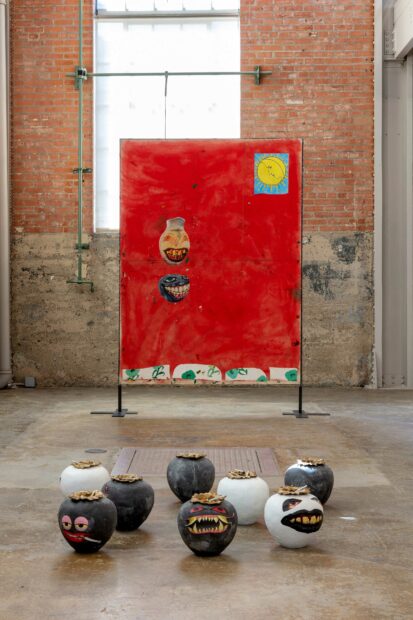

Installation view of “Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase” at the Power Station, mezzanine. Photo by Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Power Station.

At the Power Station, Paulo Nimer Pjota presents a suite of paintings, cast objects, and vases. Downstairs, seven monumental paintings converse with each other, suspended against metal frames that stand in relief. The paintings are large, and imposing, and loom over the viewer at heights of nearly seven and seven-and-a-half feet. Some are dotted with cast objects that sit below them, including gourds and bulbous feet, or bronze objects that stand in front of them. Upstairs, two more paintings are hung flush against walls, and the floor is strewn with ceramic vases that recall the amphorae that populate many of the paintings downstairs. They read like ancient Greek funerary vases for a contemporary age, updated with candy-colored shells and sticker symbols of youth (skate) culture, including marijuana leaves, Bob Marley, and smiley faces.

Paulo Nimer Pjota, “Teeth Showing,” 2020/2021, oil, acrylic, synthetic enamel ink, pencil, and pen on canvas and metal sheet with bronze object on metal support, 79 1/8 x 100 3/4 inches (left) and “Todo império quebra como um vaso [Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase],” 2020/2021, oil and acrylic on canvas and metal sheet with bronze object on metal support, 81 1/2 inches x 98 inches (right). Photo by Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Power Station.

Installation view of “Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase” at the Power Station, ground floor. Photo by Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Power Station.

The standing paintings beckon the viewer in a way that traditionally hung paintings and vases do not. In their placement off the wall, the paintings encourage viewers to walk around them, to engage with their materiality and their objectivity, much like viewers typically interact with sculpture. In these interactions, the viewer can see the recycled metal plates that back the paintings and form the standing structures. These plates — and thus these standing paintings — communicate with the industrial nature of the Power Station in a way the hung ones do not; this feels significant given the venue’s emphasis on site-specificity and fidelity to the aesthetics and history of the space.

The smaller cast objects provide a scale shift and act as a counterpoint to the paintings. Swollen three-toed feet, mostly arranged in pairs, rest below a black painting of pumpkins, a crescent moon, and bats. Eight hybrid gourd-vases-cum-ashtrays sit some yards away from a bright red painting. Some of the gourds gaze out at the viewer with comically monstrous faces, while others look back at two similarly anthropomorphized vases in the painting. These cast objects, made of porcelain, resin, and bronze, are rendered at roughly the size of actual feet and gourds. Their smallness, in comparison to the standing paintings, both reinforces the monumental size of the paintings and reminds the viewer that the paintings are in fact paintings, and not sculptures. The interplay is nice, as it forces viewers to look down and look up, to simultaneously be aware of what’s at their feet and what’s standing in front of them. This relationship also animates the standing paintings: much like the objects sitting in front of them, they can be easily anthropomorphized. They stand not on a base, but on two feet, and feel like sentinels, or room dividers we can rearrange for privacy.

Paulo Nimer Pjota, “Paisagem com lua e sol do tarot [Landscape with Sun and Moon from Tarot],” 2021, oil, acrylic, and tempera on canvas, 82 1/2 x 61 inches (background) with Cinzeiro #1-#8, resin, porcelain, and bronze, 10 1/4 x 9 1/2 inches each (foreground). Photo by Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Power Station.

The title of the exhibition, Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase, is telling of Pjota’s interest: artifacts and symbols of antiquity, and how they both collide with and are present within artifacts and symbols of the present. In one painting, titled Personagem mitico verde [Green Mythical Character], a Medieval sun, ceramic leopard head, and two severed feet are in the foreground and against a grass green background. One foot is adorned with a tattoo of a yin and yang symbol, while the other shows the face of a lazily grinning, gun-toting clown. The anthropomorphized sun, lifted from a 1493 woodcut, looks across with pursed lips at the leopard head that sits just above the feet. The disembodied leopard head and feet create a strange approximation of a whole, with both leopard and clown tattoo posing openmouthed, teeth menacing. Around the figures, scribbled bats flit, wildflowers grow in patches, and a Tinker Belle-esque bug fairy powders her face. Small strokes of primary color dot the canvas, and a red and orange checkerboard pattern across the bottom highlights the unprimed canvas at the top.

This painting, like the other works in the show, is about symbols: how they are removed from their original contexts and used in the service of new ends, how they can hold multiple meanings. The Medieval sun, a representation of light and truth, was used as a herald to justify the monarchies of Edwards II and IV of England. It is used on the Argentine flag to invoke a sense of fate, and the bright sun that illuminated the first large demonstration for Argentine independence in May of 1810. The yin and yang symbol, prominent within Chinese cosmology, has today been divorced from its roots and appropriated within mass Western culture to represent balance, light versus dark, and the martial arts, and has become charms on a bracelet or the first tattoo of a teenager.

Paulo Nimer Pjota, “Personagem mitico verde [Green Mythical Character],” 2020/2021, oil, acrylic, and tempera on canvas, 82 1/2 x 62 1/4 inches. Photo by Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Power Station.

Pjota’s work deals in the repetition of visual imagery, from antiquity to the present. His paintings feel disjointed because of the range of symbols he uses; yet there is also synthesis. Somehow, images from antiquity don’t feel anachronistic sitting next to cartoon images pulled from the street and the internet, and this is a testament to Pjota’s ability to find the visual rhythms and overlapping histories between images and across time. Similarly, Pjota combines old processes with formal decisions and imagery that feel contemporary. He often makes his own paints from powder and binder in a move that mimics the earliest forms of painting. He uses metal, a material used in construction for centuries, but not typically used within painting. It is this ability to reach back into the past and forward into the present, to find consensus within chaos, that makes Pjota’s show at the Power Station feel significant. Taken together, the works in the show posit a new way to understand the barrage of visual culture that we’re all subject to every day.

Installation view of “Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase” at the Power Station, ground floor. Photo by Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Power Station.

Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase is on view at the Power Station through March 18th, 2022.