Muisca, Colombia, Votive Figure Seated on a Stool, 600–1500 AD, gold, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Alfred C. Glassell, Jr., against a backdrop of the páramo (tropical highaltitude ecosystem) in Colombia.

Photograph © Museum Associates/LACMA by Julia Burtenshaw

When entering the first room of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s Golden Worlds: The Portable Universe of Indigenous Colombia, one must adjust to the darkness. A miniature version of the Museo de Oro in Bogota, the room is a black box designed to highlight its gold pieces, glowing under low light. The metal pieces were etched into swirling patterns by their creators as a symbol of the cosmos and their endless undulations. “Art objects served to capture the universe at human scale,” the wall text explains, “allowing humans to care for and negotiate with the rich populations of beings that inhabit the spiritual universe of Indigenous people.”

Colombian religious and spiritual leaders of the Caribbean lowlands, Eastern Cordillera, and Middle Cauca Valley were said to drape gold pieces over their foreheads, noses, and chests as a way to transform themselves into superior entities. In the Nariño and Calima styles, artists used geometric shapes and outlining, as well as unique hammering techniques, to render complex motifs into the metal. The figures are otherworldly, a mix of human and animal. Many were worn in ritual activities and helped aid the wearer in transformation. In one piece from the region now known as Santa Marta, a delicately scored figure stands with water parted and cascading over their head. In both fists, a single serpent.

Calima, Colombia, Circular House Model, 200 BC– 800 AD, gold, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Alfred C. Glassell, Jr.

This first room is a glimmering slice of a much larger project, one that began in the spirit of exchange between Los Angeles curators and Indigenous Colombian communities in an attempt to address a long history of extraction and exploitation in Latin America. For the show, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in partnership with the Museo de Oro in Bogotá, LACMA curators traveled to Colombia over the course of four years to meet with the descendants of the cultures from which these artworks came. Writer James D. Balestrieri points out that as a result of these meetings and a greater understanding of the artworks’ spiritual significance, the exhibition’s curators realized that they could not display the materials as objects, but rather subjects, icons imbued with cosmic meaning. The exhibition catalog includes conversations with elders of the Arhuaco community in Santa Marta, northern Colombia. This particular essay, “To Dream a Dream Together,” is an exercise in hybrid storytelling, weaving in and out of conversation, creation myth, and present-day historical context.

(left to right) Nahuange, Colombia, Plaque Ornament with Human and Two Birds, 200–300 AD, gold, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Alfred C. Glassell, Jr.; Tairona, Colombia, Figurative Ocarina, 900–1600 AD, ceramic, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Muñoz Kramer Collection, gift of Jorge G. and Nelly de Muñoz and Camilla Chandler Frost; against a backdrop of the Caribbean coastline, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Photograph © Jota Arango

As a result of these exchanges, one of the elders proposed the creation of a Colombian museum and cultural center called Casa-Museo, or La casa de los ancestros que queremos ser (“the house of the ancestors we want to become”). It will be built as a replica of the universe, with rounded walls, woven palms, and four posts to signify the four cardinal directions, each one connecting the earth with the sun.

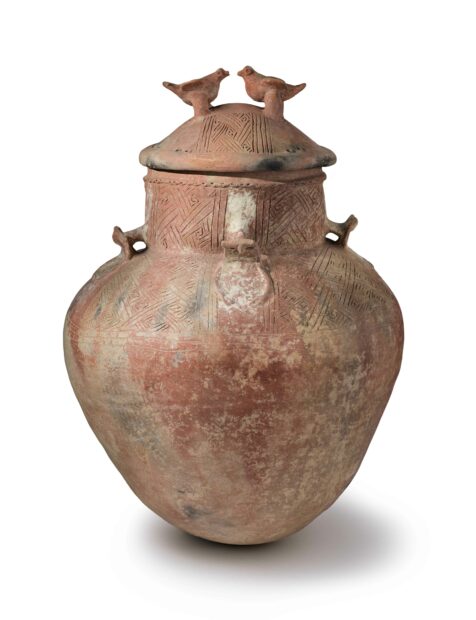

Colombia, Burial Urn with Two Birds on Lid, 900– 1600 AD, ceramic, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Muñoz Kramer Collection, gift of Camilla Chandler Frost and Stephen and Claudia Muñoz-Kramer. Photograph © Museum Associates/LACMA

Towards the back of the room there is a thick braid of gold, a thinly hammered line of figures tied together, bound by what could have been either hands or feet. These tumbaga works are meant to hold balance, a literal fusing of gold and copper. Golden Worlds brings up the politics of representation. Like the film Encanto, it forces us to ask what institutionally-backed visibility can mean to Colombians today? This winter, I first encountered the exhibition catalog not at the MFAH or LACMA, but on my mother’s coffee table, proudly displayed. Then I had the visceral memory of stepping into a similar darkened room in Colombia, my family by my side, peering into the glass and wondering what I was meant to learn about myself.

As a diasporic person, when traveling back to the Colombian Caribbean, I’ve been both home-comer and tourist. I’ve seen objects similar to those in Golden Worlds in shop windows in Cartagena, or sold at open air markets. I’ve gazed down at Santa Marta’s cityscape, gleaming, not dissimilarly, from the gold featured in the exhibition; on the horizon was a steaming, green hillside. I felt on a cellular level the split between land and industry, the divine and the overdeveloped. Santa Marta is a place of contradictions — eco-communes and organic cafés are nested alongside farmland. It’s a region constantly negotiating history, tourism, agency, and ownership, much like the curatorial process of Golden Worlds.

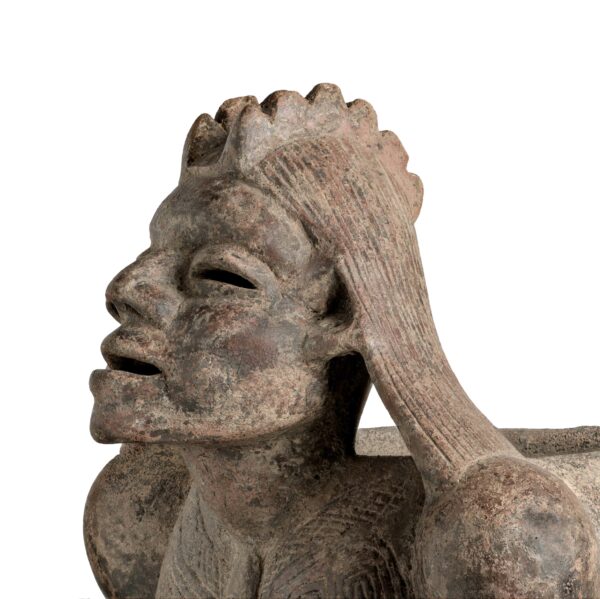

Calima, Colombia, Basket-Carrier (“Canastero”) with Incised Body Ornamentation (detail), 1000 BC–100 AD, ceramic, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Muñoz Kramer Collection, gift of Stephen and Claudia Muñoz-Kramer and Camilla Chandler Frost. Photograph © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Golden Worlds accentuates this chasm, this splinter in history between the ancestral, spiritual practices that these golden icons embody and their study by the Western world. In her essay, LACMA Deputy Director, Program Director, and Dr. Virginia Fields Curator of the Art of the Ancient Americas Diana Magaloni writes that the West’s relationship to these objects has been defined by categorization, the urge to classify work that was made for the purposes of the spiritual. “[W]e have used scientific techniques to establish their time periods,” she explains, “we have tried to interpret their encoded symbols and, when possible, their possible meanings and significance. Despite all this, we are always confronted with a powerful paradox: this Western pursuit of knowledge has precluded us from understanding the true meanings of these ancient items, and consequently their spiritual poignancy and humane resonance are obscured.”

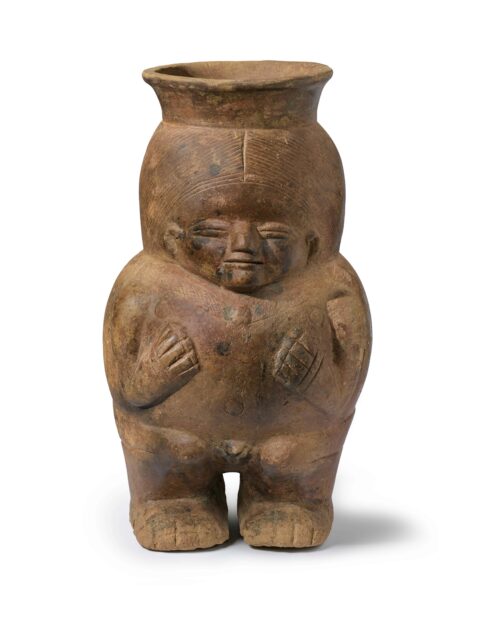

Calima, Colombia, Female Figure Container, 1500 BC–100 AD, ceramic, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Muñoz Kramer Collection, gift of Camilla Chandler Frost and Stephen and Claudia Muñoz-Kramer. Photograph © Museum Associates/LACMA

This admission invites the unknowable into the exhibition space. The exhibition collaborators have referred to Golden Worlds as a bridge between the indigenous communities of Colombia and Western cultural archivists. In thinking about the bloody history of colonialism and looting, both parties have deemed Indigenous Colombian participation in the project as an act of forgiveness, and forgiveness an act of consciousness. Only time will tell if, through projects like this, museum administrators can become the ancestors they hope to be. In this small room of the MFAH, the scientist meets the shaman — we feel the presence of the scientific and the spiritual in equal measure — and we know not what they will say to one another.

Golden Worlds is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through April 16, 2023.