In 2005, when I was six, I thought George W. Bush was Superman. Seriously. So, I told him. Seriously!

When my first-grade class sent Flat Stanley letters to our choice recipients, I selected who I believed was the most powerful and righteous person in the world: the President of the United States. I specifically recall drawing him as a stick figure with a billowing red cape, alongside a detailed thank you for protecting us. From who? I wasn’t sure, but I knew there had been an attack on two skyscrapers in New York City and that the President was leading our country in a crusade against the attackers. He confirmed my idealization of him with a response that included a personalized letter describing my Flat Stanley’s trip to the White House — with photos. My parents still have that letter framed and on display in their house.

If I’d been old enough to understand the U.S. presence in Iraq at the behest of the President, I likely would not have described him as heroic. Or, perhaps I would have contemplated why, at such a young age, I believed the President was synonymous with Superman. Now I recognize how American ideals are disseminated throughout the culture by using the mass media as their vehicle, specifically using characters that children are drawn to, such as Superman. In The Superman Project (Part IV): Person Today, on view at Mercury Project in San Antonio until April 30, David Alcantar uses the ubiquitous Superman to analyze negotiations of power that inform American mythologies concerning military prowess, foreign and domestic policies, and religious morality.

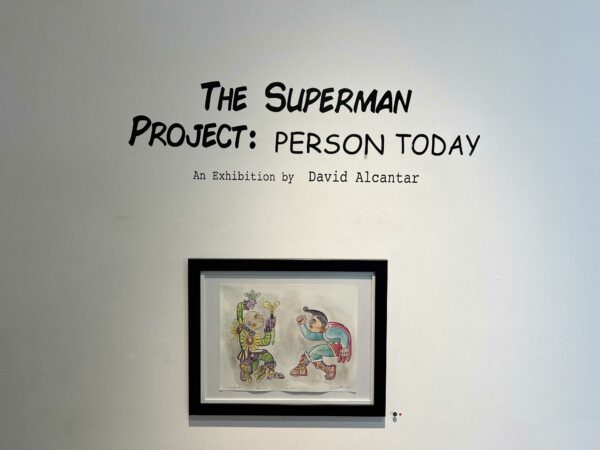

“The Superman Project: Person Today” on view at Mercury Project in San Antonio, TX. Photo: Caroline Frost.

The Superman Project (Part IV): Person Today catalogs two of Alcantar’s ongoing series: The Superman Project and The American. Each is conceptually rooted in negotiation, which Alcantar succinctly defines as “an exchange between two or more entities to arrange, settle, or pursue a particular interest by way of mutual agreement.” Alcantar explores negotiation as a behavior we exercise daily in previous projects, using tables and chairs as symbols for negotiating parties and branching arrows to represent the myriad possibilities that could arise from decisions made through negotiation.

The Superman Project began as a reaction to Donald Trump’s election as President in 2016, which Alcantar describes as a societal negotiation made among U.S. citizens in designating who would sit in the seat of American power. Building upon his past concepts of negotiation and now applying them to the American political environment, Alcantar needed a new symbol for negotiation that would also encapsulate the nation’s mythologies. Superman was the obvious choice.

“Even if we didn’t vote for [Trump], our actions, or inaction, participation, or lack thereof, during that time period and prior led to the outcome of Donald Trump becoming President of the United States,” Alcantar explains. “So, in thinking about how best to visualize this negotiation of power and heroization that we conducted as a country, it seemed obvious to use the iconography of Superman as the metaphor, because his physical power reflects U.S. military strength, his branded association to America reflects its capitalistic foreign policy, his immigrant story reflects domestic policy, and his morality and religious undertone serves as secular Christ, just to name a few associations.”

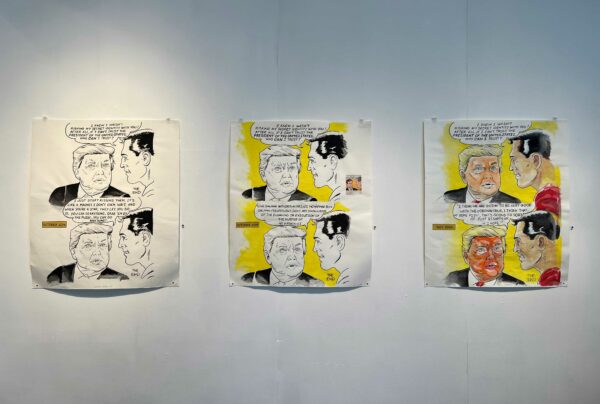

David Alcantar, “Identity Politics #1, #2, #3,” ink, tempera, collage on paper, 42 x 36 inches. Photo: Caroline Frost

The American, a performance piece, came to fruition in 2020 during early voting for the U.S. general election, and through the runoff elections that finally confirmed Joe Biden’s victory as President over the incumbent, Trump. The performance entails Alcantar running in Superman-branded clothing along high-visibility roads while carrying a three-by-five-foot flag boasting “VOTE” in large capitalized letters. Alcantar’s physicality gives credence to the character; he is tall and muscular, with wavy black hair. The objective is clear: Alcantar is leveraging a beloved American superhero’s iconography to encourage U.S. citizens to exercise their civic duty.

Displayed side-by-side in the exhibition, the two projects harmonize in revealing the conflicting qualities that arise when the country’s champion is compared to the country itself. Alcantar tracks the character’s trajectory in the country’s social consciousness alongside American historical events and cultural attitudes. In doing so, Alcantar uncovers the moments where Superman’s soapbox of “Truth, Justice, and the American Way” is directly contradicted by his actions and, by extension, the country’s social and political norms.

Featured works categorized by the subtitle Kill Your Idols demonstrate character flaws where Superman inadvertently represents the antithesis of what he claims to be. In Boys to Men of Tomorrow (Kill Your Idols #2), Alcantar features a comic strip from the original Superman, released in 1938 by writer Jerry Siegel and illustrator Joe Schuster. The narrative shows the heroic protagonist grabbing a woman from behind and bending her over his knee to administer spankings despite her protests. The woman exclaims “You can’t do this to me!,” to which Superman responds, “But I am!”

Above the comic, Alcantar displays a quote from Julie Baumgold, paraphrasing Donald Trump in an interview she conducted with him that was published in New York Magazine in 1992. It reads: “Trump is talking about women and says, ‘You have to treat ‘em like shit.’” The compositional relationship Alcantar establishes between the source material is clear: Superman and Donald Trump treat women as inferior to themselves. A more nuanced interpretation suggests that Alcantar is commenting on the societal negotiation we made as citizens in 2016, electing Trump as President, by reminding us of the documented misogyny Trump exhibited over 20 years prior to his election. Alcantar begs the question: do we excuse a fictional Superhero’s behavior over the man elected to run this country, or does the former’s justify the latter’s?

David Alcantar, “Truth, Justice, and the American Way, 1939 (Kill Your Idols #3a,b,c)” ink transfer, graphite on paper, 17 x 13 inches. Photo: Caroline Frost

In Truth, Justice, and The American Way, 1939 (Kill Your Idols #3c), Alcantar inserts a statistic from Human Rights Watch stating that “from 2002-2005, the peak years of the U.S. detention and torture program, at least 17 people died wholly or partly from abuse while in the custody of the CIA or U.S. military in Afghanistan, or the CIA and U.S. or British Forces in Iraq.” Below the excerpt is a comic strip showing Superman turning away from a man beaten to the ground behind a bush (seemingly by Superman’s hand), with what appears to be blood pooling around his head. “One less vulture!” Superman exclaims decisively. Again, Alcantar recontextualizes source material to draw a comparison between the fictionalized events in Superman and the very real war crimes committed under the guise of U.S. military strategy.

Kill Your Idols #2 and Kill Your Idols #3c establishes a direct parallel between Superman’s hypocritic heroism as the savior of our country and the beliefs and actions of the leaders of our country. Both comic strips were taken directly from the earliest depictions of Superman, in 1938 and 1939. One could attribute the misogynistic attitudes and brutal extra-judicial violence to a sign of the times when Superman was released — one we’d like to believe we’d hurdled over long ago. But Alcantar argues that’s not the case and provides the evidence to back it.

As much as Alcantar highlights Superman’s past characteristic failures, he also emphasizes how the character has evolved to reflect the country’s ongoing cultural concerns. For example, Alcantar recognizes Superman’s origin story as an immigrant story; Superman arrives in America as an infant from another planet and is raised in its heartland by two human parents, ultimately using his superhuman powers to protect the country he lives in. However, Superman is never entirely accepted as an American citizen despite his compelling efforts. Alcantar aligns Superman as an American immigrant while critiquing the U.S. immigration policy.

In Native Son (After John Byrne), Superman stands imposingly over the viewer, strong in his stance with every muscle in his body bulging and his cape swishing in the wind. Just behind him, a bright yellow rectangle recites section 212(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which outlines how and why an immigration applicant is deemed inadmissible to receive a visa or enter the country. Nodding to John Byrne’s authorship, Alcantar editorializes Superman’s reaction to the immigration laws; “It was Krypton that made me Superman, but it is Earth that makes me human!!,” Superman expresses as if lamenting his own experience as an immigrant in America.

Installation shot of “The Superman Project (Part IV): Person Today” featuring “Native Son (After John Byrne),” tempera, ink, graphite on paper, 53 x 46 inches. Photo: Caroline Frost

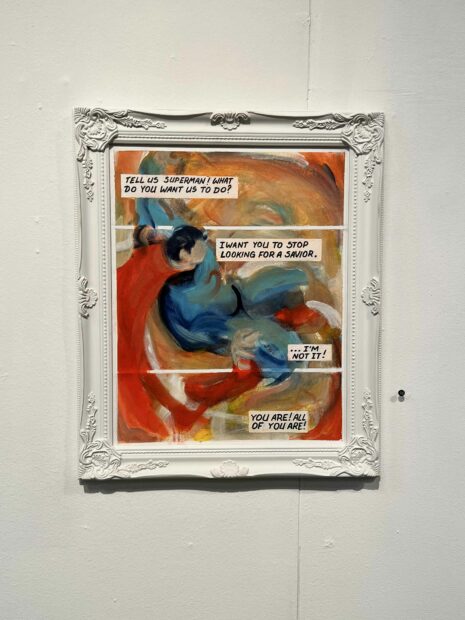

Alcantar also satirizes U.S. immigration issues through pieces like Alien, a watercolor mimicking a postcard. In Alien, Superman soars through the air, eclipsing “TEXAS,” which is sprawled across the sky, while Trump’s coveted border wall lines the horizon below him. Of course, the irony of America’s immigration controversy is that the country was built by immigrants. This is often veiled by the budding nation’s promise of religious freedom, which again, ironically, has repeatedly favored one religion among all others: Christianity. Thus, Superman is repeatedly perpetuated as a Christ figure, more so than an immigrant, satiating our need for a savior. Alcantar touches on this too. When We Believed, a mixed media sculpture composed of a red towel draped over a wooden coat stand, reminds me of ornamental monumentalizing of the resurrection of Christ. The red towel modeling as a cape reads like a religious relic. Phantom Zone (There is No Savior) features Superman directly addressing the public in response to their plea, “Tell us Superman! What do you want us to do?” While Alcantar’s facture sends him into an abysmal spiral, he responds, “I want you to stop looking for a savior…I’m not it! You are! All of you are!,” reminding them of the power of the masses.

David Alcantar, “When We Believed,” wood, Terry Cloth towel, clothespin, 62 x 22 x 8 inches. Photo: David Alcantar.

David Alcantar, “Phantom Zone (There is No Savior),” tempera and acrylic on canvas, 20 x 24 inches. Photo: David Alcantar

Alcantar reinforces this point by including Langston Hughes’ poem Let America Be America Again. Hughes, a Black poet and social activist, published the poem in 1936 (just two years before Superman was released, Alcantar notes in a handwritten annotation). Let America Be America Again chastises America for its failure to fulfill the promise of equality and freedom for all: “There’s never been equality for me, Nor freedom in this ‘homeland of the free.’” The poem concludes with a call to action, summoning the nation’s most oppressed — African Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, and the poor — to rise up in solidarity and rebuild America into a country that actually fulfills the ideals it was founded upon: “We, the people, must redeem the land, the mines, the plants, the rivers, the mountains and the endless plain, all, all the stretch of these great green states — And make America again!”

The rallying cry echoes Trump’s infamous campaign slogan. Alcantar, anticipating the viewer making that connection, finds an opportunity for parody. Below the framed poem is a blue baseball cap relaying the poem’s title, “Let America Be America Again,” obviously mocking the MAGA hat. Alcantar also renders the controversial image of Kanye West sporting the MAGA hat in two paintings flanking one portrait of Superman (in which Superman is noticeably tanned, almost orange). Next to the trio of portraits hangs a framed copy of Kanye’s statements from his meeting with Trump in the Oval Office in 2018. West is quoted telling Trump, “When I put this hat on, it made me feel like Superman. You made a Superman. That was — that’s my favorite superhero. And you made a Superman.” By hanging West’s statements and Hughes’ poem on opposite ends of the wall but with identical formatting, Alcantar situates “Let America Be America Again” and “Make America Great Again” as opposing ideologies that somehow converge into the same realm, with Superman as their commonality.

David Alcantar, “Don the Cape (components A, B, D, & E),” mixed media, variable dimensions. Photo: David Alcantar.

Superman functions in the same way that the horseshoe theory analogizes that the extreme left and the extreme right in politics actually closely resemble one another — everyone on either side of the political spectrum claims Superman as their country’s champion. In this sense, Superman is a mirror of our country, of us. He is a soundboard and a reflection of those authoring his continuing narrative and of the times they’re living through. He is mythmaking in real time. Where The Superman Project asks, “What do we gain by acknowledging the human limits of heroism and what do we concede by holding onto our desires for saviors?,” The American answers, “Agency.”

In The Superman Project (Part IV): Person Today, Alcantar reminds us that our individual negotiations have the momentum to affect change on a large scale, because microscopic actions have macroscopic outcomes. Recalling Hughes’ appeal, the best way to participate in forming the country we want to live in, to fill empty promises with manifestations, is by voting. Can we expect to see The American back on the streets leading up to the 2024 election? “Yes,” Alcantar confirms. “But unlike Superman, I am not ageless or invulnerable, so I can’t do it forever.”

David Alcantar pictured in front of “Truth, Justice, and the American Way, 1939, (Kill Your Idols #3a,b, & c)” on view at Mercury Project in San Antonio, TX.

The closing reception for The Superman Project (Part IV): Person Today is on Sunday, April 30, from 2-4:30 PM at Mercury Project, at 538 Roosevelt Avenue, San Antonio, TX 78210.