I first saw Abi Salami’s work in 2019 at a group exhibition entitled #UsToo-Phenomenal Women, curated by African American Museum of Dallas curator Jennifer Cowley. I recall thinking that the artist was competent, but not really taking any chances with her choice of imagery. While there was a definite feminist bend to the work, it didn’t suggest a willingness to tackle issues that might be difficult. I saw Salami’s work again in the online exhibition Girls Are Gods Too, curated by Jaelyn Wall, which explored Black feminism. I actually visited the site in order to see another artist’s work and stumbled upon Salami’s. Once again, I admired her technical ability and sense of design, but felt she was still playing it safe.

Fast forward to 2023 and Salami’s exhibition The Miseducation of Boys and Girls at Cris Worley Fine Arts. I was mesmerized by the new work. The timidity I saw in her earlier pieces was nonexistent. Instead of tiptoeing around difficult topics, like sexual commodification of the black body or hyper-misogynism, Salami was now confronting them head-on. I also saw a loosening of her painting technique, which indicated a greater comfort with her medium and confidence in her ability to manipulate it. This body of work is powerful, poignant, and definitely worth a thorough exploration by Salami. This conversation with her has me looking forward to her next exhibition, because I think she’s found her full-throated voice.

Vicki Meek (VM): You are relatively new to the visual arts world. Your educational path seems to have followed one I’ve noticed is often followed by first-generation African immigrant artists. The path starts with a degree in some technical, business, or medical field, but upon reaching an age where they can determine their own path, the artist emerges. When did your desire to make art in earnest take you away from your business education career goals?

Abi Salami (AS): I desperately wanted to go to art school. My father, a very practical Nigerian man, strongly objected to such frivolous plans. He said “Don’t major in someone else’s hobby, because they will beat you with passion.” He insisted that I major in something practical and general like accounting, and then from there I was “free” to do as I pleased. So I did what good Nigerian daughters do: I got a very practical accounting degree and became a very practical licensed CPA. I worked in Corporate America for almost a decade before life gave me the biggest push to force me to begin my journey as an artist.

I can honestly say that I was only working in Corporate America because I wanted to make enough money to create art on the side. Art has always been Plan A, I just didn’t know at the time that it was possible for me to make a living off of the crazy ideas in my mind. I saw my opportunity for the first time in late 2017. My company got bought out and I was being laid off, and I knew deep down that this was my chance to really go for it. Some people will say I was really brave, but probably I was more naïve than brave. But man, did I have passion. Since leaving corporate there hasn’t been one minute where I am not thinking about art. It drives my friends crazy! I have no qualms with spending my last dollar on my art because I believe in it so blindly and passionately. My route into the art world isn’t at all conventional, but it’s been a hell of a ride.

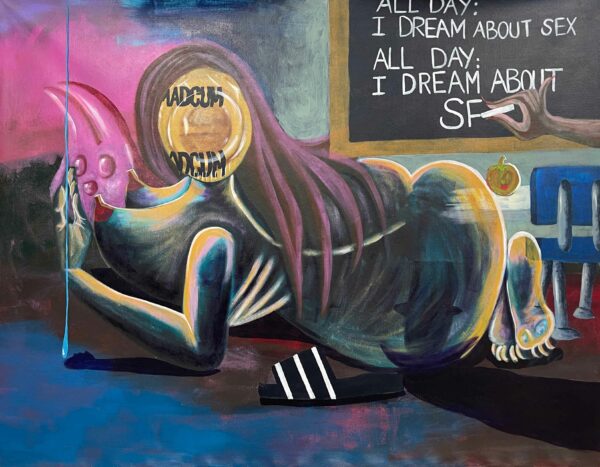

Abi Salami, “A.D.I.D.A.S. (All Day I Dream About Sex),” 2022 acrylic paint on unstretched canvas 54 x 42 inches unframed, 50 x 38 x 1 inches framed.

VM: Your work has always had a feminist focus, but it appears that in 2023 you began to take a deeper dive into issues that evoke more controversy than those you examined in 2021 and 2022. What inspired this shift in subject matter/issues?

AS: Everything changed when I moved to New York. I didn’t move to New York with the intention of being transformed, but it was a crash course in life lessons for the first three months. My artistic practice prior to moving to New York was very controlled. Everything was planned down to the T before I reached the canvas. In a world that seemed chaotic and frenzied, I knew I had control in my practice, which made me feel safe. New York robbed me of the safety within the first month of being here. You can come to New York as a control-freak, but she will very quickly humble you.

I learned very quickly that I had to let go of trying to control everything, because the only thing I could truly control was myself. That thought process spilled into my studio. First, I ditched the iPad that I had been using for years as my “safety blanket.” That was terrifying, because with an iPad, if you mess up, you just hit the back button until you’re back where you started, but I wanted to let go of that control. One day, while I was stuck on the first painting I completed in my new studio, I asked myself “what would you paint if you weren’t afraid?,” and I did. It felt amazing. And the more I painted, the bolder I seemed to become. That confidence, that boldness, that’s truly the only thing that has changed in my work. I am still talking about the Black female experience through my lenses, but I am doing it unabashedly.

I fully understand that the work might be too controversial for some, but that’s the point. I have found a lot of times when I am talking about my work, people seem to be more concerned about how pretty or beautiful I look, which is incredibly frustrating. Growing up, I was raised to be polite, take up little space, make sure to always smile. That’s the type of art I was creating back in 2021 and early 2022. Polite art. Deep within the symbolism was what I always wanted to say, but was too scared to. New York showed me how to find my voice.

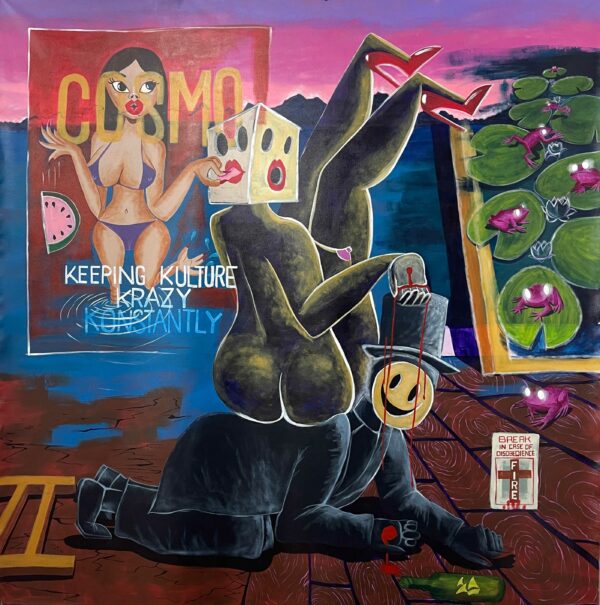

Abi Salami , “Keeping Kulture Krazy Konstantly,” 2022, acrylic paint on unstretched canvas, 84 x 84 inches, 80 x 80 x 1 inches framed.

VM: Are there any topics that you would describe as taboo when it comes to critical investigation of cultural mores? Would you find a way to represent these topics regardless of their taboo?

AS: I don’t think anything should be off limits when it comes to art. If society can come up with these taboos, we should also be able to speak to why they are taboo. Also, taboos change as society changes, and it is usually because of art. A notable example would be The Abortion Pastels by Paula Rego, which depicts brutally raw and vulnerable scenes of women obtaining illegal abortions and the effect it had on public opinion around criminalizing legal abortions in Portugal. For the first time, people were confronted with the horrors of illegal abortions and the plight of women, and they voted for change. This is what I believe art is supposed to do. If I am not scared while working on a piece, then I know I am not diving deep enough.

VM: Given that you have now begun to exhibit with commercial galleries, what have you learned as a Black woman artist about how the art world receives your work? Are there assumptions made about what work of yours is marketable versus what is not? If so, what are those assumptions?

AS: I have known — even before diving into the art world — that because of the vessel that I am in, I have to speak and act a certain way to be taken seriously. While working in the corporate world, I lost count of the number of times at the beginning of meetings where no one would shake my hands because they just assumed I was the secretary. I was the Director of Investor Relations, and most likely was the person they had been corresponding with prior to the meeting. Abi Salami is a gender-neutral sounding name to most people, so if I am doing something people perceive to be important and they don’t take the time to look me up, they just assume I am a man. So I am able to get away with a lot until people meet me.

Once that jig is up, I know I have to work twice as hard just to keep their attention. This double standard used to bother me, but not anymore. Because of it I am always pushing myself to go deeper. I want to be instantly recognizable, but never predictable. And I am sure my bravado might seem abrasive coming from a Black woman, but I have found that being true to myself tends to keep away people who are threatened by such confidence. I am not painting art for couches, and I am very fortunate that the people and galleries I work with really support and understand that.

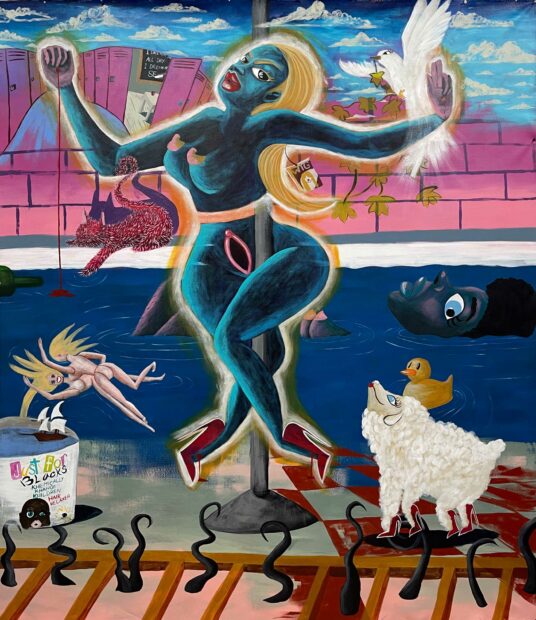

Abi Salami, “When We Come Running (The Lightest Heart),” 2022, acrylic paint on unstretched canvas, 81 x 84 inches.

VM: I’ve noticed that once your work shifted from a narrative that alluded to tough issues to work that embraced them without apology, you also seemed to utilize a more painterly approach to artmaking. Were you consciously making this shift, or did the subject matter lead you towards a different artmaking approach?

AS: Because I needed to control every aspect of my practice (probably due to insecurities about being a self-taught artist), my practice was lacking a key ingredient: Play. The move to NY and the revelation about not truly being in control released me from the desire to be perfect — to have perfect brush strokes, perfect lines, perfect compositions, etc. I started to paint “badly,” thinking I was so original, only to find out that Salvador Dali had done and said the exact same thing several decades ago. So yes, I start each painting with the intent to fail. It is truly liberating because if it is awful, then I can’t be upset, because that’s what I set out to do. However, most times it isn’t awful. Happy accidents happen all the time. I dance, sing out loud, stretch, and move my body as much as possible while creating, because I know some of that energy will find its way onto the canvas.

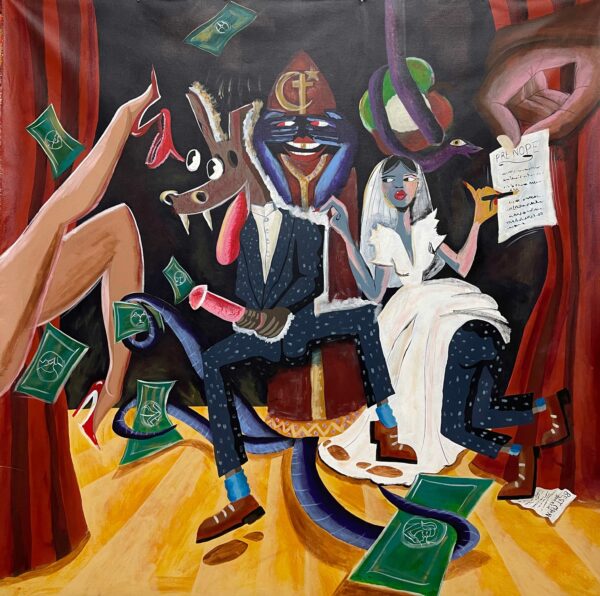

Abi Salami, “You Need A Savior (Who isn’t you and doesn’t look like you),” 2022, acrylic paint on unstretched canvas, 84 x 72 inches unframed, 80 x 59 x 1 inches framed.

1 comment

Abi’s work is amazing! This is the first I have ever seen it, and thank you for including so many images in this article. I am going to start showing her work in my Freshman Seminar and Intro to Visual Arts Class.