This article is part two of a multipart series. Click here to read Part One, Part Three, and Part Four.

With just under a couple dozen post office murals to share, to make this road trip more manageable, I’ve divided the series into four different broad regions: West Texas, North Texas, Central Texas, and East Texas. Reminder: we will not be visiting all of the post office murals in each region, just the ones I’ve had the opportunity to view on my travels.

Let’s begin our Texas post office mural journey by traveling west of the DFW metroplex. On the way up to the Texas Panhandle, we’ll make a pitstop in Quanah. As a kid I didn’t think much of the town, through my family drove through it multiple times a year on the way to visit my grandparents in southwest Oklahoma. Today, downtown Quanah feels like the remnants of a former life. But growing up just on the other side of the river from the town, Dad would tell tales about his youthful days in the 1950s and 60s when he would cross the river — the state border — to enjoy Quanah’s nightlife (where he was born, so he can technically qualify as a Texan, right?).

The small Red River town is named for Quanah Parker, the great Comanche chief. Legend has it that on one of his many visits, Chief Quanah Parker declared his blessing on the town: “May the Great Spirit smile on you little town, may the rain fall in season, and the warmth of the sunshine after the rain, may the earth yield bountifully. May peace and contentment be with your children forever.”

Quanah Parker features prominently in the town’s post office mural, painted in 1938 by Texas artist Jerry Bywaters. Bywaters depicted a montage of the town and the region’s history. Front and center is Comanche Chief Quanah Parker facing an Anglo cowboy. In the background roams a herd of American bison near the buttes, known as the “Medicine Mounds,” which the Comanche people still consider to be a sacred site today. Another Anglo cowboy to the left, overlooking a head of cattle, represents the former cattle drives along the nearby Pease River. As your eye moves across the mural, symbols of regional economic development — railroads, mining, agriculture, ranching, manufacturing, and oil — are visible. Every element of the mural is painted in Bywaters’ famous tight brushwork and hard-edged style.

Many of Texas’ post office murals were created in the American Scene style, which was popular in the first half of the 20th century in the U.S. (Art fact: American Scene is the general, umbrella term, whereas regionalism usually refers to rural imagery, and social realism denotes urban or politically-oriented content.) It’s a naturalistic style that often depicted scenes of typical American life and landscapes, popularized by artists like Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood, who were considered to be the three major representatives of that movement. American Scene artists rejected modern trends like abstraction, which were emerging in the art world, and instead adopted academic realism and romanticized portrayals of everyday American life.

In addition to the objectives of the American Scene movement, Texas Regionalists like Bywaters were inspired by the social realism of the Mexican muralist movement, led by the likes of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros (though the Texas post office murals are void of the political content found in the work of their Mexican counterparts). In fact, Bywaters met Rivera during a visit to Mexico in 1928. Bywaters wrote later that year in The Southwest Review, “I know now that art, to be significant, must be a reflection of life; that it must be understandable to the layman; and that it must be part of a people’s thought.”

Bywaters was no layman, but more like a Renaissance man. He was an artist, a professor, a museum director, an art critic, and a historian. Some folks know Bywaters as a founding member of the Lone Star Printmakers or as a member of the Dallas Nine. Others know him for his forty years at Southern Methodist University directing the art and art history departments. Or, there was the two decades (1943-64) where he served as art director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (now the Dallas Museum of Art). And he was an art critic for The Dallas Morning News and a contributing writer for the literary journal Southwest Review. It’s a wonder the man ever had time to paint!

Continuing on US-287 into the Texas Panhandle, we come to the steps of the federal courthouse in downtown Amarillo. Prepare yourself for the granddaddy of the Texas post office murals: six vibrantly colored panels depicting Texas’ history and landscape. Because the mural is in a federal building, you are required to deal with some security measures, such as metal detectors. And yet, once you get through, you will stay where you are, because mounted high in the foyer are the panels, displayed across the top of each wall. Security guards inform you of the strict guidelines: no photographs that include the security equipment; all photographs will be reviewed by said security guards before leaving to ensure guidelines have been followed. Mind you, this is a cramped space. The murals are high and large and the angles are challenging! But you manage.

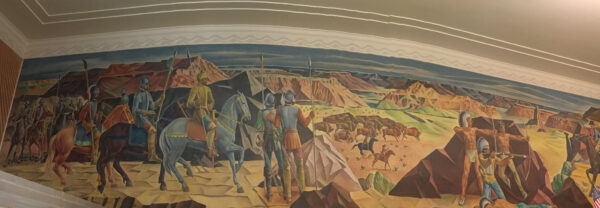

Amarillo, TX. Julius Woeltz, “Coronado’s Exploration Party in Palo Duro Canyon,” 1941 (left side of panel). Photo: Leslie Thompson.

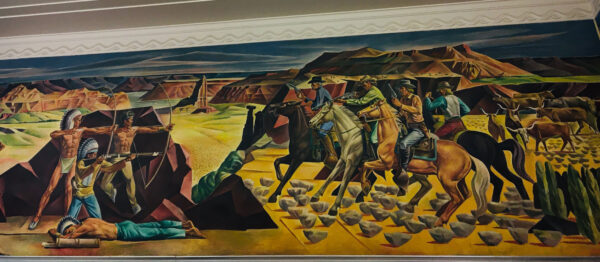

San Antonio artist Julius Woeltz combined the themes of history and human ingenuity for his Amarillo mural. The largest and most notable panel stretches the entire length of a 36 foot wall. Similarly, the subject matter spans quite a length of time, from the 16th century period of Coronado’s exploration in nearby Palo Duro Canyon on his quest for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold, to the late 19th century during the cattle drive era. This is also the era of conflict between Anglo settlers and local Comanche people, depicted in the mural with the two groups embattled in a standoff. Here is where Woeltz’s cubistic style is a little off-putting, with triangular blocks under the horses’ hooves representing the high-plains sage brush. The decorative scene feels like a natural history diorama, a stylized reenactment of the violence and brutality suffered.

Amarillo, TX. Julius Woeltz, “Coronado’s Exploration Party in Palo Duro Canyon,” 1941 (right side of panel). Photo: Leslie Thompson.

Where Woeltz’s cubist-inspired style, with its sharp edges and hard angles, really shines, is in the two smaller murals above the entrance of the federal building, which depict agricultural activity. Gang Plow and Disk Harrow demonstrate the power of machinery and the modernization of agriculture. Cutting into the land with deep, vertically-arranged furrows, the rhythmic lines of the soil and the machines are hypnotizing. The uniformity is a perfectionist’s dream.

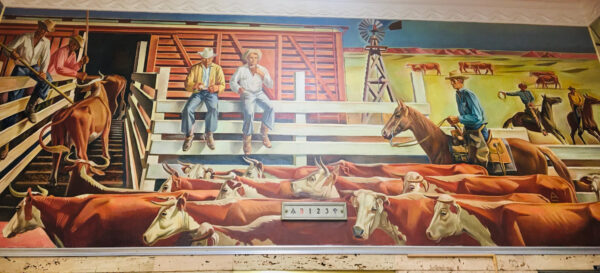

The other three Amarillo panels focus on the development of ranching and oil, two economic staples of the Texas Panhandle. One panel portrays a group of cowboys branding cattle. Another shows livestock boarding railroad cars to be transported to the market. The third panel features the oil industry, with a group of oil workers tending to a drilling rig, an emblem of modernity and “progress.”

Apparently some Amarillo residents took issue with details of the mural, such as the neglection to depict a shipping pen in one of the ranching panels (cattle are never loaded on cars directly from the range). Other remarks included complaints about how the cattle are too clean. One person accused Woeltz of painting English saddles for the cowboys. Woeltz fought back. In an interview with Time magazine, he asserted, “Being no stranger to the West, it is inconceivable for me to have placed an English saddle in a western setting. On many occasions, a western saddle had made an impression upon me that can only be called indelible.” Woeltz had grown up on a ranch!

Julius Woeltz was from San Antonio, where he studied with the well-known early Texas artists José Arpa and Xavier Gonzalez. During his time outside of the state, Woeltz studied at the Académie Julian in Paris, the Art Institute of Chicago, and regularly spent time in Mexico studying the Mexican muralists. Woeltz eventually joined the faculty at Sul Ross State Teachers College (now Sul Ross State University), where he became head of the art department in 1932. The landscape and surrounding mountains (there’s practically a mountain range in every direction) inspired Woeltz and his students, whom he took off campus to practice plein air painting, sometimes traveling down to Big Bend or the Davis Mountains. In 1941, he joined the art faculty at the University of Texas at Austin, where he taught for the next decade (excluding his stint serving in the U.S. Army Air Corps during WWII), before retiring back in San Antonio.

Moving out of the Panhandle, we journey through Anson. This small town has a seemingly innocuous post office mural portraying a group of people dancing together. The artist, Jenne Magafan, was not a Texan. Throughout her life Magafan spent time in Colorado (where she studied with Frank Mechau, who will make a post office mural appearance later in our series), California, and New York. In her search for appropriate subject matter for the Anson mural, she learned about the town’s annual square dance soirée, the “Texas Cowboys’ Christmas Ball.” Sounds harmless, right? Notice the little brown jug in the lower right corner. This tiny detail was the source of great consternation. A local pointed out that Anson was a “dry” town (and still is today). While some found the mural to be a lovely, colorful, “good work of modern art,” others could not get over the “obnoxious liquor jug,” feeling it to be a jab at the community’s upright moral character. Gotta love the public in public art!

Getting back on to I-20, we travel further west through Big Spring, making a pit stop at New Mexico-based artist Peter Hurd’s mural, O Pioneers. The former post office is now a courthouse, which I found to be quiet and empty during my visit. The mural depicts a domestic scene of a pioneer Anglo family working hard to make a good life for themselves in this new land. Today, this is what historians identify as settler colonialism, but in 1938 it was considered to be the emblem of frontier values.

In the background, Hurd incorporated identifiable elements of the local landscape, like Signal Mountain. To further drive home the pioneer values he portrayed, the artist derived the title of the mural from the writings of Walt Whitman, inscribing the referenced line under the painting: “O pioneers, democracy rests finally upon us, and our visions sweep through eternity.” Not only was the mural a success in the eyes of the local townspeople, but Hurd thoroughly enjoyed the experience of painting it. “The experience of painting in the public lobby of a post office was one of the most exciting I have ever had: The crowds that gathered below the scaffold – mostly plainsmen, ranchers, and farmers, with their audible comment was a new experience.”

Just an hour down the road from Big Spring we find ourselves in Odessa. Are you ready for something epic? Of the 23 Texas post office murals I’ve visited thus far, Tom Lea’s 1940 Stampede remains my favorite. The El Paso-based artist captured the intensity of a stampede of longhorn cattle in the middle of a thunderstorm, the quivering line of the lightning bolt in the background emulating the chaos of the herd. Near the center of the action is the lone cowboy thrown off his poor horse (look at the fright in its eyes as it tumbles to the ground!), while the red, glowing eyes of a black steer stare down the viewer. Every time I look at this painting I’m immediately drawn into the drama. Like the storms of West Texas, it comes on quick and strong. It’s an assault on the senses, stimulating my imagination, making me hear the chorus of trampling hooves and crackling thunder.

The way in which the mural is painted adds to its intensity. Lea’s jagged and sharp shadows, his dark edges, and the stark contrast of his highlights of the anatomy of the cattle make a bold statement. The artist first began developing his skills at an early age, eventually studying at the Art Institute of Chicago under John Warner Norton, one of the country’s pioneering muralists. Lea went on to paint murals all over the U.S. and Texas, so many in fact that there is a Tom Lea Trail. When I first viewed his Odessa mural, I found it had been moved to the new downtown post office building. Since then, the mural has moved to the local art museum, where it’s undergone restoration. We’ll see Tom Lea again soon, but first, let’s make another pitstop.

If your journey to Far West Texas takes you to the Big Bend region, you’ll likely pass through Alpine. In his 1940 post office mural, the Spanish-born painter José Moya del Pino captured the mountain ranges surrounding the town and highlighted what the local people identified with most strongly: the influence of the local state college. A female student reads a magazine, a male student behind her reads a book, and even the cowboy on the right reads a newspaper or journal. The post office provided access to all kinds of reading material for everyone, no matter their gender or demographic. Compared to the nostalgically portrayed history found in many of the other Texas post office murals, Alpine’s subject feels almost modern as it moves towards inclusivity.

We end this section of our journey at the farthest tip of West Texas: El Paso. Like Amarillo, this mural is housed in a federal courthouse, ergo the presence of security. Fortunately, these guys are friendly and share fun facts with you, like how you just traversed the same courthouse steps that Johnny Cash graced when he was arrested for smuggling drugs in from Juarez. In the lobby of the federal building, Tom Lea’s 1938 Pass of the North mural looms large due to its size: two panels that each measure 11 x 21 feet. Across these two expansive panels, set against the arid West Texas landscape, the artist narrates the history of El Paso. The left panel starts the timeline with Spanish explorer Coronado. A number of figures appear nearby, such as a Franciscan monk, a fully outfitted vaquero, and a mounted Texas Ranger holding the U.S. flag. Move over to the second panel on the right and you’ll see a continuation of the timeline with a pair of Apache scouts, a couple of Anglo pioneers and settlers, and finally a sheriff, who symbolizes the establishment of law & order.

I told you we’d see Tom Lea again. Representing his hometown, Lea was meticulous about every detail of this mural. The extent of his research and preparation is astounding to read about, which included at one point driving over 1,000 miles to Hollywood to rent a replica of a conquistador’s 16th century armor. Accuracy was paramount. Above the doorway separating the two panels is a painted inscription that speaks to that romantic lens through which Lea viewed his town’s history: “O Pass of the North Now the Old Giants Are Gone We Little Men Live Where Heroes Once Walked the Inviolate Earth.”

As you might have noticed, I really enjoyed visiting each of these seven post office murals in the West Texas region. Let’s meet up next time when we’ll explore some of the murals around North Texas.

3 comments

The Seymour Tx post office has my favorite!

I’d post a picture, but alas, I cannot figure out how to!

I just saw the Odessa mural today. I was disappointed that it was displayed behind glass, which made for a very distracting glare that interfered with enjoyment of the mural. Also, since the article says the piece is being restored, is what I saw a reproduction?

I like what appear to be construction photos in the bulletin boards of the Alpine, Texas photo. When I see these i always stop and take a closer look. Most of these were built by hand which is impressive and worth nothing.

David W. Gates Jr.