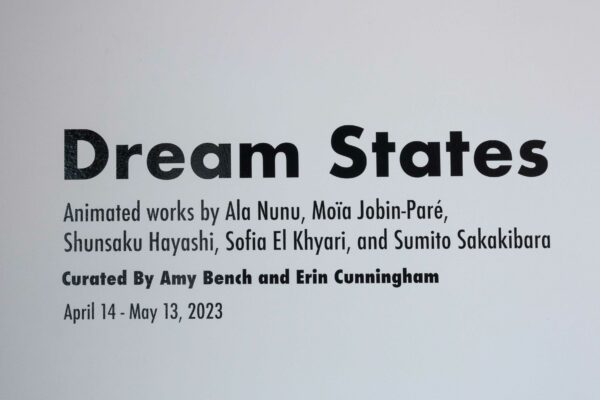

In filmmaking, animation has been disproportionately skewed toward illustrating children’s narratives. This norm perpetuates that stylizing the natural world is inadequate for exploring mature subjects, thus making animation synonymous with cartoons that only scratch the surface conceptually. Though stereotypically ignorant, that connotation persists in the collective vernacular. Many animation artists have emerged as antidotes to that reputation, and five of them are exhibiting in Dream States, a series of short animation films on view at ICOSA Collective until May 13.

Dream States not only exemplifies how animation can navigate nuances of the human condition, but it also argues there are certain niches that only this medium can access. Five films by five animation artists are displayed: L’ombre des Papouillons/Shadow of the Butterflies by Sofia el Khyari of Morocco/France; 4min15 au Révélateur/4min15 in the developer by Moïa Jobin-Paré of Canada; Ahead by Ala Nunu of Poland/Portugal; Railment by Shunsaku Hayashi of Japan; and Iizuna Fair by Sumito Sakakibara of Japan. Each film implements the figure as a subject, channeling lived experiences through the lens of the filmmakers’ animation style to construct unique expressions of universal feelings, such as desire, isolation, and existentialism.

Co-curators Amy Bench and Erin Cunningham have fused their individual artistic practices — Bench a cinematographer and filmmaker, and Cunningham a sculptor — to highlight how animation is as complex in its process as the themes it navigates. The films are installed in ICOSA’s gallery space like a 360-degree screening, with each playing on a loop. Stills from each film are displayed alongside their monitors, exhibiting the animation processes and their textural differences.

Sofia el Khyari’s L’ombre des Papouillons/Shadow of the Butterflies begins the film sequence in ICOSA’s front window space. Khyari guides viewers through the protagonist’s disorienting daydream as she journeys through the forest while observing butterflies. Shadow of the Butterflies is composed of watercolor paintings, six of which are also on display. The fluidity of the watercolor brush strokes morph butterfly wings into the woman’s lips, and her fingers into dangling chrysalises. Paired with a breathy soundtrack consisting of whispered wing flaps and moans, the viewing experience is sensual. Once the woman comes out of her daze and settles into a moment of clarity, I, as the viewer, feel like I’ve just come down from a mushroom trip — tired from heightened senses, but blissful.

Sofia el Khyari’s “L’ombre des Papouillons/Shadow of the Butterflies,” on view in “Dream States” at ICOSA. Photo: Caroline Frost

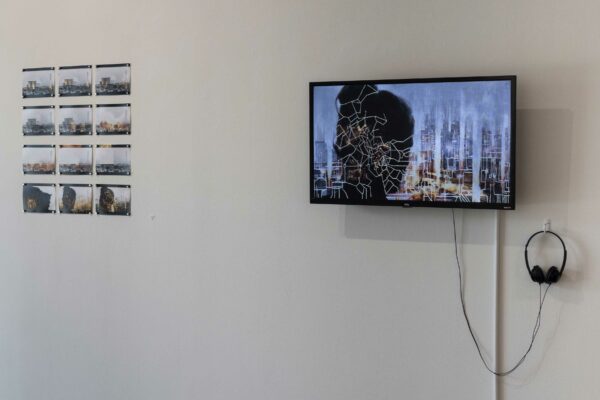

Moving onward, Moïa Jobin-Paré’s 4min15 au Révélateur/4min15 in the developer uses scratched photographs to narrate an exchange between a woman and a city. Jobin-Paré’s photographic manipulation produces a freneticism that seems to visualize the city’s electric currents. The figure is silhouetted against the urbanscape and Jobin-Paré’s mark-making begins to sprawl over her head like a map of the city’s routes, fragmenting her shadow. She uses her hands to weave a string or a copper wire, almost ritualistically, like she’s negotiating with the city to harvest its energy. Eventually, a power surge transfers the energy to her, sparking from buildings and infrastructure. 4min15 in the developer examines human relationships to place, and the effects that hyper-urbanization has on our energetic equilibrium. Jobin-Paré speculates that we can temper the frequencies of a dense urban center, instead of kneeling to its mercy, by finetuning our perception of it.

Moïa Jobin-Paré’s “4min15 au Révélateur/4min15 in the developer,” on view in “Dream States” at ICOSA. Photo: Leon Alesi.

Moïa Jobin-Paré’s “4min15 au Révélateur/4min15 in the developer,” on view in “Dream States” at ICOSA. Photo: Leon Alesi.

Whereas Jobin-Paré studies our relationship to place, Ala Nunu looks to human relationships. In Ahead, a cohabiting couple goes through their daily motions together – brushing their teeth, sitting at the kitchen table – except one does so without a head. The headless figure exhibits agoraphobic tendencies, frantically shutting doors and windows so as not to let the outdoors in. The headed figure sets off on a journey outdoors, leaving their headless counterpart at home alone. Nunu offsets the figures’ mental states by panning back and forth between the two during their time apart. While the headed figure trots along merrily, a jovial soundtrack accompanies them. Cell-like forms begin to seep inside while the headless figure curls up at home, sending them into a frenzied panic while the soundtrack quickens its pace to reflect their anxiety.

No longer a fortress, the headless figure bolts out of their home. Meanwhile, the headed figure returns from their journey with a souvenir for their partner: a head. But as their partner is nowhere to be found, the headed figure sits on their bed staring remorsefully at the body-less head. Despite its colorful and bouncy animation style, Ahead leaves me with a knot in my stomach. I’m reminded that even in partnership our internal turmoil isolates us from those who love us most and want to help us.

Next in the circuit, Shunsaku Hayashi’s Railment takes viewers on a quantum leap through a city’s metro system. Animated by graphite sketches and watercolor paintings, the opening scene is ordinary: a man stands alone on a train. However, what transpires from there is anything but ordinary. The man notices several train cars jostling, and soon after, the train’s interior goes black. When the light comes back on, the floor beneath his feet has changed states, liquifying. The man’s feet begin seeping down through the floor, and out of curiosity, he pushes his hand through. The perspective shifts below, showing his hand descending upon the metro system, grasping a passing train, and throwing it off the tracks like a puny toy. A mass of passengers exits the derailed train, filing like ants down a staircase that leads them to another train station where they board a new train accordingly.

On the crowded train, the phenomenon begins again as a man descends through the floor of the train car. The monotonous passengers will continue to get back on the train, no matter the disruption, just like the way the train abides by its scheduled routes. Railment feels like that existential moment when you snap out of your redundant cycle and hardly recognize yourself, your surroundings, or your purpose. The worst part of that moment is feeling like the outlier, the only person falling into the abyss while everyone else continues on.

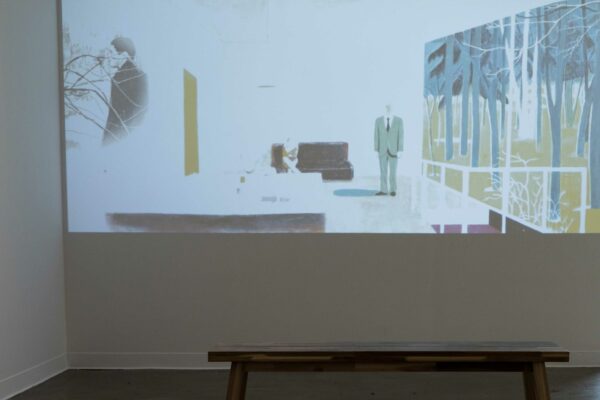

Railment conveys a snapshot of participating in the spectacle of society, but what would it look like to examine the spectacle as an observer? Sumito Sakakibara’s Iizuna Fair visualizes just that. Projected onto the wall, Iizuna Fair is a panoramic animation inspired by Sakakibara’s hometown festival. The animation feels like a one-shot scene because it essentially is; the film is made from one single painting, animated over a few seconds frame by frame. The panoramic shot continuously pans to the left, sprawling out an eventful day.

The first scene begins just moments after a car wreck. A figure stands on a small road with their hands on their head, facing a flipped car. The next frame is in a minimal interior where a man in a suit stands with alternating faces — one looks like Munch’s The Scream, and another is just a scribble of lines. Is this the man from the wreck? Did he have a head injury? Sakakibara moves on, providing no answers, exiting the interior and emerging into an outdoor scene. A bustling village gathers to enjoy a fair with ice skating, carnival rides, a large bonfire, and jousting, nestled lakeside at the base of a large hill. The viewing perspective is removed; we neither participate in the scene, nor are we acknowledged by the festival-goers. Eventually, we arrive back at the roadside wreck where the film ends and begins again. The continuous panning to the left implies a reversal, like Sakakibara is showing the events of the day prior to the wreck. Or, is the viewer’s perspective aligned with the protagonist in his new state, straddling realms between the living and the dead. Did he die? There is no concrete resolution, but Iizuna Fair elicits in me both nostalgia and grief.

Having finished the sequence of films, I feel as though I’ve trekked through a vast trail of emotions. I struggle to identify the feeling, because it’s not one I can even put a name to, but one that I feel deep in my gut. It took me back to when I’d watch raindrops roll across the window, in the backseat of my mom’s car, and I’d suddenly question the eyes that saw and the monologue that chattered on inside. Existential crisis? Perhaps, but for such moments, when reality feels anything but realistic, animation is capable of constructing a surreality to navigate the prompted uneasiness. These feelings are not visually accessible in the external world, but are internal experiences that vary in form, color, and sequence. In this way, Dream States uses animation to express the makers’ idiosyncrasies that individualize those feelings, while nodding to their universality.

On Saturday, May 13th, ICOSA will host a closing reception for Dream States with a film screening featuring five different films by directors Don Hertzfeldt, Elyse Kelly, Geoff Marslett, Anna Samo and Lisa LaBracio, and Sofie Cofer and Ala Nunu. The gallery is open 7- 10 PM, and the screening begins at 8:15 PM. Tickets for the screening are available on Eventbrite, and all proceeds will support continued ICOSA programming.