When viewing the current show at Redbud Gallery, a visitor might be struck by a number of distinct and different bodies of work: flags, digital images, lab specimens, artifacts, or oil paintings on paper. But if the visitor steps back and looks at the work through a wide-angle lens, they’ll find an exhibition split into two: work inspired by the experimental selective breeding of pigeons by Charles Darwin (author of the Origin of Species), and installations with depictions of various aquatic species from the Gulf of Mexico. Though they may seem superficially unrelated, the works cross a hundred-year timeline of human manipulation and negligence toward nature and the environment.

This is an art show revealing two types of human interference in the natural world. One is intentional — Darwin’s 19th century experiment with biodiversity. The other interference is by way of criminal ineptitude from the 2010 British Petroleum Deepwater Horizon disaster (the largest oil spill in history).

Historically scientists identify, document, and categorize the history of species on the planet while working in obscurity inside the walls of museums and institutions. As art gallery visitors to Redbud, we see an artist’s version of a methodology doing the same, but with a focus on human intervention with nature.

The title of the exhibition, Sculpting Endless Forms, refers to the intentional or unintentional methods of genetic modification by humans. Artist Brandon Ballengée presents his version of a taxonomy (the science of categorization, ordering, and renaming) of organisms in the process of extinction. The work could be seen either as a visualization of disappearing aquatic species or as an impending warning of future events. While the exhibition clearly directs our attention to the major responsible party, it suggests some self-reflection from the onlooker. Are we willing to assume stewardship for these missing animals, or do we continue to allow our modern habits to passively contribute to species eradication?

Brandon Ballengée, “La Mer des Enfants Perdus (The Sea of Lost Children),” installation detail, 2017/21. Photo: Henry G. Sanchez.

Rather than overwhelming the viewer with emotional output, Ballengée skillfully presents work that arouses a sense of wonder through multi-media and laboratory experimentation. Specific titles allude to classical or modern day mythologies. You’ll see black banners hung from the ceiling depicting X-rays of missing Gulf species. They are pirate flags, an innocuous reference to Jean Lafitte, still a folk hero in parts of coastal Louisiana, where the artist now lives and works. (Ballengée’s goal is to one day have small fishing craft hoist the flags as a lookout-signs when they collect their catches.)

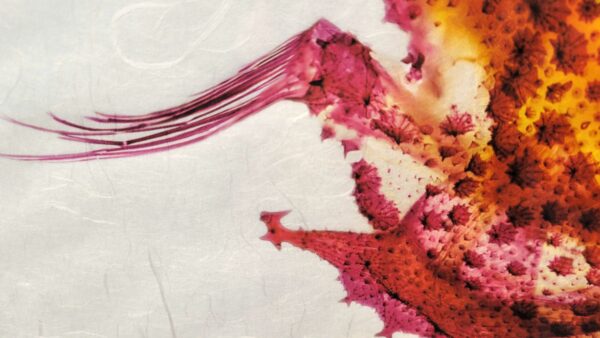

Aligning one corner wall are tiny vessels containing grass shrimp specimens. Each went through a preservation process involving the clearing and staining of animal tissue, rendering them transparent while coloring their cartilage. The results show mutations and physical deformations due to high exposures from the Deepwater oil spill. On the wall adjacent to them are a set of beautiful digital prints of larger marine organisms, also subjected to the clearing and staining process. These Gulf fishes, however, are in decline. Some of the most curious works are what seem at first to be mud-stained watercolors. In fact, the medium is recovered crude oil collected on Louisiana shores (again, from the Deepwater Horizon disaster). These paintings are of the newly extinct Gulf species.

Brandon Ballengée, “Crude Oil Paintings – MIA Spreadfin Skate” (detail), 2020. Photo: Henry G. Sanchez

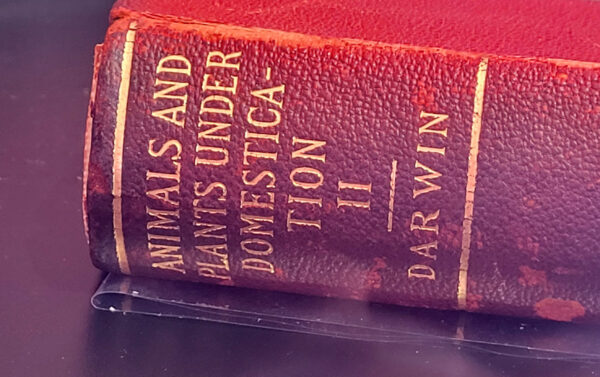

In the adjoining room is a body of work Ballengée completed during an artist residency at the Natural History Museum of London in 2009, consisting of photographs of the pigeon specimens from Darwin’s breeding experiments. These genetically modified varieties are superimposed on a material, making them seem as if they’re floating on a skyscape painting from the Romantic period. On display is a vitrine with the first two volumes of Darwin’s The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. Above that hangs Ballengée’s photo of a pigeon skull, marked by the hand of the great naturalist himself. This room evokes an antiquated 19th century sensibility of art intersecting with science, like bio-art from Jules Verne.

There are extensive essays about Ballengée’s work by many esteemed writers. For the sake of this article, I attempt to articulate how the artist’s work fits within the definition of bioart today.

So, what is bioart? Four years ago I wrote an article about bioartists in Houston, describing the various facets of what is considered bioart. (1)

Bioart is a highly disputed term because there are so many sub-categories involving multiple practices. The pioneering bio-artist and theorist Suzanne Anker outlines several types of aesthetic genres that emerge from this interdisciplinary field. One is by way of mimesis, or the depiction and appropriation of images that come from the scientific sphere. They reference scientific images such as MRI body and head scans, gene sequencing, sonograms, photos of laboratories, etc. Those images take the form of traditional mediums of painting, photography, sculpture, and other aesthetic presentations.

Second is the introduction and usage of science technologies and tools, such as laboratory equipment, microscopes, 3D modeling software, digital media, high-tech robotics, and A-I theoretical models to make individual artworks and art installations. A third is the use of living bio-matter as the art medium, or what is called “wet laboratory practices.” This artwork attempts bioengineering, incorporating live specimens, bacterial samples in petri dishes, or cloning of plant and animal cells, to name a few techniques. Finally, a fourth genre employs the usage of new narratives to explore ethical and philosophical implications. In what Anker calls “magical thinking,” experiments and theories about unknown areas of science and biology, which challenge traditional paradigms, can invite new bio-speculations and evoke worlds of wonder and curiosity. (2), (3).

Brandon Ballengée, “A Habit of Deciding Influence – DP 9.2,” (detail), 2003/09. Photo: Henry G. Sanchez

Bioart genres now also include social practice and social engagement to address the socio-political and environmental imperatives we face today. For example, a bioart social practice can foster individual and community agency over environmental issues; it can summon attention to ecologically strained sites with placemaking; it engages young citizen scientists to explore the practice of microscopy in their local ecosystem; or it may inspire political action to the problems we see in nature. (4).

Tying all these together is an underlying proposition that many ethical practices in science, as well as their intersections with art, can and should be questioned. Inquiry into the frontiers of science and biology with a sensitivity towards the economic, political, societal, and environmental implications and ramifications becomes a central theme in the most effective bioart works. (5).

My contribution to the new bioart literature details examples of how ethnic and personal history, cultural practices, social engagement, as well as intimate and spiritual mediations intersect with the science-art aesthetic. It gives additional depth to the “cultural imaginary” in bio-art today. (6), (7), (8).

Brandon Ballengée, “A Habit of Deciding Influence,” (installation detail), 2003/09. Photo: Henry G. Sanchez

Ballengée’s art also includes the practice of social interactions. During his many art residencies he has commonly led “experimental field trips” with students and the public. He refers to these as “eco-actions” meant to foster citizen scientists with nature workshops and explorations. His most recent project is a nature reserve that he and his family (with his wife Aurore and children Lily and Victor) have founded, called Atelier de Nature. It is an outdoor educational center inviting his community to explore its 25 acres with science, art, and conservation methods, while promoting stewardship and “positive eco-actions.” This is new territory for the Ballengée family, in that they are venturing into long-term placemaking.

If you wish to experience one of Dr. Brandon Ballengée eco-actions, meet and join him for an art-science and specimen drawing workshop on Gulf fish species diversity. It happens Saturday, February 25 from 3-5 pm at Redbud Gallery.

Sculpting Endless Forms exhibits a range of bioart genres. These variations reveal the implications of scientific intervention and our reliance on fossil fuels. The show is an artist’s version of natural history and a record of our complex relationship with missing species, which spans over one hundred years. Ballengée’s art presents a taxonomy for our time.

Brandon Ballengée, “La Mer des Enfants Perdus (The Sea of Lost Children),” detail, 2017/21. Photo: Henry G. Sanchez

It’s a real privilege to see Ballengée’s work at Redbud Gallery. It is another example of Redbud showcasing noteworthy and important artists from our region. This exhibition also marks the beginning of Redbud’s new nonprofit status. I look forward to seeing you at Brandon’s specimen drawing workshop on the 25th!

Brandon Ballengée: Sculpting Endless Forms is on view at Redbud Gallery in Houston through February 25.

P.S. I recently read a conversation between two of the most pre-eminent artists of our time, whose works reside at the intersection of art with biology and technology. While debating the premise of an artist remaking nature, one of them insisted that artists “cannot remake nature,” because it is “not selected by evolution” and “evolution happens without us.” The other artist countered that humans have already remade nature, and besides, evolution happens “because of us.” (9).

1. Sanchez, Henry G., “Who are the Houston Bio-Artists?”, Glasstire, May 27, 2019.

2. Anker, Suzanne, “The beginnings and ends of Bio Art”, Artlink, vol 34 no3, 2014.

3. Anker, Suzanne and Flach, Sabine, The Glass Veil: Seven Adventures in Wonderland, ed., Suzanne Anker and Sabine Fach, New York, Art / Knowledge / Theory, Volume 2, Peter Lang AG, 2015.

4. Sanchez, Henry G., The BioArt Bayou-torium, 2019-present.

5. Anker, “The beginnings and ends of Bio Art”

6. Sanchez, The BioArt Bayou-torium,

7. Sanchez, “Who are the Houston Bio-Artists?”

8. Anker and Flach, The Glass Veil

9. Goodeve, Thyrza Nichols, “Where is it, the present? The Three-Body poetics of Suzanne Anker and Frank Gillette”, Strata, Syracuse, New York, Everson Museum of Art, 2021.

****

Henry G. Sanchez is the inaugural Artist in Residence for the Buffalo Bayou Partnership and a regular contributor to Glasstire. Please visit BioArt Bayou-torium and @loccart for news and updates on his current projects.