Earlier this week, the Supreme Court ruled that a 1984 artwork by Andy Warhol, depicting the musician Prince, infringed on photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright. Mr. Warhol’s silkscreen piece used, as source material, Ms. Goldsmith’s photograph she took of the musician in 1981.

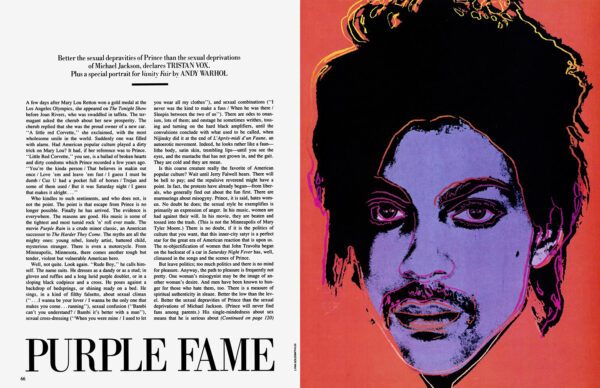

Vanity Fair, “Purple Fame,” written by Leon Wieseltier under the pen name Tristan Vox, November 1984.

Of a 16-piece silkscreen series depicting Prince created by Mr. Warhol, one particular image was at the center of this lawsuit: Orange Prince. In 1984, Mr. Warhol was commissioned by Vanity Fair to create an image to accompany the article Purple Fame, which explores the sexuality expressed in Prince’s music, and what his works’ rising sales say about society. According to the Supreme Court Decision, at the time of the commission, Vanity Fair paid Ms. Goldsmith $400 to license her portrait as a “reference for an illustration.” The magazine then hired Mr. Warhol, who used the photograph to create the silkscreen portrait. (It is important to note that artwork used to illustrate the 1984 article is not the one at the heart of the court case.) The licensing agreement required that the magazine credit Ms. Goldsmith (as seen above), and that this would be a “one time” use of her work.

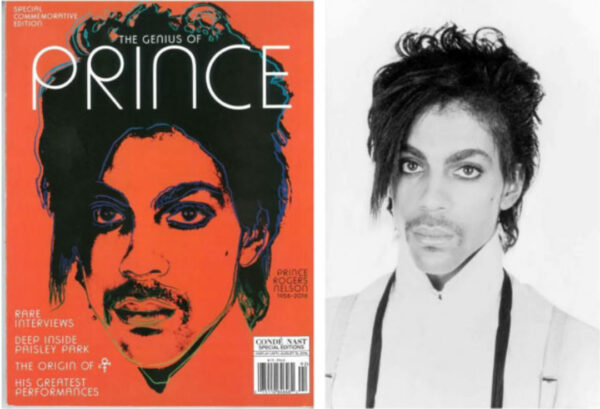

In 2016, following Prince’s death, Vanity Fair’s parent company Condé Nast reached out to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts to reuse the image from the 1984 article in an issue of the magazine celebrating the musician’s life. However, upon seeing the additional works Mr. Warhol created for the series, Condé Nast instead selected Orange Prince to serve as the cover of the 2016 magazine, and paid the Andy Warhol Foundation $10,000 to license the work. Until that publication, Ms. Goldsmith was not aware Mr. Warhol had created other prints from her image. According to court documents, she reached out to the Andy Warhol Foundation to notify the organization that it may have infringed on her copyright.

A side-by-side comparison of “Orange Prince” by Andy Warhol and Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince.

The Andy Warhol Foundation then sued Ms. Goldsmith with the goal of receiving a judgment of noninfringement, and Ms. Goldsmith countersued for infringement. Originally, the Federal District Court in Manhattan sided with the Foundation on the basis of fair use. According to the U.S. Copyright Office, Fair Use is a legal doctrine that permits the unlicensed use of copyrighted works in certain circumstances, considering whether the work’s purpose is commercial or educational, the degree to which the copyrighted work is creative or imaginative versus factual, how much of and what part of the copyrighted work was used, and the effect of the use on the value of the original copyrighted material.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the original judgment, stating that all four of the factors listed above favored Ms. Goldsmith. In the recent Supreme Court ruling, the court was only acting on a question as to whether the first fair use factor (whether the purpose was of a commercial nature or was for nonprofit educational purposes) weighed in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation. Ultimately, the Court voted 7 to 2 in favor of Ms. Goldsmith.

The Court explained in its majority opinion that, “…the first fair use factor instead focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character… As portraits of Prince used to depict Prince in magazine stories about Prince, the original photograph and [the Andy Warhol Foundation’s] copying use of it share substantially the same purpose… Even though Orange Prince adds new expression to Goldsmith’s photograph… in the context of the challenged use, the first fair use factor still favors Goldsmith.”

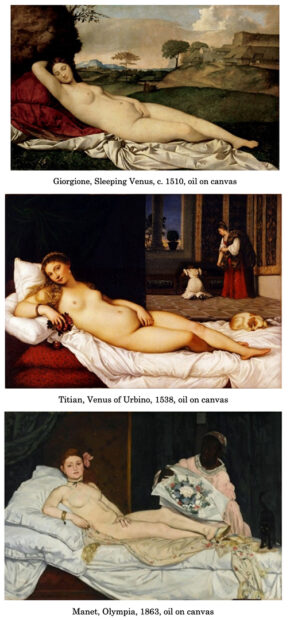

Images of paintings by Giorgione, Titian, and Édouard Manet, featured in the dissenting opinion by Justice Elena Kagan and Chief Justice John Roberts.

Justice Elena Kagan and Chief Justice John Roberts filed a dissenting opinion, which includes a few art historical references to artists using earlier works by other artists as inspiration, such as Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus compared to Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Manet’s Olympia. The 36-page dissent covers a range of considerations, though first and foremost it takes issue with the Court’s seeming indifference to Mr. Warhol’s transformation of Ms. Goldsmith’s original image.

In part, it reads, “Today’s decision—all the majority’s protestations notwithstanding—leaves our first-factor inquiry in shambles. The majority holds that because Warhol licensed his work to a magazine—as Goldsmith sometimes also did—the first factor goes against him. It does not matter how different the Warhol is from the original photo… All that matters is that Warhol and the publisher entered into a licensing transaction, similar to one Goldsmith might have done. Because the artist had such a commercial purpose, all the creativity in the world could not save him.”

Ryan Sandison Montgomery, “The Supreme Court as Andy Warhol as Lynn Goldsmith as Prince Not Laughing,” 2022, acrylic, pencil, paper, 9 x 9 inches.

In the days since the decision, many artists and writers have taken to publications and to social media to express concern over how, moving forward, this ruling will impact artists’ abilities to create original work using appropriated materials and imagery. Some artists were also feeling the possible ripple effects of the decision before it ever came down. In March 2022, Ryan Sandison Montgomery, an Austin-based artist and educator, posted to social media a mixed media work referencing the image of Prince, titled The Supreme Court as Andy Warhol as Lynn Goldsmith as Prince Not Laughing. Ms. Goldsmith responded, requesting Mr. Montgomery remove the artwork as he “did not ask for [her] permission to copy [the] photo.”

Mr. Montgomery explained to Glasstire that he is interested in parasocial relationships (relationships in which one party extends much more energy, interest, and time than the other, notably the relationships that media users or consumers engage in with celebrities), post-postmodernism, and the relationship between painting and internet imagery, like memes and viral videos. As early as last April 2022, Mr. Montgomery expressed concern over what Ms. Goldsmith’s potential win could mean for not only his artistic practice, but also the way we share images online.

Ryan Sandison Montgomery, “The Artwork Formerly Known as The Supreme Court as Andy Warhol as Lynn Goldsmith as Prince Not Laughing,” 2022, acrylic, pencil, paper, 9 x 9 inches.

Ultimately, Mr. Montgomery did not remove the post, nor was it removed by Instagram. Less than a week after his original post, Mr. Montgomery posted a similar work with a circle punched through the center of Prince’s face. He titled the piece, The Artwork Formerly Known as The Supreme Court as Andy Warhol as Lynn Goldsmith as Prince Not Laughing.

Now that the Supreme Court has ruled in the case, Mr. Montgomery told Glasstire, “I am left wondering if my practice has just technically become illegitimate or illegal. Having painted the Justices myself, I am curious how Lynn Goldsmith would suggest I capture my own references. Artists have to either ignore this ruling as the arrogance of a corrupt, unserious, rightwing majority Court, or passively enter an anti-Duchampian age, in which we instead ignore at least a hundred years of art history. Goldsmith and the majority want us to understand art’s value as being primarily in its monetary worth, but I believe art is a feeling, like love, and it is inherently communal.”

Currently, six of the Supreme Court’s Justices were nominated by a Republican President, while three were nominated by a Democratic President. The bipartisan majority opinion was authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and the dissent was authored by Justice Elena Kagan.

Diane Durant, a Fort Worth-based photographer, writer, and professor at the University of Texas at Dallas, shared her thoughts on the ruling. She explained, “The opinion that this ruling will make our world ‘poorer’ and ‘thwart the expression of new ideas’ is pure hyperbole, not to mention an insult to artists and the way they interpret the world around them. As a photographer, I appreciate the copyright protections that were confirmed in the ruling, but honestly I think this case specifically was pretty cut and dry. Of course Lynn Goldsmith deserves compensation for the second use of her source image, unless she sells it to the Andy Warhol Foundation and ownership of the image is legally transferred. It’s how photographers do business!”

Ms. Durant continued, “But as an artist, I’m not going to quit making work or quit looking at other artists for inspiration because of this ruling, and I don’t think anyone else will either. (The dissenting opinions can relax. Creativity will prevail!) Just be a good art-citizen and give credit where credit is due–or required by law.”

Mike Moffatt, a Fort Worth-based artist whose work often references images from movies and popular culture, is still wrestling with the decision. He told Glasstire, “Part of me is happy for the photography folks having more say when their work is reproduced. I can see this being a bigger problem with the corporate or fashion industry. This was Andy Warhol, a photographer! Why didn’t he take his own picture?”

Similarly, Bill Davenport, a Houston-based artist and former Glasstire Editor, explained, “I think Warhol could have afforded the licensing fee. Copyright is about money, not rights—people making money off creative work should share it equitably among the works’ creators.” When asked if he was concerned about the decision’s potential impact on his own work, in which he often references and recreates painted and sculpted versions of commercial products like canned food, books, and board games, Davenport said, “I’m not worried for my own work. If I use something somebody else made, I’ll be happy to pay them part of whatever I earn from it.”

2 comments

I’m glad our art is protected still by the US Copyright law of 1976. Don’t steal my art and then make money off it when you add some flourishes to try to hide that you stole my art. No. You stole my art, my idea and then you didn’t even offer to pay me $10 for my creativity. No.

US intellectual property rights were designed around text and print. Don’t expect a Supreme Court to know art history or its critical analysis. A person can’t own another person’s likeness simply because that person took another’s photograph. If photographers are worried about their work being repurposed or appropriated by other artists, don’t mass reproduce work in distribution everywhere. Early copyright iterations of Mickey Mouse as Steamboat Willie are finally set to expire on Jan 1st, 2024 next month. It will enter the public domain as will all things eventually. That includes insipid photographs of public figures.