Read part one of this conversation series here. Read part two here.

An excerpt from William Bartleson Sr.’s transcribed Will:

“….I bequeth to my wife $140 in money now on hand, also three negros __, Edmund about 24 years, Alsa about 20 years, & Hannah 5 years old. To have and to hold the aforesaid property during her widowhood together with the proceeds thereof. And immediately after her Death or intermarriage (should such take place) the property aforesaid to be sold as my executors may deem best and if she should again marry she is to be entitled to her lawful part of said property and the balance to be equally divided between my children. . . . Also to Hannah my negro girl name Martha at the price one hundred and fifty dollars and a mare at the price of fifty dollars which has been received . . . I further desire that my two negro boys Henry and Jeff shall be sold and the proceeds equally divided between my children.”

William Bartleson Sr. 1770 – 1832 , Rowan Co. NC – Wayne Co, KY

The exhibition To Have and to Hold was originally scheduled to take place at Co-Lab Projects in Austin in 2020, before my tenure as Guest Editor at Glasstire, and before my time as Co-Lab Director. This series of interviews also predates my time as both, and acts as a way to preface the project, by artist Virginia Colwell.

Virginia has an intense research-based practice, much of which begins with her own father’s archive, whose work as an FBI agent intersected with many pivotal points in U.S. history and Latin American intervention. This idiosyncrasy was inherited by Virginia, whose life and genealogy also intersects with many ugly and painful moments of history in our country, and in the State of Texas.

In To Have and to Hold, Virginia explores the danger of southern romanticization, particularly in the landscape, a trait that many of us have also inherited and share.

LMC: The landscape has become a major protagonist in this exhibition, and your research also revealed a little-known history about colonization efforts post Civil War that also factor into your work. Can you tell us about the colony in Veracruz and how that history is represented in the project?

VC: As part of my research into the Civil War period and the Reconstruction era of the American South, I came across this little-known history of numerous Confederate colonies that were established throughout Mexico, Central, and South America. There was a colonization project by a handful of high-ranking Confederates who insisted upon leaving the South and starting new colonies that would perpetuate their southern culture outside the United States. During the Reconstruction period, the lands that belonged to these people would have been confiscated and broken up by the Northern government as part of the Reconstruction laws.

At that point in time, some people thought they had no place within the new southern society, and with great arrogance, they decided they could just pack up and move to another country and establish new “mini-souths,” some of which were actually successful. There’s one in Brazil that celebrates colonial festivities to this day, and residents dress up in antebellum fashion as a way of honoring their ancestors. There was also one colony that was started in Veracruz, Mexico, and I decided to go there to see the place, or at least see what vestiges of the colony are still there.

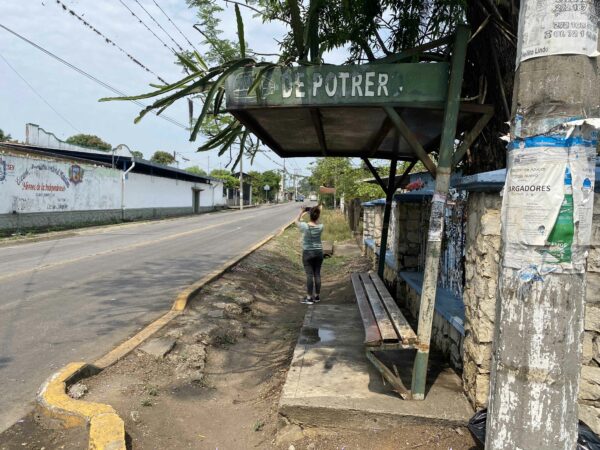

Like much of the Southern United States, Veracruz is an area with a tremendous amount of humidity — perfect for sugar cane and rice production. And like much of the deep South, the landscape is covered in a tremendous amount of vegetation — lots of bromeliads, massive trees, and Spanish moss. When they came to Veracruz, the colonists would have seen a landscape and an agriculture that was quite similar to what they had in the American South.

What interested me was that despite all the research I’ve done, and despite my academic and informed eye, I still couldn’t shake this loving romanticism of the iconography of the South when I saw the Spanish moss and the ball moss inundating the telephone lines and electrical cables of Veracruz. This romanticism is seemingly harmless and has been cultivated in many people, myself included. It’s a sort of sentimentality toward the lazy vegetation that sways in the breeze and covers everything in thick green, and it’s an intrinsic part of southern identity.

LMC: As a native Texan, I can also account for the fact that we certainly hold onto the mythology of our southern state. It colors much of our own culture and certainly defines us in many ways. What did you find in Veracruz?

VC: While I was in Veracruz, I had the feeling of being in a similar landscape to the American South, and that similar feeling of romanticism which is completely without basis. I started to think about that unshakable romanticism, this way of idealizing and loving a narrative that has been constructed in a way that aims specifically to erase the histories of that landscape, or to ignore them or cover them up in the same ways that a tree covered in Spanish moss and bromeliads is suffocated.

There aren’t any vestiges left of the colony in Veracruz. That history sort of came and went and left very little trace, and certainly no permanent trace, image, or structure. The lack of a trace made me think a lot about history, and how history has very few vestiges, very few ruins. This topic is one I touch on in a lot of other works — this absence of the past in a landscape. In Veracruz, there was a sense of romanticism in absence that captured my attention and made me think about the same romanticism in absence that exists in the American South.

LMC: How did this manifest in your work?

VC: The second piece in the exhibition, without shadow of sympathy, is an installation that is meant to replicate elements of the landscape. There was a disparaging and cynical report published about the arrogance of the colonists who traveled to Veracruz and thought they could start a colony. People went with dreams of transplanting the South someplace else, and there was a tremendous amount of misinformation and land speculation, and it was all an abject failure. The piece is titled after the words the writer of the report used to criticize the people who unscrupulously encouraged colonization, who promoted a fanciful Arcadia where a new confederacy could be reborn.

The work I made is a replica of the Spanish moss and ball moss that I saw covering the telephone wires and electrical cables in Veracruz. The pieces are done in brass, which was tediously cut, formed, and hand soldered. In the gallery space the pieces are a beautiful, shiny, swaying symbol of Southern romanticism. That said, I also wanted to comment on the deception involved in that romantic narrative of the South, so the flowers have surgical blades peeking out from beneath their petals. From afar you don’t notice them, you just see a glint in the pieces, but when you get close you notice those very, very sharp blades that are intended to cut human skin. It was my way of remarking on the harm and violence done by this romantic view of the South and the sentimentality we have cultivated around the southern landscape.

Process image of surgical blades between brass leaves for Virginia Colwell’s installation at Co-Lab Projects.

LMC: Over the years you and I have talked a lot about the context of this exhibition — the context of the state of Texas, and specifically, the city of Austin, which has seen dramatic change and subsequent historical erasure in tandem with its gentrification. What is the connection to Texas within To Have and to Hold?

VC: Like many southern families, mine also started to move west as land was appropriated. I believe they first went to Kentucky, then to Grayson County, Texas where they were prior to and after the Civil War. That is actually a part of my family history that I don’t know as much about, and where it becomes more challenging to trace the thread of white supremacy.

However, Grayson is where the lynching of George Hughes happened in 1930, which was a horrendous incident and the subject of the sculpture Death, made by Isamu Noguchi in 1934. But, after the Civil War, the family traces went quiet and researching them will require going to Texas archives in person. Due to the pandemic and other life events, I haven’t been able to continue that part of my research, but I want to study more about Grayson and the Reconstruction period in that area in order to try to identify how my family was involved, or see how they showed up in the archives.

Process image of brass replicas of ball moss for Virginia Colwell’s installation at Co-Lab Projects.

LMC: Your family and family history has been a central point of departure for this project and exhibition. How does the title, To Have and to Hold, reflect that as well?

VC: The title of the exhibition comes from the will of one of my ancestors from Kentucky. The will designated the man’s slaves to his wife by saying, “to have and to hold for the rest of her life.” I was taken by that phrase because it’s normally said in marriage vows.

I didn’t realize the same language was also applied to enslaving people. I guess you could say that those words kept tumbling around in my head because they have so many implications that go with them. They are both a completely unexpected and very obvious way of describing slavery and the relationship between slaves and their slave owners. But they also are relevant to my relationship to this research, these documents, this history — what does it mean to hold this history close, what does it mean to have this history?

LMC: What are you taking away from the research and project, at least in this phase of it?

VC: I think it’s important that things related to this project do not end with the Civil War. There’s been a lot of work done in recent years to show the ongoing reincarnations of severe segregation, oppression, slavery, and racism in American culture, governance, and American history. But normally there’s a jump from the Civil War to the Civil Rights movement, overlooking the one hundred years in between. These years deserve more study and consideration.

*****

This is the third in a series of interviews preceding the opening of To Have and to Hold at Co-Lab Projects in Austin. The exhibition, which is supported by the Jumex Foundation, will open on January 28, from 8-11pm and will run through March 4, 2023.

Thank you to Austin Nelsen, Chris Burch, Vladimir Mejia, Adrian Aguilera, Jacqueline Overby, Omar Barquet, Ian Barquet Colwell, Sean Gaulager, Christine Gwillim, the entire team at Glasstire, and super super special big thanks to Chris Tomlinson.