The action in Chas Bowie’s still lives exists in-between the pictures and their sentence-long titles: there’s a gap which the viewer must bridge by imagining a story, like those psychological tests where the doctor shows you a picture and asks “What happens next?” For example: a bald flash snapshot of a shelf of art books in a cheap apartment is titled Since he was a child, he had at least a dozen cats and they had all been named Minnew.

Mini-blind cords in the foreground are literally left dangling; waiting for the cat to complete the scene. Unlike traditional photographs which clip single stills from the movie of life, (hence the verb “take,” as in “take a picture.”) Bowie uses his images to construct fictional stories with self-conscious artifice, like a stage play made entirely of sets and narration in which one must imagine the actors and dialog. Bowie succeeds in making understated, but compelling drama with such limited means, portraying vignettes from an arty, low-budget life with autobiographical compassion and immediacy.

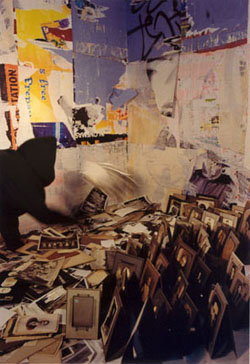

Jacinda Russell’s trash-filled interiors are rifled by blurred anonymous figures, suggesting, a furtive sifting through post-apocalyptic trash. In Detritus, crushed cigarette packs are heaped in an unfinished attic like last year’s nuts in an old sqirrel nest; another photo shows a bathroom clogged with old newspapers. In Hoard, this unhealthy accumulation becomes pointed: a grafitti-bombed basement is knee-deep in old photographic portraits.

Anderson Wrangle’s psychological interiors suggest the chaos eddying beneath the superficial order and propriety of suburban life. The wittiest are the most understated: In Untitled (lifesaving) a woman slumps on a white sofa, reading. Her head is sunken beneath the sofa’s back; she is unaware of a man we can see walking away in the window above her head.

Her book: “Lifesaving and Water Safety.” In Untitled (leaves/rocket) a comfortable TV room is invaded by fallen leaves which have blown through a door left open to the weather; the TV is on, showing an image of a rocket launch. There’s a powerful sense of abandonment, the comfort of the home shattered by violence, the aftermath of an ugly divorce, home invasion, or alien abduction. Untitled (red ball) and 4 a.m.are less subtle, resorting to overtly surreal spectacle.

Eric Zapata inserts himself into familiar mass-media images from the 80’s by standing in front of the screen in a white sweatsuit like an attention-grabbing kid. It’s a pathetically crude technique, cleverly used to highlight the pathetic yearning we all have to be the person on the screen. In Zapata’s earlier work, he dressed up to parody stereotypical Hispanic types, trying on those identities like Cinderella’s glass slipper, to see if they fit. Although this new work can also be read along ethnic lines (Zapata’s dark, adult face is pointedly not the white suburban kids from E.T. and The Breakfast Club whom he’s trying to impersonate) there’s a broader contrast: not only isn’t Zapata white, he’s not young, not a movie star, and his butt’s wider than Bruce Springsteen‘s. His grainy, anti-aesthetic pictures focus attention on the way identity is shaped by the media, and how, though we’d all like to be like Mike, we can’t.

Bill Davenport is an artist and writer from Houston.