Years and years ago, Sallie Scheufler gave me an iced coffee for free. She was working in a cafe in Ahwatukee, which is a weird suburb of Phoenix where anything over five feet tall — be it building or rock — is some shade of pink. At that time we were both still kicking around Arizona after graduating from ASU’s photography program. I was working as an art handler in a more notorious suburb, and a free coffee was a boon. I’m still grateful to Sallie for that drink. Maybe I’m confabulating, but I believe we talked about applying to grad school as I lingered at the counter and got in customers’ way. We were friends — photo friends — we talked about stuff. Still applies.

Neither of us lives in Arizona anymore, and I think we’ve both started making art that is far more reflective of ourselves than the somewhat dour black and white landscapes we once stacked in front of each other’s faces. Sallie still lives in the Southwest. Albuquerque. I have to say I’m jealous. I was so happy to catch up with her on the occasion of her latest exhibition, which is called A Good Cry and is her first foray into the Texas art scene. It’s up now at Art League Houston, until April 22. There are performative videos, there are fiber works. There are also sculptures, including a series of hardened, sparkly Kleenex called Tear Crystals. Discrete cries, given shape and suspended in time. It’s wild.

Bucky Miller (BM): Did you actually turn your own tears into crystals?

Sallie Scheufler (SS): Mhm.

BM: Is it a secret process?

SS: Yeah it’s proprietary. Tears have a salt content. It takes a long time to make those pieces. Some of them failed. Like, some of them turn a chalky white after a while, which is not what I’m interested in. It’s important to me that the tissues feel precious, like gems, because they’re usually such a disposable object.

BM: It’s hard to think of tissues becoming archival. Like transporting those from Albuquerque to Houston seems like a really delicate procedure.

SS: The ones that are in the exhibit are five years old and delicate but solid. I also sold one to someone I know and it’s also still in great shape. It’s been encased in a shadowbox frame and stored in the dark. Speaking of storage, I just got a studio last year, and that’s been really great.

BM: Where’s your studio?

SS: It’s at this place called Harwood Art Center that’s really cool. It’s got a couple of galleries, they do a lot of educational programming. It’s housed in an old girls school north of Downtown Albuquerque, a really beautiful old building.

BM: How long have you been in Albuquerque now?

SS: Seven and a half years. I moved here to go to grad school at the University of New Mexico. I got my MFA, then ended up getting a job at Richard Levy Gallery. I’m staying around. They call it the Land of Enchantment, but the joke among the locals is the Land of Entrapment. It took me a while to settle into Albuquerque post-grad school, but I really loved it once I found another community and felt better situated. The academic community was nice when I was in school, but I needed something more permanent.

BM: I’ve known you since college. I still think about the first work I ever saw you do, which were these photographs of churches in strip malls.

SS: Wow, that was the first work you saw me do?

BM: Yeah. I met you in Mike Lundgren’s view camera class. I knew who you were before, I’d seen you in the hallways, but I hadn’t met you and I didn’t know your work. I know that you made a bunch of portraits of your family. But in my mind, still, every time I drive by a church in a strip mall I think of you and I think of that work. It seems so distant from what you’re doing now. The way that you’ve expanded, still maintain a photographic practice, but also are working in all these other ways, I think it’s really fascinating.

SS: It all still feels really relevant and really me. One of the pieces in A Good Cry is Birth Control Everyday/Everyday Birth Control. The visuals of that piece are really purposely nitty gritty. It’s a full year of videos of me taking my birth control pill on seven screens. Each screen is a day of the week; One screen is all the Mondays for the year, and so on. As they play in front of you, each video is a different length, so there’s an unlimited variety of ways to see them play. As I take the pill, I also show it to you as proof. It feels really ritualistic. But it’s got this choreography I made up for some kind of visual consistency. Most of the time I tried to record it in front of this kitchen wall that’s blank white. But sometimes I’d be traveling, so it gets messy.

Something about the recording in that video seems very related to the strip mall church photos. Even though those are very formal and beautiful, they look at the ways that churches have changed over time. At first I was really interested in the accumulated mass of churches, but I think by the end of the class I ended up pushing toward the more poetic.

Sallie Scheufler, “Birth Control Everyday Everyday Birth Control” (stills), 2018-2019, seven channel video and sound installation.

BM: That might have been the nature of the class.

SS: Yeah, I was gonna say. That’s class life. But also with those church images I’m thinking about organized religion, architecture, and urban sprawl. I keep that critical point of view through my practice. With the crying, I’m looking at my behavior of crying and analyzing it. With my family photos, it took me a long time to realize this, but I’m looking at the traumatic nature of family.

In my family I was told, “we need to be close, we need to love each other. Boundaries? What are those? Those aren’t important! It doesn’t matter how you were treated, we still need to love each other and be close.” I was asking questions about that closeness through beautiful images, but it was less direct.

But I think about those churches a lot too. I saw some really big megachurches in Texas.

BM: It’s the capital of the megachurch. Joel Osteen’s church is in Houston. He’s like the guy.

SS: I want to make work about the way that Christianity just doesn’t like women, it’s in the origin story. That was never a place for me, why would I ever want that?

BM: So you could say the through lines in all your work are these collisions of things that don’t feel like they should really collide, but do because of the way that capitalism in America works in the 21st century?

SS: Yeah, along with other systems of oppression like patriarchy, white supremacy, etc. With the birth control piece I’m thinking about how the pill, when it was first invented, was a form of freedom. Now for my generation it’s the opposite of that, in terms of not knowing what the pill does to your body. It is often detrimental to your health. That’s why it ended up in A Good Cry. Why is all this extra estrogen that I’m putting into my body affecting the way that I respond to things, how much I cry?

BM: Soon after I saw your churches I got to know you better and saw more of your work. At that point I would have thought of you as someone who photographed their family. You said you realized that was related to trauma?

SS: It’s not just trauma, but lived experience. I don’t want to put it into a trauma box. I’m really interested in how our lived experience makes us who we are and how we act in the world, how we have to learn and unlearn based on what we experienced growing up. My family work was me looking at that. I focused on my little sister for a long time. She’s ten years younger than me. I photographed her being born. I found the photographs a handful of years ago and realized I must have been the one to take them because my aunt was holding my mom’s hand and my sister was too grossed out. I remained really interested in photographing my little sister and her experiences growing up and coming of age. She’s a model now, and I’m sure that’s my fault.

Sallie Scheufler, “Sister Sister Sister or Sallie Stacie Sadie,” 2020, inkjet print, 20 x 30 inches, edition of 7.

I wanted to know how childhood experiences affect how we act, even as adults. So I have this much more intuitive body of photographs of my family and the house I grew up in, mostly the yard. Looking at the way things were taken care of or not, how that translates to what kind of personalities we have. Most of the people in my family were Virgos, but everything was untidy, so I’m still unpacking that.

I photographed the plant life at our house, because the plants were watered but never trimmed. They were overgrown, or just hanging on by a thread. They weren’t really taken care of, but they were given something.

BM: Frozen pizzas for the plants.

SS: Growing up was chaotic. I have a couple of unfinished pieces about sex talks my parents never gave me. I look at my relationship with sex and the way I learned or didn’t learn certain things. The shame there. I’m really interested in sex-positive education.

BM: You’ve got those banners [made from the hanging, metallic cardboard “happy birthday” signs].

SS: Which are encouraging for orgasms.

Then in 2020 I made a body of work called Family Resemblance that is about how much I look like my sisters and my mom. I look a lot like my mom and sometimes wish I looked like my sisters. It’s kind of a marriage of my photography and my performance work, which is something I wanted to do for a long time. It took a lot of time, distance, and processing to see how they were the same thing. Making that body of work showed me that.

BM: So where did the performance thing come from?

SS: When you and I met I was making those family portraits, but I had also just learned about what performance art was. I was hooked. I had this art history teacher who wasn’t great at teaching Art History 102. I always remember how in our last class of the semester she was like “we can cover the last chapter of the book, or I can tell you about my specialty,” which was performance art. So she gave us this lecture about performance art and it stuck with me so much. If she hadn’t done that I wouldn’t be where I am. And around the same time I made some new friends that were in the performance art area, so I started taking classes. But it took me a long time before I really felt comfortable making performance art and found my niche. I prefer making videos that are performance art. They rely on the timing and formatting of video. If they were live they would be totally different.

Sallie Scheufler, “Crying (onion, menthol, fan, fake)” (onion-still), 2018, 14 minutes and 10 seconds.

BM: Especially like eating a raw onion in front of a live crowd.

SS: I mean, that one might be an interesting live performance.

BM: It really would because everyone would start crying with you.

SS: It’s true. The fumes. They would also experience the fumes. So they would start crying. It would be a different piece because, okay, you’re consenting to be in this space and have a cry with me. It would be a communal cry, which would be interesting and healing in some way, but also painful because it’s an onion.

BM: Even that video is so damn uncomfortable to watch. I really love that piece. It’s called Crying, and it shows you making yourself cry on video in these ridiculous ways. I looked at the four-channel version of it that’s on your website, and it’s really fascinating because each channel has such a different tone to it. The onion one is horrifying and really intense. Like, visceral, in a gnarly kind of performance art way that has its whole own history full of weird freaks doing stuff to their bodies over in the corner. And then there’s the fake crying one which, I don’t mean this in a bad way, but is very annoying.

SS: Yeah. It’s funny, like it makes people laugh because they’re uncomfortable. They’re laughing, it’s annoying, and I had to do it because I was a big fake crier as a kid.

Sallie-Scheufler, “Crying (onion, menthol, fan, fake)” (fan-still), 2018, 14 minutes and 10 seconds.

BM: And then the one with the fan is a completely different form of comedy. That’s pure physical comedy. Just the image of your face with your eyes wide open staring into the fan. It’s an absurd image.

SS: Honestly, when I hold my eyes open it reminds me of A Clockwork Orange. That’s the only thing I can think of with that gesture, which is a horrific thing in that movie.

BM: There’s a bit of a horror to it, but…

SS: But it’s just the tiniest fan.

BM: It’s this really silly self-inflicted torture. And then the menthol one almost feels like a control. It’s the most subdued of the four. But the tears also feel the most real?

SS: So, actors use menthol to cry, which is how I decided to do that one. I was researching how actors do it. But the onion one was the first piece I made for the whole show. I was chopping onions to make dinner, and they were making me cry so much that I started wearing goggles. I’m very sensitive. Also my hands were getting stained with red onions, which is why I made the red onion hankies. It was really important to me that those be pink. There’s a slight homage to my granddaddy because everyone always talked about how he would eat onions like apples. But he would eat the sweet ones. He would never eat a red onion. It’s totally different.

So when I first shot the video I was like, “I have to eat the whole thing. It is so important for me to finish the onion.” Since it was the first piece in the show it was like a sketch of the idea. What I learned from doing that is that it wasn’t about endurance, it was about inducing. I only needed to eat it until I started crying. I actually had to shoot that three times because things kept going wrong. My body had this crazy reaction to the onion. It was more repulsed every time I did it.

BM: Oh no.

SS: I wasn’t trying to make a Marina Abramovic piece. I had to really consciously say that. Her work is so much about endurance and she’s also the first performance artist I learned about. Right after that class I was just telling you about, I was in New York for the first time and the universe was shining on me. She was performing The Artist Is Present and there was a whole retrospective at MoMA. Of course after I shot that video I showed it to my grad class and one of my friends was like, “you know Marina Abramovic did this?” And I was like, “no she didn’t!” She has a video piece where she’s eating an onion but hers, again, is about endurance. It’s way more hardcore. It’s got the skin still on it. For me the pieces are really different.

BM: Well, it’s context. You aren’t just eating the onion to eat it.

SS: I’m inducing tears.

BM: By any means necessary. It’s an experiment, your piece. It almost feels like “which one of these is the easiest way to cry?” In the show, it looks like it’s all shown on one monitor. Does it cycle through the four videos on the one screen?

SS: Yeah. This is my first time showing it like that. Before I did it projected, larger than life on a big wall. I had all four videos on different walls, and they would come on at different times. I really liked that and I was worried that I wouldn’t like it on a monitor, but I actually think it works well in this space. It’s fine if people don’t sit and watch all of them. If you get a taste of one or two and just learn about the others, I’m okay with that. It’s not so narrative that you have to sit through the whole thing.

Sallie Scheufler, “Futile, Handkerchiefs, Water-Soluble,” 2018, wash-n-gone fabric, tears, embroidery floss.

BM: Are those videos the only time that the physical act of crying appears in the show?

SS: Right, I don’t cry in the birth control videos and they are the only ones that have me in them.

BM: Is there any tear stain in the hankie pieces at all?

SS: The Futile Hankies, they don’t actually dry your tears or offer comfort. They cause more pain or embarrassment. One of the materials I used for those was this water soluble material that dissolves when you cry on it. In that one, you see the outlines of where I cried into the hankie, and the webbing does this really interesting thing that’s snot-like. There’s also a little snot in them.

BM: Those pieces present in a way that is super visually accessible, as these minimal fiber works. And then contextually they provide so much more. But what’s more accessible than crying? It’s such a common thing we all have experience with. There’s weird gender stuff there, guy’s aren’t supposed to cry; there’s a power thing. You’re pulling a lot of different emotions into crying. What made you decide it was the thing to go after?

SS: For me, it always feels like an inappropriate time to cry. I wish I didn’t cry at that moment. I wish I could control it. There were a couple professional situations where I cried and it was very inappropriate. That’s when I decided I needed to attack it and process it by making work about it. I want to understand crying more, and talk about it through my practice to whoever the audience may be.

I feel shame around crying. It’s like, “you’re inferior, weak, powerless. You should be tougher. Tell yourself not to.” Of course those professional instances where I cried were very stressful. One of them was when I was sick, on my period, and extremely stressed. My writing was being reviewed. I feel insecure about my ability to write because of a lot of lived experiences when I was told I wasn’t smart or capable enough to do it. So I cried and it was very embarrassing. The whole meeting turned into a conversation about whether crying was appropriate in those kinds of situations. Then I turned around and made work about it.

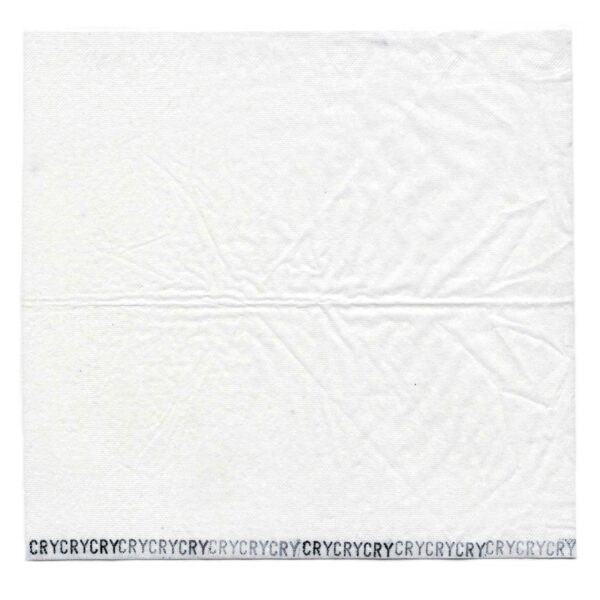

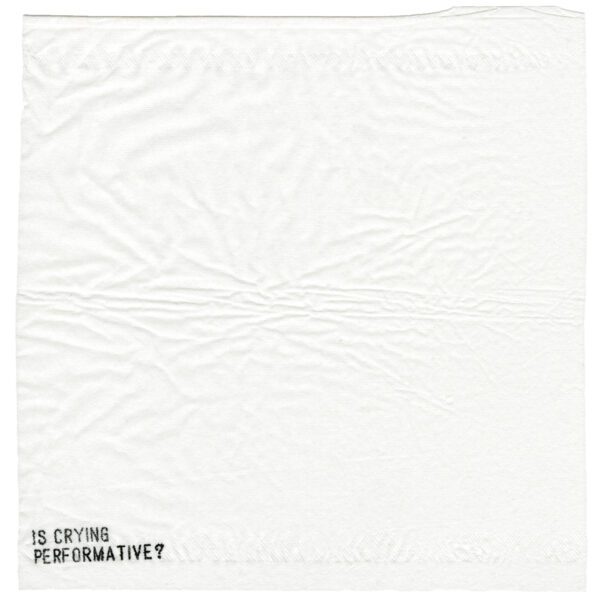

It’s important for me not to state what crying is, but to ask questions about it. One of the pieces in the show is an interactive tissue box where people can take a tissue with them. Each one has a question about crying on it for you to carry with you.

Sallie Scheufler, “Take a Tissue and Have a Good Cry (is crying performative),” 2018 -2023, stamped tissues.

BM: What are some of those questions?

SS: “How much of crying is learned?” “Is crying performative?” “Is crying an action or a reaction?” “Does crying equal weakness?” “Is crying always emotional?” And then one of them says, “cry cry cry cry cry,” it’s a performance score in my opinion. Another one says, “have a good cry.” The title of that piece is Take A Tissue And Have A Good Cry.

One big thread through my practice is the forms of nonverbal and verbal communication that we aren’t really aware of that create social power dynamics.

BM: The family, the church, that’s in all of it.

SS: It’s in everything. So I like to bring that to light. I’m asking, also, if crying is a form of communication. You think about that with babies, of course. They say with babies, if they cry you should pick them up because they’re trying to communicate something. So even the fake crying addresses that; how do we learn to cry as children? Were we told it was okay? Did you feel like you needed to be performative? Is it a way to gain power?

BM: It’s a lot. It’s a lot. I love crying.

SS: Huh?

BM: I love crying.

SS: Yeah! Cool.

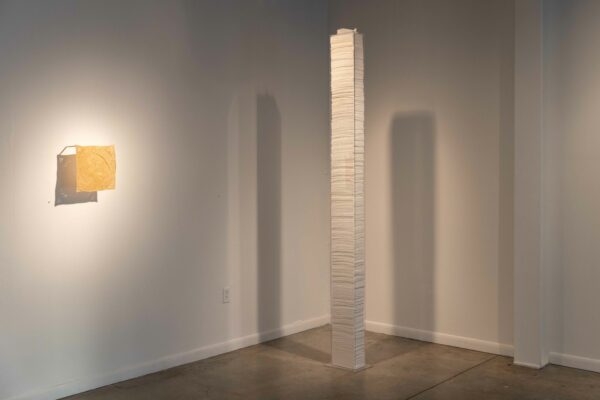

Sallie Scheufler, “Endless Tissue Box,” 2018, acrylic, approximately 7,000 tissues, 8 feet x 4 x 8 inches.

BM: I think it’s so powerful. I think it is communication. Even if it’s a way to communicate with something inside yourself. Even if it’s something really deep and in need of being reached that you can’t really get to through any sort of normal self reflection. Anyway, how tall is Endless Tissue Box?

SS: It’s eight feet tall. Industry standard largest sheet of plexiglass. Everything Is dictated by materials. There are about seven thousand tissues in it. That piece is kind of an engineering feat. When you put it on its side the tissues take up more space, so it can’t have a bottom permanently attached. You have to add enough tissues to fill it when you put it up, and lift it very carefully. It’s special.

BM: So you originally made this show for your MFA thesis. Does it feel good, years later, to bring it to Texas?

SS: I’m so against the idea that art gets old and you can’t show it anymore. I am really proud of this body of work and didn’t want it to have just shown in that one space. I was afraid of talking about it like my thesis show. I feel like most people make their grad school thesis and then think “okay, I don’t ever need to look at that again now I can start my real practice.” And I didn’t feel that way. I felt like this was my real practice and the first time I made a full body of work that felt fully like me. I love my family portraiture work, but this was me fully realizing my practice.

Everybody at Art League Houston was amazing to work with and so supportive. The experience of showing there has been great. There was an awesome turnout at the reception and the talk.

BM: And you ended up getting even more distance on the work than you planned, because the pandemic pushed your show years into the future?

SS: I graduated in 2018, which is when most of the work was first made. I applied to the show in 2019 and was awarded it in early 2020. The show was supposed to happen in 2021. All of the sudden that became five years after it was first made, versus two to three. I think that made me feel kind of funny about it. Now, having it in the gallery and hearing people’s reactions to it, I know it’s not just my grad school show. It was a struggle, but now it feels so good. Maybe I should show it somewhere else.

BM: Cart it around the country with you.

SS: The Endless Tissue Box fits exactly inside my Subaru Outback. All of the seats fold down, and the piece takes up the whole passenger side. My friend who rode with me to Texas had to sit behind me on the way there. We were worried we wouldn’t be able to hear each other, but it was normal.

BM: That must have looked so funny from the road.

SS: We had a cop pull us over and he asked, “are you moving?” And I was like, “no, it’s just my art.”

Sallie Scheufler: A Good Cry is on view at Art League Houston through April 22, 2023.