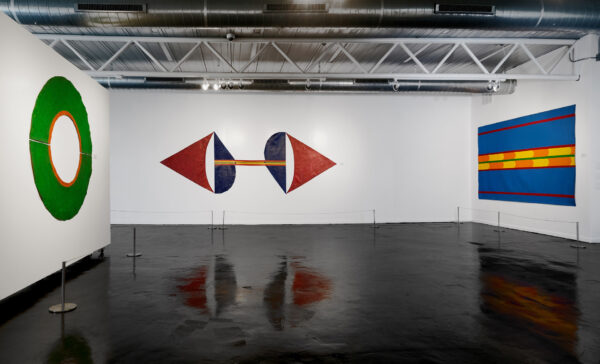

Ellsworth Ausby, installation view of “Odyssey,” on view at the Houston Museum of African American Culture. Photo courtesy of HMAAC.

According to Roman myth, painting emerged from a literal shadow. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, tells us that Eudora, a female citizen of the city of Corinth, traced the outline of her lover’s shadow while he was sleeping. There are many depictions of the momentous event, and it is hard to overstate the importance of this founding myth for Western art history. The implications of the Corinthian maid’s invention are the primacy of drawing over color, the centrality of the human figure, and the insistence on the static object, i.e. a sleeping lover or a reclining nude. But what if the origin myth was different? Ellsworth Ausby’s retrospective at the HMAAC dares us to imagine the alternative.

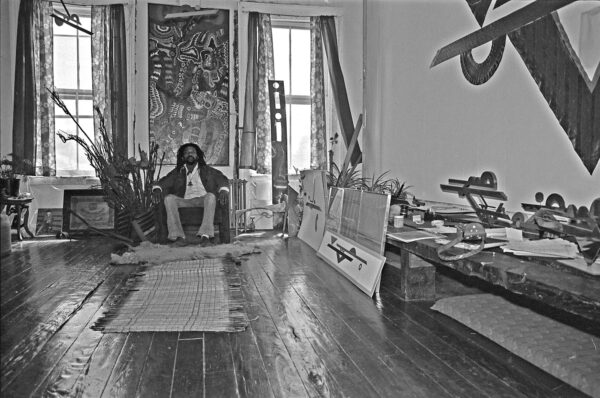

A photo of Ellsworth Ausby. Photo by Blaise Tobia 1978, for the CCF CETA Artists Project. © Blaise Tobia 2023.

Ausby, who died in 2011, had his revelation in the late 1960s. While working as a waiter at Slug’s Saloon, New York’s legendary jazz club, he witnessed a performance by Sun Ra. The very name of the legendary jazz musician and thinker implies a different source of creativity. As Sun Ra put it in an announcement for his seminal record, Super-sonic Jazz, “there is nothing new under the sun, but the music of the sun is new because the sun is the pace-setter of tomorrow.” Pioneering an avant-garde form of Black consciousness that would later be termed ‘Afro-Futurism’ in a 1993 article by culture critic Mark Dery, Sun Ra synthesized Methodist church sermons, free music, and an interest in Egypt and outer space. Ausby took this mixture to heart. He went to Egypt in the 1970s, then to Lagos in 1977, for the “Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture,” where he met and befriended his African peers. In his work, Ausby is successfully digging for the Black gold of the sun, to paraphrase the classic Rotary Connection song from that era.

Ellsworth Ausby, installation view of “Odyssey,” on view at the Houston Museum of African American Culture. Photo courtesy of HMAAC.

Principles that Ausby shared with other artists of the era include the romantic notion of a sublime object, and of a painting being a source of light in itself. By this time, several artists outside of the museum mainstream took giant steps towards a new kind of non-figurative art. This one was much more fluid than the Minimalist approach, with its reliance on a sturdy core of architecture and geometry. Joe Overstreet and Sam Gilliam experimented with unstretched canvases of complex shapes. Brazilian maverick Helio Oiticica wandered the New York subway in his ‘parangoles,’ wearable abstractions of outlandish color. In London, British-Pakistani minimalist Rasheed Araeen conceived of Disco Sailing (1970), a performance that turned humans into free-floating yachts.

Ausby took on the challenge and did away with framing, putting his paintings straight on the wall to create, as the show’s curator Christopher Blay notes, something of a tapestry, a sensation of three-dimensional space. On a canvas, it works best when the movement of the shapes is horizontal. In a simple structure like Hey, That’s Nice, Uh! (1970), the shapes look like a row of books on a conveyor belt and pulsate from left to right, as if extending indefinitely into infinity. Grooving (1970) introduces a more complex rhythm of triangular lines, serving as accents to the steady flow of luminescent form.

Ellsworth Ausby, installation view of “Odyssey,” on view at the Houston Museum of African American Culture. Photo courtesy of HMAAC.

Arguably, the exhibition’s centerpiece — and the most sun-like painting on show — is Untitled (1974) in the Bert Long Jr. gallery. Blay calls it “an upside down version of the Rothko chapel,” and while Ausby has probably not pursued the connection, the painting is exactly that, centering the light, not the gloom and doom. Ausby’s works are generally optimistic, it must be said, and easily earn another of Blay’s elegant formulations: “benevolent abstraction.”

While a lot of what is now called Afro-Futurist in art bears no relation to the original historic movements in Europe, Ausby’s work shares important similarities with Russian and Italian Futurisms, in the same way Sun Ra’s music is partially informed by atonalities of Dmitry Shostakovich. First of all, like him, they prioritized movement as the main subject of their art. Further, in 1910, avant-garde pioneers Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov invented ‘rayonism’, a type of abstraction that foregrounded sun rays as the formative principle of the pictorial space. Italians were not far behind, getting more abstract as the World War crept in. Ausby’s shapes remind one of Fortunato Depero, one of the most playful Futurists, who spent several years in New York designing covers for magazines and stage sets. Ausby might have seen examples of his style, though Depero’s visibility was limited.

Ellsworth Ausby, installation view of “Odyssey,” on view at the Houston Museum of African American Culture. Photo courtesy of HMAAC.

Interesting as this comparison may be, it is incidental in relation to Ausby’s Afro-centric universe, with a history that spans millennia. Ausby’s interest in African art and design in ancient times and the present guided him towards a total vision of emancipated color. The last twenty or so years of rewriting art history to uncover biases have taught us that hostility to color can betray much more sinister exclusions of race, gender, and class. Now, museums and galleries are much more open to all kinds of heterogeneity, including Gnosticism and theosophy beloved by Sun Ra, and, of course, tone relationships that go beyond both the complementary palettes of Minimal artists and the Day-Glo color schemes of Pop.

Ausby’s paintings would be a perfect fit for the Met’s exhibition Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color. In that show, the nation’s leading institution restored polychromy to copies of white marbles of Ancient Greece. Ausby’s art takes after Egyptian color schemes that might have been influencing the Greeks. A wider, political meaning of his art in establishing a dignified Black culture on an equal footing with the Western European canon, however, is still to be realized.

Ellsworth Ausby: Odyssey is on view through April 7 at the Houston Museum of African American Culture.