Two recent exhibitions at the Ransom Center Galleries did what the Harry Ransom (Humanities Research) Center does best. They conveniently collected together a wealth of rare or unique artifacts for public speculation: here was treasure without the hunt. No map or card catalogue was provided; the only keys to these wonders were wall text and, well, lots of it.

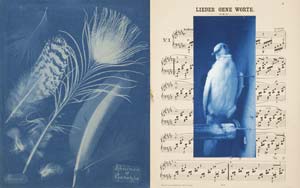

Left: William Henry Fox Talbot...Fern and Jasmine, 1839...Photogenic drawing...Right: Rebecca Foley...Still Life #56 (Clover), 2001...Color photogram/Type C print...© the artist

Together The Image Wrought: Historical Photographic Approaches in the Digital Age and Technologies of Writing mined Texas’s "finest cultural archives" and its two largest collections, selecting from 5 million photographs and 36 million literary manuscripts, respectively (a proportion mirrored in the exhibitions). But to say that there was a photo show and a text show does not really do either justice. The Image Wrought , after all, came with a glossary. And Technologies of Writing offered souvenir yellow pencils, embossed with the exhibition details, at the show’s entrance.

Each exhibition proposed to map the historical range of its chosen medium. But the search for limits produced two very different displays. Intentions were realized or not. Museological multimedia musings do not necessarily breed comprehensiveness.

, 1845…Cyanotype…Right: Jesseca Ferguson…Songs Without Words, 2000…Pinhole Ware cyanotype, sheet music, book board…© the artist”]

The Image Wrought, curated by Linda Briscoe Myers, was a tight, smart and sometimes beautiful survey of alternative photography methods. Like many of the sharp pictures on view, its attention to detail was both attentive and illuminating. Eighty plus works were pointedly arranged according to the generating photographic process. Vintage images from the 19th century were paired or grouped with their contemporary reprisals. A salted-paper print by William Henry Fox Talbot (1844) led into a work by France Scully Osterman (2002); stereograms from the turn of the century were juxtaposed with the recent 3-D images of Michael Radin (2002); and so on for 20 some alternative processes. It was a very didactic setup, reminiscent of the dual projectors of art history lectures, and certainly not the most evocative. But as a pedagogical tool, teasing out similarities and differences, and accelerating genealogies, the layout proved effective and clarifying. As a solution to the show’s central paradox, its success was less clear.

The obvious question under examination was why exactly someone would want to dip into the archaic and frequently toxic past to "work" a contemporary image. It was a timely investigation. The rise of digital technology has marked the imminent extinction (or marginalization as "alternative") of popular photographic processes. Kodak Corporation decided last year to cease making black and white printing paper, Nikon has halted production of film cameras, and recent years have witnessed bankruptcies by both AgfaPhoto and Polaroid. The new standard, the pixilated image, however, does not suit the aesthetic aspirations of all picture-makers.

To call these artists" response a revolt, like the anti-corporate alternative movements of the 1970s, would be misleading. The mood of the galleries was embracing or exploratory, not seditious. We learned (more from the accompanying wall texts than from the actual images) that Robert Shaler’s daguerreotypes explore the tension between contemporary image and antiquated process. Eric Renner enjoys the child-like innocence of his face-camera pinholes, and Jessica Ferguson’s cyanotypes involve the slow, hand-built accumulation of memory over time. There is a commitment to physicality, an investment in labor, but also a search for effects (some of the artists on display even hybridize, using digital negatives but finishing in "alternative" prints). Nostalgia at the foremost reeked throughout. Already photography’s bedfellow, it took on a new material intensity here.

Maybe it should not be so surprising, then, that when we compared the new to the old, the earlier images almost invariably looked better. Except for the tintype by Deborah Luster, the gum brichromate print of Adam Lubroth and a handful of others, none of the contemporary works on view matched their predecessors. The originals just looked fresher. Briscoe Myers made the contrast vivid by frequently pairing images with matching subject matter, pushing attention toward nuances of execution. The historical images, often commercially wrought, may lack artistry, but they more than make up for it in elegant attention to detail, luminescence and sheer, stunning visual gravity. By comparison, the new prints sell artistry, but their affectation seems just that, put on or naïve, amateurish even, falling into the traps — sentimentality and craft — of the nostalgia they court.

The Image Wrought clearly demonstrated the appeal of alternative processes, but left something wanting in the case for their continued use. It is a common fate of art that is embedded in technology as photography is, especially here, where that technological focus was all we are allowed to see.

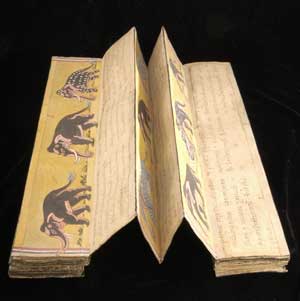

This binocular vision, however, seemed an asset when confronted with the panoramic sweep of Technologies of Writing. The exhibition proposed to "represent the global history of writing over the last 6000 years," and it succeeded by sprawling an impressive collection of tokens, parchments and books in the adjacent galleries. Yet whereas The Image Wrought may have limited itself through prescription, Technologies of Writing attempted so much, and so unevenly, that legibility became an issue.

The problem was that the show lacked a permeating and guiding organizational structure. The introductory galleries promised a geo-chronological path. The origins of writing were traced along four histories: Mesopotamian/Greek, Egyptian, Chinese and, last and least, Aztec. A field of glass-boxed tables showcased geometric tokens, cuneiform tablets, phonetic hieroglyphs and Linear B ideograms. Accompanying each were the Ransom Center’s own tablets of explanatory text — highly informative, if neck breaking in their orientation.

Somewhere along this vague spread, religion trumped geography, and sacred texts became the instructive paradigm. Gorgeous Korans, psalm books, Bibles and a Torah from Poland were situated according to faith. From here, Technologies of Writing dissolved into a series of titled, but mostly unexplained, topical explorations. "Writing as Power" followed "Cryptography and Secret-writing," and somewhere in between fell "George Bernard Shaw and Spelling Reform." Quotes by famous writers (Thomas Jefferson, Charlotte Bronte, Don DeLillo) adorned the upper walls, while paintings of writers writing (Tennessee Williams, Rabanus Maurus) and odd paraphernalia hung below. Technologies of Writing , it seems, had morphed into "Anything to Do with Writing."

At the center of the spiral, exhibition curators Kurt Heinzelman and Elizabeth Garver defined writing, most basically, as a codified system of inscribed signs. They also assigned it the role of memory and called it a defining quality of the human race — "man’s greatest invention." But, significantly, writing is an evolving invention. So they further declared that no important change to the human condition has occurred without "a corresponding alteration in how writing is produced, stored, or reproduced."

An interesting idea, but as a guiding thesis or an organizational statement, it was not carried by the show. Technologies of Writing played witness to the changes in marking and copying, but did not spell out their link to social change. A seemingly helpful wall-sized timeline, with its writing awkwardly turned sideways, only recorded dates specific to the history of writing. Moreover, for a show about technologies, there were very few writing implements or devices on view. The noticeable exceptions were a Dictaphone, a wonderful case detailing the pencil and an IBM typing ball interestingly placed amongst a few Chinese calligraphic pens. Predominantly, though, the products were presented and not the tools, so much of the writing process was left to the imagination.

What we did get was a look at some amazing pieces of literary archeology. The roster was so outstanding and diverse that at times the exhibition seemed an excuse for the center to show off its wares, but the curators actually, and impressively, culled from the university as a whole. Here in the building foyer were the center’s Gutenberg Bible, a decree by Charles V giving Cortez the Western Hemisphere and John Steinbeck’s original manuscript of East of Eden. Modern writer memorabilia especially abounded: a postcard from Walt Whitman mingled with telegraph dispatches by Ernest Hemingway; D.H. Lawrence’s seal met Edgar Allan Poe’s desk and Anne Sexton’s typewriter. Somewhere nearby was the first edition of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, also on view in Braille.

Carroll, who got double-billing with an albumen silver print in The Image Wrought, complemented a particularly remarkable section on visually oriented texts. Beautiful picture poems and calligraphic works accompanied illustrated pages by William Blake and a cowhide stamped with the hieroglyph-like brands of TX. Writing’s "Pictorial Tradition" led, appropriately, into a very intelligent comparison of webpages to illuminated manuscripts and then a final fascinating chapter on hypertextual fiction.

In the preface to this final frontier, in which writing and reading become more open tasks, the show revealed a most promising idea. Paraphrasing Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1830: Reading as well as writing should be a creative act. It is a suggestion worth taking for the entire show and assuming from the beginning. One cannot, after all, read everything that has been written.

Both The Image Wrought and Technologies of Writing detailed the documentation of memory, whether through photographs or writing systems. Like memory, the exhibitions seemed both inescapable and elusive. But they also formed a necessary and highly rewarding reflection to understanding who we are, where we came from, and where we are going.

Images courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

Kurt Dominick Mueller pursues an MFA at the University of Texas Austin.