he Socrates Sculpture Park is located in Long Island City, Queens, overlooking Upper Manhattan across the East River. It is relatively difficult to get to…

Karyn Olivier... It's not over 'til it's over... 2004... Socrates Sculpture Park; 14 feet x 24 feet diameter

The Socrates Sculpture Park is located in Long Island City, Queens, overlooking Upper Manhattan across the East River. It is relatively difficult to get to; the fifteen minute walk to the park from the train runs along a busy commercial street, past an evangelical church, near a high school with large playing fields, and across an intersection into what seems to be a dead-end, but which eventually opens up into the Park itself. It is important to understand the physical context of the park: how it is situated far away from but with a view of Manhattan, how it feels very much like a place that is separate from but proximate to a very real “neighborhood.” The park is a destination, but also a kind of noplace — even the view of Manhattan doesn’t read: the skyline one would expect is south of the Sculpture Park: all we have here are tallish buildings on a river. It could be anywhere; or rather, it could be across the river from anywhere.

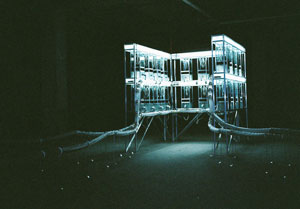

Karyn Olivier uses this sense of displacement to good advantage in her piece It’s not over ‘til it’s over (2004), which is located in the middle of the large central field of the park (with other large sculptures from the Emerging Artist Fellowship Exhibition hulking around edges and in corners in the background). It is a recreation of an amusement park carousel, 14’ high and 24’ in diameter, slowly and silently rotating clockwise. Painted plywood makes up the floor and base of the structure, which is supported by a welded steel framework. Above the circular platform, a ring of red and yellow painted curved plywood forms the bottom ring of the carousel’s “roof” made of a fitted, blue vinyl tarp. The whole structure is topped with a single red and yellow pennant, which completes the overall impression that it is a carousel made using a child’s drawing as a plan. Instead of the usual carved horses and sea monster benches, there is a single 60s-style school chair, made of plywood and metal tubing. This lone chair faces left, in the direction of the carousel’s unconventional clockwise motion. The carousel slowly turns, bringing into view the other sculptures (unamusing “rides”) and the occasional glimpse of the anonymous skyline, the industrial buildings on the other side of the Park, the welding sheds of the sculpture studio. On a sunny day, with a sweet wind blowing and the park filled with people, this trip might be a delightful one: President of One’s Own Carousel Ride surveying the domain, finally having gotten what one always wanted as a child (and still does): the only seat that everybody wants.

But on the day that I went to the park it was dark and misting slightly; the only other person there was a gruff old man running his dog. It felt like I was taking one last ride at the end of the world: the single seat becoming sinister, as if there was no one else left to sit on the carousel but me, going around and around in eerie silence through the bleakness — the happy colors and cheerful iconography of the carousel overwhelmed by its own DIY construction and the cheerlessness of the park. Olivier creates a psychologically charged context that taps into the emotional and memory responses of her viewers. It’s not over ‘til it’s over is well-incorporated into its strange, parkish setting; and as the conditions of the Park change, so too will the conditions of the piece. This sense of flux between environmental context and constructed object combined with the emotional cues built into the object give Olivier’s best work a sense of formal rigor and ontological poignancy without precluding contradictory readings.

Karyn Olivier ... Winter hung to dry... 2004... Artist's winter clothes and clothesline; 7 x 80 x 30 feet

Winter Hung to Dry, originally made for a raw warehouse gallery space while Olivier was getting her MFA at the Cranbrook School of Art and Design, felt less at home at the Triple Candie Gallery in Harlem. Triple Candie is a very long space divided into three bays separated lengthwise by rows of columns, with Olivier’s work in the center bay. The piece itself is comprised of a single, 75-foot steel cable attached to the walls on opposite ends of the gallery 6 feet off the ground. On the center of this industrial clothesline is a giant pile of the artist’s clothes. The clothes are youthful, heavy on the knits and bright colors, with one ancient merino sleeve grazing the floor. The clothes are all massed together in the middle, pod-like, stacked vertically rather than wrapped or pushed together horizontally along the line. This massing feels counterintuitive, evocative of a body lain across a steel mandoline — a kind of violence which seems incongruous with its own iconography. The piece connects with the surrounding gallery space only insofar as both are “outside dogs” brought indoors. Because of the proximity of the installations flanking the clothesline, Winter Hung to Dry is forced to become an object rather than allowed to be a catalyst for an understanding of physical/spatial context in the manner of It’s not over ’til it’s over.

Olivier’s work is at its best when it is site specific, when particular situations of location are exploited to narrative effect. It’s not over ‘til it’s over, for example, forces us to think about context not only in terms of it’s relationship to sculpture, but also its relationship to the our own physical bodies and the body of our history. It induces a kind of physical nostalgia, for good or for bad: how one’s body felt, for example, the last time one saw a clothesline used, the last time one rode a Carousel.

Images courtesy the artist and the Socrates Sculpture Park.

Nathan Heiges is a writer and artist living in Brooklyn.