Analia Saban stretches the elements of painting and sculpture so far that they start to become one another. In her hands, sculptures become paintings, and common elements of paintings are morphed topologically into sculptural forms. The notion that a painting can be a sculpture and vice versa strikes me as completely esoteric, abstract and maybe even irrelevant to anyone’s actual experience of art. Why should we care? When I read the description of the show on the Blaffer’s website, I quailed. But I went to see the show anyway, and I was surprised. Saban’s a funny artist, and I value art that can make me laugh.

A painting is usually made out of stretcher bars, canvas, and paint. So what if you take those three elements and combine them in novel ways? That’s one of Saban’s tricks. In Trough (Flesh), she has built a frame of stretcher bars, but instead of stretching the canvas tight on it and then priming it, she’s attached a primed canvas very loosely, so that there’s a lot of extra fabric hanging down in back of the stretcher bars. Then the oil paint is poured into the bag created by the excess canvas. The paint-filled canvas hangs pendulously. The paint is not visible unless the viewer walks right up to the piece. It becomes a wall sculpture; the idea of painting being an arrangement of pigments on a flat surface is obliterated. But the idea of painting being a combination of stretcher bars, canvas and paint is retained.

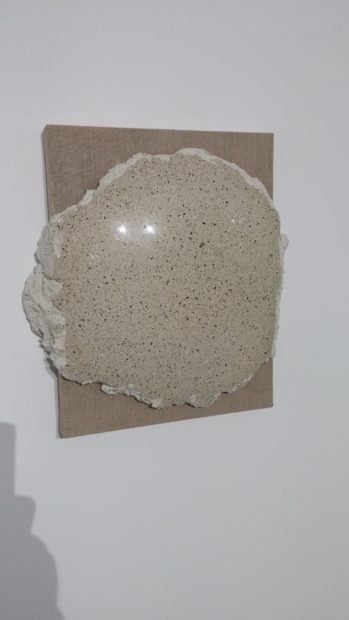

She has you asking yourself the question: what is paint, anyway? It’s basically some sticky goo that has some color in it, even if that color is just white or black. There are lots of sticky goos in the world—it doesn’t have to be some semi-solid plastic or linseed oil or wax. It could be, for example, concrete.

This “painting” is made of concrete on canvas. Just like an oil painting or an acrylic painting, semi-solid goo was applied to the canvas and allowed to dry. In this case it’s dried into a smooth, bulbous rock, becoming a relief sculpture. The fact it can easily be seen as both a painting and a sculpture is the joke. Saban seems aware of this: she named it Concrete Gag.

Saban likes to use paint as a sculptural material, as in Decant (White). Like Trough (Flesh), paint was poured into a vessel and allowed to dry there, but in this case the vessel was something attached to a canvas and then removed. What we have as a result is the negative space that was filled with liquid paint on the bottom half of the canvas. On the top half is a pour of paint that implies that’s the direction the paint came from.

Marking (from Porcelain Bathroom Sink), found bathroom sink and ground sink pigment on linen canvas, 2014

Other times Saban likes to use material more associated with sculpture as if it were paint on canvas. One is Marking (from Porcelain Bathroon Sink), in which the dust of a ground down ceramic sink is used to mark a canvas, and another is Draped Marble (Fior di Pesco Carnico, Fior di Pesco Apuano, Crema Dorlion, Onyx), in which small chunks of marble are attached to a steel armature that looks like fabric draped over a series of sawhorses.

Draped Marble (Fior di Pesco Carnico, Fior di Pesco Apuano, Crema Dorlion, Onyx), marble mounted on steel on wooden sawhorse, 2015

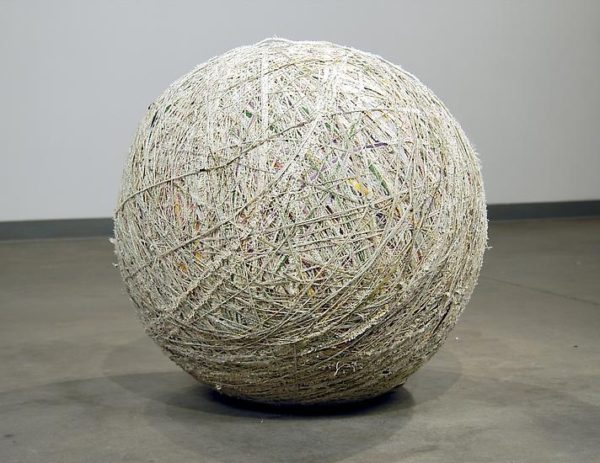

The earliest work in the show that I saw was The Painting Ball (48 Abstract, 42 Landscapes, 23 Still Lives, 11 Portraits, 2 Religious, 1 Nude), from 2005. It’s a giant ball of string, and the strings are pieces of painted canvas that have been carefully unwoven, piece by piece, then reassembled into a 26- inch diameter ball. It is kind of a heavy-handed reminder to the viewer that whatever else a painting is, it’s pigment on pieces of fabric.

The Painting Ball (48 Abstract, 42 Landscapes, 23 Still Lives, 11 Portraits, 2 Religious, 1 Nude), oil, acrylic and watercolor on canvas, 2005

The whole show is a good inside joke about what painting and sculpture are. I was reminded of work by the Art Guys, especially one of their wittiest drawings, Any of These Locations Would Be an Excellent Place to Begin a Drawing (2008). Saban’s work is a playful examination of what make up painting or sculpture, and what we expect from it. I like inside jokes—they’re often the funniest jokes of all, as long as you understand the context. And in a location like the Blaffer, I’m an insider; I’m someone who is aware of the history of art and the history of artists playing around with the definitions of painting, whether it is John Frederick Peto, Marcel Duchamp, Lucio Fontana, or Saban. But I also wonder if now, as we stand on the brink of fascism, is the time for art to be telling inside jokes.

Through March 18, 2017 at Blaffer Art Museum, Houston.