Still from the film “Hard Core” by Walter De Maria, 1969, digital video transferred from original 16 mm, 28 minutes. © The Estate of Walter De Maria.

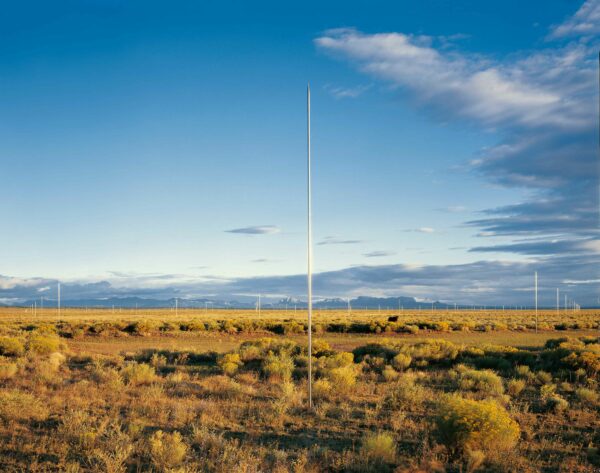

My original avenue of introduction to the work of artist Walter De Maria was an unusual one. Though I was vaguely aware of him as a sculptor and creator of the famous earthwork The Lightning Field, I hadn’t really seen anything until I was investigating the history of experimental TV and came across his short film, Hard Core. Practically unknown, it was commissioned for broadcast on San Francisco’s KQED TV in 1969. I couldn’t quite tell if it was an experimental masterpiece or a failed attempt at a Western movie sequence, but I was intrigued by its collision of formalist filmmaking, pop reference, and political hint. I liked the musicality of its spatial and temporal play — with slow, horizontal movements along desolate landscapes interrupted by static shots of cracked earth and figures with guns. I liked its use of layered ambient sounds and drum rhythms (for which the artist was also credited). I wondered why I hadn’t heard of De Maria’s film career, as Hard Core was similar and contemporaneous with the much-lauded films of Michael Snow. And I wondered if he’d done other music or sound works. Given these breadcrumbs, I began to think of his art in more cinematic and musical terms. Perhaps there is more than meets the eye in this guy’s stuff, I thought. And perhaps his work needs to be experienced directly to be fully appreciated.

Walter De Maria, “The Arch,” 1964, plywood, dimensions variable. The Menil Collection, Houston. © The Estate of Walter De Maria. Photo: Paul Hester

I’ve been able to see some of De Maria’s work in the years since then. The Menil Collection’s great 2011 Trilogies exhibition and their later inclusion of his small, strangely alluring metal sculpture High Energy Bar in a group show furthered my interest in seeing and learning more. But it was not until the arrival of the artist’s first-ever museum survey and the coinciding release of the first comprehensive book covering his career that I was able to really delve into the mystery of De Maria’s conjurings. Curated by the Menil Collection’s Senior Curator Michelle White and former Chief Conservator Brad Epley, the exhibition Walter De Maria: Boxes for Meaningless Work (currently on view at the Menil Collection through April 23) includes sculptural constructions, paintings, drawings, photographs, films, and sound works spanning his career — including some that are presented publicly for the first time in many decades. My visits to the exhibition have opened my appreciation of De Maria’s work, and my first forays into the essays, images, and comprehensive chronology in the new book, Walter De Maria: The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling (published by Gagosian, available at the Menil Bookstore and elsewhere) have illuminated his varied influences and efforts.

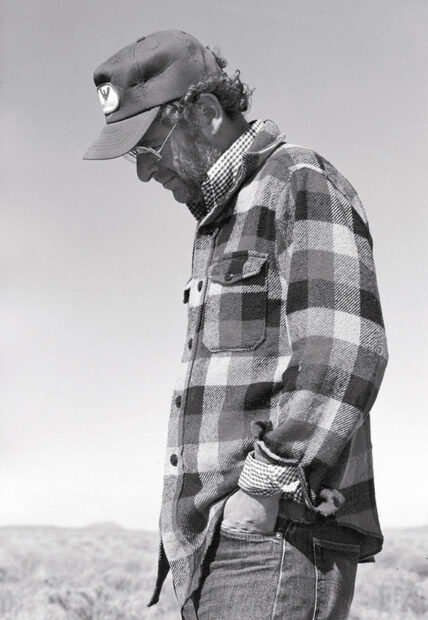

While he’s most associated with 1960s New York, Walter De Maria spent his formative years in 1950s San Francisco and Berkely. He was indeed a musician from an early age, playing drums and percussion with school bands and then professional symphonies and jazz ensembles. Between music gigs and museum trips, he studied political science and art history at the University of California at Berkeley. As his own visual art practice shifted from improvised abstract painting to static sculptural forms, his good friend La Monte Young ignited new musical impulses, introducing him to the ideas of John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen. He and Young collaborated on a series of “high friction sound” performances that could be considered the first Happenings on the West Coast. Through the influence of Anna Halprin and others, he became interested in indeterminacy, instruction-oriented processes, and theories of movement. Following Young, De Maria moved to the East Coast in the fall of 1960. After casting a very wide creative net in California, the 25-year-old artist arrived in New York City’s art scene at a seemingly perfect time, at the beginning of a transformative decade.

In reaction against then-predominant Expressionism, De Maria had designed a number of small, wooden box sculptures before arriving in New York. He said in a later interview that the simple geometric forms “contained all the right information about the universe, and about oneself, and about the time.” Which is to say, nothing and everything. During his first couple of years in New York, he constructed dozens of these structures and also started a series of very simple, light-touch “invisible drawings” on white paper. While his visual work suggested a restrained concentration of energy and pointed to a developing Minimalist movement, De Maria also continued a wild variety of music and performance endeavors. He further collaborated with La Monte Young and musicians associated with Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music, participated in a series of performance events at George Maciunus’s AG Gallery, jammed with free jazz trumpeter Don Cherry, played with the short-lived art noise band The Druds, and was a member of the fluke proto-punk rock band The Primitives, which later morphed into the Velvet Underground. He also dabbled in media, creating a few of his own music and sound recordings and, later, a couple of film projects — the most fully realized being the aforementioned Hard Core, which utilized those previous audio recordings.

Though generally considered peripheral endeavors, his varied temporal work–collaborations as a musician (specifically, a drummer) and experiments as a media maker–unlock some interesting things about his focused work as a visual artist. They point to a spirit of experimentation and cross-pollination, to his interest in the visceral experience of free and immersive art interaction outside the confines of traditional gallery-going. They highlight fundamental ideas of rhythm in his work, and the spatial evocations of time in his forms. And they inform his trajectory into larger scale, immersive earthworks. One might think of these tangents as his core experimentation in the realm of imaginative possibility — the ephemeral, invisible stuff contained within his controlled, sculptural arrangements. All of this was overlapping and simultaneous in his career, and I’m glad to see these activities and connective elements foregrounded in the book and reflected in the exhibition. It’s a slight but necessary corrective to previously oversimplified summaries of De Maria as simply a “minimalist sculptor.” He was a wide-swath, multidisciplinary artist — first, and throughout.

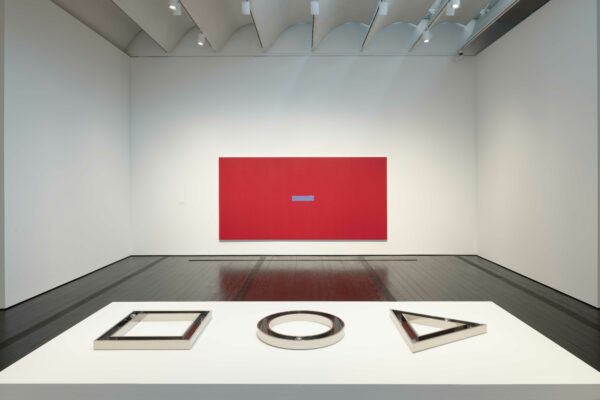

Installation view of “Walter De Maria: Boxes for Meaningless Work,” at the Menil Collection, Houston. Foreground: Walter De Maria, “Channel Series: Triangle, Circle, Square,” 1972. On wall: Walter De Maria, “The Statement Series: Red Painting / NO WAR NO,” 2011. © The Estate of Walter De Maria. Photo: Paul Hester

Walter De Maria: Boxes for Meaningless Work is the first exhibition to create a playground of combinations and cross-activations between a large number and a wide range of his pieces. Wood and stainless-steel sculptures, small drawings, large paintings, things related to the development of his land art projects, and media pieces all bounce off of each other very nicely. The film Hard Core is presented here in a recent digital restoration alongside his Ocean Bed — an interactive installation which invites visitors to lay down and listen to two oceans simultaneously. Presumptions about his art world categorization fly out the window as one experiences the confluence of boldness and subtlety, seriousness and silliness, elegant precision and poetic funk, familiarity and other-worldliness. Though it’s in the service of contemplation, there is an unexpected humor and absurdity at play in the show, as well as an underlying sense of rebelliousness. These slight frictions inexplicably send the viewer’s experience into echoes beyond the work itself.

The exhibition draws its title from one of the earliest included works, and one of the first that one sees upon entering. Both disarming and enlivening, the simple piece Boxes for Meaningless Work instructs the viewer to transfer the contents of one box to the other and back again, repeatedly. Most importantly, it suggests to “Be aware that what you are doing is meaningless.” This piece and its use as the show’s title is funny, though De Maria insists in a 1960 essay that considering the importance of accomplish-less activity is not a joke. He apparently featured a version of Boxes for Meaningless Work during one of the early performances he and La Monte Young did in San Francisco, performing its meaningless activity himself. The static piece, as shown here, works just as well in one’s own imagination, as do other instructional works that can’t be physically activated in the museum. It essentially acts as an invisible performance, and in fact, its prompted thought experiment suggests a good approach of imaginative interaction as one proceeds through the rest of the exhibition.

The presences and absences in the show, the various scale relationships in the work — actual or implied, the nudges of titles and bits of text — specific or general… These are all composed suggestions to evoke experience, but not at all to define conclusion. Visitors are gently provoked into the intersections of meaning and meaninglessness, visible and invisible, real and imagined. In a sense, all of De Maria’s works are temporal, in that they activate over the duration of time one spends with them. And as they’re complete only in one’s own personal engagement with them, each work is unfinished. De Maria’s diverse projects and resistance to the limits of conventional art and its presentation were not simply born of creative restlessness. Rather, this was part of a continual, purposeful effort to entertain incongruence and to design the simplest vessels for complexity in service of unseen possibilities. Or, in his own words, to “allow for the greatest possibility for the works to be seen freely.”

Something that Walter De Maria said in a 1972 interview, which is referenced by Christine Mehring’s essay in the new book, strikes me as key to the artist’s approach: “Every good work should have at least ten meanings.” With this, he reveals that one intended art experience is both not enough and too much. And that even three or five possible paths of navigation are not sufficient for successful art. At least ten. This is the credo of a conjuror who values the art experience over the art itself, and as carefully refined as his works are, values the open imaginary and simultaneous multiplicity over the artist’s control. Later in the same interview, De Maria relates, “I looked for the balance in my life in a very simple-minded way, a balance between thought and action, a balance between emotion and thought… between the city and the west, you know, between everything.” Perhaps all of his impulses and influences, and perhaps all of ours, are not held in the forms so much as released in the mirages of “meaningless” movements between them.

Walter De Maria, “The Lightning Field,” 1977, four hundred stainless steel poles, West central New Mexico. Commissioned and maintained by Dia Art Foundation, New York. Photo: John Cliett. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Walter De Maria: Boxes for Meaningless Work is on view at the Menil Collection through April 23. Walter De Maria: The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling is published by Gagosian and features contributions from Elizabeth Childress, Michael Childress, Dagny Corcoran, Donna De Salvo, Larry Gagosian, Michael Govan, Christine Mehring, and Lars Nittve.