In 2002, when Crate & Barrel began selling framed Rothko prints for $499, one could safely say that color-field painting had saturated the market, as it were.

Over the years, the most warm and fuzzy faction of Modernist painting lost the interest of painters, critics and academia. So goes our consume-and-toss culture. So it is with great confidence that Gallery Sonja Roesch presents One Color Only?, featuring a healthy batch of contemporary painters (and sculptors) you might call color revisionists; artists who transgress the old-way orthodoxies through a heightened sense of their making process. Here, mid-career international artists and some young up-n-comers from Houston prove that color (along with the finish fetish) is not only not dead (again), but that the ideas involved and the enduring visual pleasure they give have been renewed by the endlessly diverse possibilities in painting.

Take Mario Reis’ river works for example: two cotton panels that have been submerged in two muddy rivers in two different regions of the world (one in Japan and the other in El Nogal, Mexico). With silt for paint, the means of production infuses the delicate panels not only with organic tonalities, but with a sociological commentary and a specific, geographic reference too. Peter Willen’s untitled series of egg tempera-on-cotton monochrome pieces (in primary yellow, green and blue) also explores a new type of texture, though the paintings are made using a classical method. The small-scale pieces are laboriously multi-layered up to a surface that resembles wooly Muppet skin.

Established German sculptor Herbert Hamak is represented by a honkin’ chunk of resin that glows, as the daylight changes, with a strawberry viscosity. Like Hamak, Thomas Vinson’s work typically embodies a more voluminous kind of installation, but here, the artist (trained as a sculptor) goes all Malevich on us with white-white stripes – an attempt to corrugate the canvas’ surface in two dimensions.

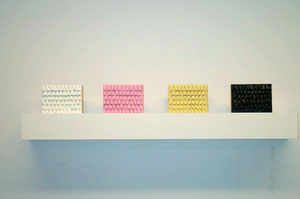

Whoever said color is non-representational can kiss Melanie Crader’s Classic Cut, a curved indigo panel with a subtle racing-stripe gesture down the side that harkens back to Brooke Shields’ booty, circa “Nobody gets between me and my Calvins.” Crader’s reductive forms benefit from the rigor and precision of her designer approach, which is also evident in her series The Ruffle (featured in the classic clutch) – four wood blocks onto which a fluffy, girlie fringe is fused and then frozen by a heavy coat of pastel paint. Together, the four different colored “Ruffles” look like tiny handbags, set away from the rest of the show on a shelf as they might be displayed in a boutique. Mick Johnson, last seen in Diverseworks’ Texas Prime group show, uses different fonts like a painter uses various brush strokes. He has two pieces here, one in Arial (black piece) and one in Fancy (blue piece).

But the real show-stealer is Thomas Deyle’s Scarabaeus series. Each panel consists of 600 rolled-out, micro-thin layers of acrylic paint on acrylic glass film. The surfaces of these three pieces dissolve into murky, minty vapors. They’re enticing like a mirage, elusive because you can’t look at them without looking through them. Watch out for Deyle’s own solo show here in a few months, with whole-wall-sized works.

Southwesterner Alan Ebnother keeps a cool finish fetish vibe alive with his unwavering richness of texture and strict production rules (everything he does is green). His January 20th, 2004 gives tiny indicators of its pink underlayer, peeking out from beneath mossy-colored smears that have the consistency of cake frosting. Shawn Wallis’ red painting exhibits the artist’s perfect sense of uniformity and surface space (a classic skill for dichromaticist painters). But British-born Alma Tischler’s ode to mono, Black Mirror, pokes out from the wall unsettlingly, like a tightly pulled black vinyl corset. With evidence of multiple paint layers dripping at the sides (but smothered in black acrylic otherwise), it’s a veritable kick in the teeth to formal field painting conventions.

Images courtesy the artists and Gallery Sonja Roesch..

Wendy Gilmartin is a writer and designer living in Houston.