photos and ink-jet prints pinned delicately to the wall. We see distorted images of the naked artist, small urban scenes, carcasses of birds and dogs jumping in midair, all mounted in a straight line on the wall. The orthogonal organization of the images makes the piece seem too controlled. The order, in turn, plays up the work’s overall preciosity. A little chaos would make the piece more powerful, not to mention more in keeping with the idea of “feral nature.” Ultimately, the installation reads like wild, off-the-hook dreams that have been ordered, domesticated and recorded in space.

Will Rogan’s Getting Through Spectrol Vortex, a video of his daughter dancing with many reflections of herself made from folding mirrored panels, replays Jacques Lacan’s essay “The Mirror Stage.” It is cute and almost funny, but out of place here.

The great strength of this show is its attempt to break up the straight face of reason by letting loose the high-jinks of the animal within ourselves. Idea strong, Feral Nature at the same time does not neglect form. There is a distinct kind of rough-and-tumble formal language in many of these works, even as each piece is different from the last, and this polymorphism creates a legible seamlessness in the exhibition.

1. Keynes, John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 1997), 161-63.

2. Lippit, Akira Mizuta Lippit, “Magnetic Animal: Derrida, Wildlife, Animetaphor,” MLN , Vol. 113, No. 5, Comparative Literature Issue (December, 1998): 1111- 1125.

3. Sloterdijk, Peter Sloterdijk, Critique of Cynical Reason, trans. Michael Eldred (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 101.

Images courtesy the artists.

Charissa N. Terranova is an Associate Proffessor at SMU and a Contributing Editor to Glasstire.