At a recent lecture about his work at Southern Methodist University,

the artist Tony Matelli made a crack declaring all public art to be

corporate jewelry. He was arguing that most public art serves the

function of mere decoration with the added bonus of making the

sponsoring corporation or public institution seem engaged with pursuits

more noble than power or profit.

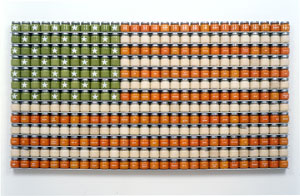

Kate Ericson and Mel Ziegler...Peas, Potatoes, Carrots...1994-1996...Etched and painted glass jars filled with baby food...aluminum shelves...364 jars, on twelve shelves...Overall dimensions 30.75x58.5 inches

Does all public art function this way? And what does the designation

“public” mean? Is it more public than work seen in museums or

galleries? Is it diametrically opposed (as the term implies) to the

private ownership of art objects by collectors? What is the audience of

public art supposed to be as opposed to audiences for other forms?

America Starts Here, an exhibition at the Austin Museum of Art (AMOA) about the 10-year collaboration between Kate Ericson and Mel Ziegler,

begins to ask some of these questions. The work shown here lies at an

intersection of vectors of art, politics, social justice, marriage and

mourning. And as such it adds to these questions even more puzzling

issues that plague the museum as an institution. More on that later…

Ericson and Ziegler met in 1976 at the Kansas City Art Institute

where they were both students. Their first collaboration was a thesis

show involving coal chutes that referenced the mining interests of the

main benefactor of the building in which the exhibition was held. This

work points toward later work that continued to develop methods of

revealing monetary and social exchange in a given community.

They moved to Houston for a couple of years, then in 1979 went to gradate school at Cal Arts. There they met Michael Asher, Douglas Huebler and John Baldessari. This was a moment of crystallizing vision in which they both began to see their relationship to artists such as Robert Smithson

and Gordon Matta-Clark. They were interested in the site-specific

strategies that these artists used to engage landscape in their work,

but were wary of the aggressive and relatively obscure nature of those

artists’ approach.

In

1982 they moved to New York City, where Ziegler worked for Dan Flavin

for a time. In 1985 they decided to work exclusively as a collaborative

team. They continued to work together until Ericson’s death in 1995.

An early piece, If You Would See the Monument Look Around

(1986), illustrates the way that their projects sought to avoid the

monumentality of public art and how they used their projects to frame

the communities in which they worked. Ericson and Ziegler were

commissioned by Creative Time and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

to make a piece about Central Park. Rather than construct a large

sculpture that would add to what was in the park already, they decided

to make a piece that emphasized the park as a living thing.

They collected the tools used by the Central Park maintenance crews and

coated them with bronze paint. They then returned them to the park

workers to use. Cards were handed out to the public, encouraging those

looking for art in the park to look for these tools. As a result, the

paint framed the tools as instruments of labor. This emphasized the

park as a work of art — a constructed manifestation of culture rather

than an aberration of nature.

Curated by Ian Berry of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and Bill Arning of the MIT List Visual Art Center , America Starts Here

is a conceptual exercise in itself. The physical objects in the show

function as placeholders for a much larger matrix of information.

Kate Ericson and Mel Ziegler...Statue of Liberty...1988...Five etched glass jars filled with latex paint on shelves...57.5x5x5 inches

Some work seems uncomfortably crammed into the office space that is the

AMOA. A couple of video screens show slides of Ericson and Ziegler’s

site-specific projects, pointing outward to work that couldn’t possibly

be recreated for the show. A model of Camouflaged History

(1991) acts as a stand-in for the actual house painted in a camouflage

of historical colors, Confederate gray and Yankee blue, in South

Carolina. In addition, the accompanying catalogue to the exhibition

provides a great deal of illuminating information about projects

unrepresented in the galleries.

A walkthrough with Berry, Arning and Ziegler, which was open to the

public, was invaluable for giving context to the work. Each piece has a

story, and like a good deal of conceptual work, this art does not

function on its own. It resists the autonomous qualities of work that

relies on an aesthetic superstructure. As each story was told, the work

opened up to reveal multiple layers of thoughtful intervention, and as

a participant I felt as if I were seeing the work for the first time.

The title piece of the show was made for an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA)

in Philadelphia. Ericson and Ziegler found a warehouse in Philadelphia

in which a homeless person was living. They removed all of the broken

windows from this building and replaced them with new ones. They

brought the broken panes of glass and installed them at the ICA in the

same configuration that they had found them, sandwiching them between

sheets of glass sandblasted with trails, canals or cracks found in

former or current national capital cities like New York, Philadelphia,

and Washington, D.C.

As a result, this piece becomes an intersection of references. It alludes to Marcel Duchamp’s famously broken Large Glass, which resides at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, to the cracked Liberty Bell, also in Philadelphia, and to the geological fissures that serve as points of connection.

The ICA show was, in some sense, in two locations at the same time. The piece America Starts Here coexisted in both the gallery space and the gutted warehouse of the National Licorice Company

factory at 1301-19 Washington Avenue. One was the negative of the

other. America itself could be said to start both in a place of

cultural innovation and in the decayed husk of an emptied-out

industrial past. In its AMOA manifestation, America Starts Here

has slightly less power — referring to the dualism of the Philadelphia

iteration, but lacking relationship to Austin as a place.

In some ways, though, the AMOA show as a whole does have an external referent in Austin: The University of Texas

where Ziegler is an associate professor of sculpture. Ziegler’s

engagement with the Austin community as a teacher serves as the element

of public involvement that hides under the surface of this exhibition.

But as is true for artists anywhere in America, the primary signifier

to which we all turn, like Mecca or the Wailing Wall, is New York. And

the holiest of holies that sits at its center is The Museum of Modern Art.

One of the best pieces in the show is almost invisible. MOMA Whites,

1990 is being shown for the first time at the AMOA. The story behind

the piece begins with research that Ericson and Ziegler did when they

were invited to participate in MOMA’s Projects series in 1987. They

found out that each of the major curators had specific shades of white

that they preferred for their exhibitions. So each wall in the AMOA has

been painted with one of these shades of white, revealing the

instability within the edifice of the modernist white cube and the

false autonomy of its space. It reveals the museum as a community just

like any other, with conflicting opinions and histories.

Walking through the exhibition, I was struck by the question of

accessibility. One of the interesting aspects of Ericson and Ziegler’s

approach to public art is the way that it manifested in places ranging

from MOMA to a sidewalk in Durham, North Carolina. Their work reclaimed

museums as public space for art, while it framed innocuous public

spaces as artworks in themselves. This allowed anyone to participate in

art — a practice that many in America view as elitist.

But how can a public that still thinks of Claude Monet and

Impressionism, of painting and sculpture and figure studies, as the

highest, if the not only, forms of art begin to approach a cupboard of

dishes, a pile of wood scraps or jars of paint as art? How can they

move past the broken glass to see the complex intersection of

references?

These are the big questions for conceptualism. They have particular

resonance within public art as a practice, where the rhetoric is so

democratic in its intent. The question of accessibility also plays a

big role in museums at a time when museum education departments around

the country are getting more money and resources than the curatorial

staff.

I don’t think that Ericson and Ziegler’s work is accessible to the

masses. But that’s okay. It is our job (and I am saying this as a

member of the masses) to look at not only an object but also its

context. Isn’t this the goal of much of the work in America Starts

Here? We are being asked to look beyond our assumptions and see a

broader social structure with competing claims of authority. We reclaim

our agency through this process and as a result realize that America as

a place of radical democracy starts at the point where authority is

questioned. America starts in the place where the gardeners of Central

Park and the construction workers at MOMA are the artists. The show’s

title declares what we might think to be a definite point, but it’s

not. America starts where? Wherever we are when we ask the right

questions and find that we are always — already — here.

Images courtesy AMOA and Mel Ziegler.

Noah Simblist is an artist and writer currently living in Dallas and Austin. He teaches at SMU.

1 comment

there are a couple of points in your essay that directly contradict each other. first, the assertion that the masses (whatever the hell that means). are not able to comprehend ziegler and ericson’s works very much contradicts what i can only assume ziegler and ercison themselves would say about the public. i doubt that they just demanded the tools from the maintenace crew of central park, saying “we’re artists give us your tools we need to do something with them that you won’t understand.” i’m sure they discussed the project and the idea behind it with them before they painted their tools. the fact that at least some of the workers agreed to let their tools be used in this project shows not only that they understood the project but that they enjoyed it. the discussion and the exchange of ideas and information is really the point anyway even with intellectuals. there aren’t too many people out there that can just look at a complicated piece of artistic social commentary and just comprehend it by osmosis. as you said, “context” is required.

its a pretty gross inaccuracy to say that most non-mfa holders think that claude monet and impressionism is the the height of, or the only, art. people are pretty sophisticated even if they don’t act like it. actually, i would venture the idea that most people today recognize that art encompasses a huge variety of objects and activities.

its the public artist’s (or any artist’s) job to create objects that encourage and allow the viewer to move beyond the surface appearance of things and begin an investigation. if the objects or activities that make up public art don’t spark interest in the public then it’s the artist’s fault (especially the artist who thinks of the “masses” as their audience). people don’t like to be preached to unless you’re offering them something really good like an afterlife and most art let alone most “public art” is incredibly preachy and condescending.

i could go on. just seems to me there are a couple of pretty fundamental problems in some of the statements you’ve put forth. your essay is pretty good when it describes and discusses the personal histories of the artists and the projects themselves but your philosophical framework at the end seems convoluted.