For all their physicality, Ken Little’s newest sculptures project a fragile monumentality.

Over a thirty-year career Little has assembled sculptures from clay, found objects, and bronze. Now he has turned to a ubiquitous, instantly recognizable material — the American greenback. The dollar is our basic economic building block, the currency equivalent of a brick, and Little plays on his ceramicist past by stacking the bills, back and front in alternating rows, in the same way that a mason would construct a wall.

Remove the printing and these sculptures are paper-mache over wire and metal armatures. But by embracing this instrument of commerce’s intense symbolism, Little animates the punning, self-deprecating, satirical sensibility that is one of the best parts of his art. The exchange between physical form and symbolic substance gives Little plenty of room to maneuver.

A life-sized suit, Pledge conflates the promises politicians make in exchange for money, their deprecation as "empty suits," and the adage "the suit makes the man." There’s humor here, to be sure, but it is barbed, like a hook. More recent pieces monumentalize clothing forms. Oz (a giant pair of men’s pants, for the true "buckaroo"), and Miss (a one-piece swimsuit for the well-proportioned giantess) hover off the ground, suspended by wires or mounted discretely on metal stands. Other works, like Bird and Father, are figure fragments. Bird depicts the middle finger as it transmits another universally recognized symbol. Little segues the expletive "flipping the bird" into an homage for two of his heroes, sculptor Constantin Brancusi and bebop saxophonist Charlie "Bird" Parker. Standing seven feet tall, the taut verticality of this monumental finger emulates the formal purity of the former, while the descriptive variability of the dollar bill patterns evokes the musical embellishment that was the heart of the latter’s improvisation.

Ken Little, Burn (detail), 1985... shoes, bible pages, dictionary pages, mixed media... 72 x 26 x 46 inches

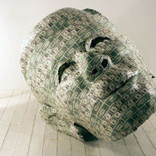

Father is different. This giant head lies on the ground, and reads like a giant archeological relic. Little describes this male portrait as a (con) fusion of the faces of recent presidents, an all too-human hybrid that "cheapens" the classic portrait of our founding father. However, the artist’s features are also present in this head, and they encourage an alternative reading of this iconic sculpture as an ironic self-portrait.

Suspended above the ground by minimal supports or entirely lacking pedestal references, other works from this series expose a sculptural interiority, even as they emphasize and magnify exterior façade. This constant juxtaposition between outside and inside embodies contradictions between vulnerability and authority, utility and beauty. It also reinforces metaphoric associations with shells, veneers, skins — vessels and containers that have long served as Little’s models for distilling or streamlining generic forms to serve particular meanings.

Burn (1985) also relates a solitary standing figure to a symbolic pedestal, but this time it is a leathery combine, strikingly resembling a bear, fashioned from all manner of ruddy leatherwear. Prefiguring Little’s dollar bill works, this bear stands atop an upturned car carapace composed entirely of dictionary pages; a small paper house, composed of pages from the Bible, sprouts from its shoulder. The next bear included in the show was made only three years later, but it shows Little in a completely different mode, working in bronze and streamlining, stylizing, and fetishizing the energetic messiness of his earlier sculptural approaches. If Burn is redolent with the smell of smoking wires caused by too many associative switches being thrown simultaneously, Bear (1988) projects the aura of a relic from an archaic ritual. It seems instantly old, votive, and valuable, like a performance mask belonging to some long vanished woodland tribe.

The distinction between these two takes on the same subject gets to the heart of Little’s artistic approach. Little is a dedicated amateur musician, and like another southwestern artist-cum-musician, Terry Allen, musical theme-and-variation figures prominently in his work. But while Allen’s musical musings always embellish the narrative shape of his predilection for storytelling, Little’s approach nuances the mutability of structure. His forms evolve, and as they change, different values can be associated with them. While riffing is not a term often associated with sculpture, Little’s best art riffs the meaning of particular forms into dozens of associative metaphors. In this sense, his restless inventiveness and insistent, almost anxious craftsmanship reminds me most strongly of the nonmusican H. C. Westermann, who composed his own flamboyant sculptural universe and then invited the world to see it on his terms.