Read part one of this conversation series here.

Virginia Colwell’s exhibition To Have and to Hold has been in process for the better part of five years, during a time in which our world has faced, seemingly simultaneously, both collective and divergent challenges. The research involved — and the final project itself — reflects the many changes and obstacles that have influenced Virginia’s research, and the final installation itself looks at the romanticisation of the Southern landscape.

Virginia’s research takes many twists and turns, and I was interested in her research-based projects that often begin with her own father’s archive, which was left to her after his passing. This archive is unique and intersects with significant moments in both United States and Latin American history, often illustrating the deep ties of U.S. intervention in Latin America itself.

While To Have and to Hold predates my time as both Co-Lab Director and my tenure as Glasstire Guest Editor, this series of interviews was planned to preface her upcoming exhibition at Co-Lab Projects, to offer insight into her rigorous research process, and to examine the ways in which her own genealogy has intersected with ugly and painful moments of U.S. history.

To read the first interview this series, go here.

Leslie Moody Castro (LMC): Time and labor have been a sort of undercurrent in your work, and your upcoming project, To Have and to Hold, is definitely another example of that. But I also think the way the work challenges the truths that we apply to history is another important component of it. You meticulously deconstruct the idea that histories are both linear and fixed, but what’s also really interesting is how your own family history collides with major historical events. To Have and to Hold is such a great example of that.

Virginia Colwell (VC): The project began with this desire to link up different parts of my family history and research the line between those two points in depth. I had a memory from when I was little where someone said something about my family having house slaves at some point in time, and I also knew that parts of my family were some of the first colonists in Jamestown. I started thinking about the enterprise of colonization in the United States and was curious about how much I could document my own family’s interaction with and perpetuation of the institution of slavery.

LMC: Speaking of time, To Have and to Hold has been in the works for a while. Can you elaborate on how this project started?

VC: I mentioned my own family’s connection with Jamestown, but the second part of that is the involvement with my father’s archive. Over the years, I have researched several African American men that my father arrested for bank robbery — which was a federal crime — in the early 1970s, when he was an FBI agent in Richmond, Virginia. He saved their mugshots, which were then passed onto me in his general archive. I have been really curious about these mugshots for many reasons. I wanted to know who these men were, aside from the supposed crimes they committed, and I wanted to know why my father saved these images, because they’re macabre souvenirs of the people whom he deprived of their liberty. That moment when the photo was taken changed the course of their lives, at least in the short term.

I also think it’s important to consider the climate in which my father was working at the time. In the early 1970s, the Civil Rights movement had certain gains and school systems in the south reluctantly started to integrate by bussing students in, but it was also a time of white flight from the cities, which just repeated many of the same systems of segregation. This was all happening when my father would have arrested these men. I’ve been very leery of these images because they are souvenirs that served as a memento of somebody’s entrapment, and what the FBI, justice department, and policing in general was doing in African American communities.

The justice department saw itself as a bastion against civil rights in many ways — it was and still is a very conservative institution. These activities are now seen to be another face of white supremacy and the ongoing repression that has its earliest roots in the institution of slavery in both Virginia and the United States. So I wanted to see if I could trace how my family interacted with this very southern manifestation of white supremacy, from that first colony in Jamestown to my father arresting African American men for bank robbery.

LMC: What were some of the initial conversations like when you started this research?

VC: It’s actually hard to remember, because I started this research in earnest back in 2017 or 2018. At that point in time Trump was in office, and around the time when I started to really delve deeper, Charlottesville happened. But there still wasn’t as much talk about white supremacy, historical oppression, and reparations as there has been since the death of George Floyd, the protests that followed, and the Black Lives Matter movement, which my research also coincided with.

What I do remember is that I was asked by many people why I would want to look into this stuff, and why I thought it was important, and what I thought would be the end result of this kind of research. Their subtext always alluded to the bigger question of “what is the value of tracing all the horrible ways in which my family acted as slave owners?”

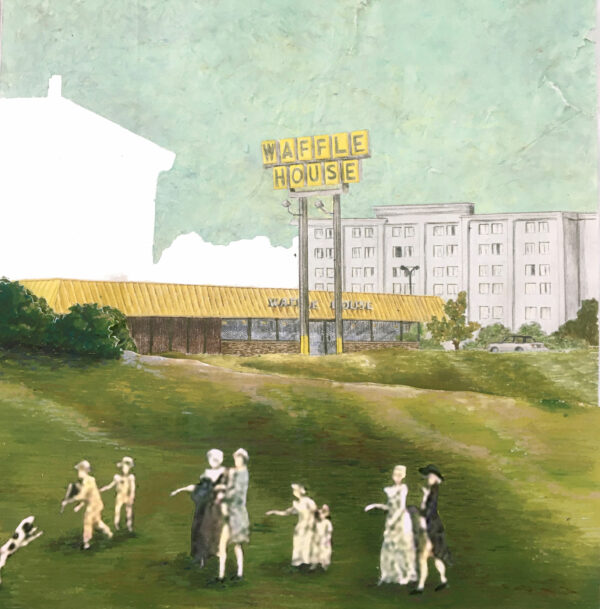

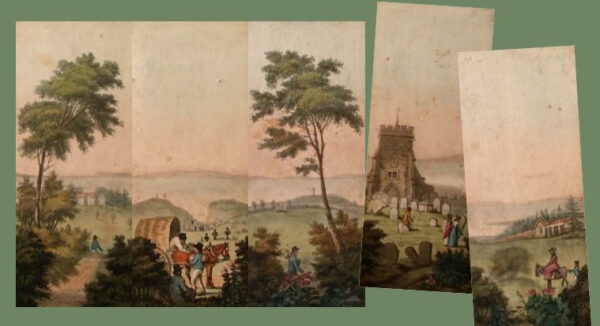

A process detail of “Myriorama” by Virginia Colwell. The finished work is on view in “To Have and to Hold” at Co-Lab Projects.

LMC: And what did you learn through those conversations?

VC: It really depends on who I am talking to. When I talk with other white people, they offer a sort of congratulatory sentiment for doing this kind of research, then in the same breath they assert that their own families weren’t slave holders. This could be true, but when you start doing genealogical research, you realize the quantity of families you are researching — it comes out to thousands and thousands of people — and it’s hard to defend the idea that slavery did not touch a majority of people from the United States.

There is also a sense of wanting to distance oneself from the possibility that their family is equally as culpable as mine. There’s also reactive questioning of what this research is owed, like the argument that we are not responsible for the “sins of our fathers,” for example. I think the most disconcerting thing is the blithe innocence of our own history, which keeps us from really understanding the depths and breadth of slavery in the United States.

LMC: Can you unpack that further?

VC: The United States has had many, many more years of slavery than it has had without. Add to that the years of overt oppression in both the north and the south. There’s this sense that what I am doing is unique, or that it’s a small project, representative of only my family. In actuality, the slaveholding in the 12 generations of my family is quite representative of many families in the United States in general. The fact is that it’s not something many white people question, and that easy denial has been built into our historical narrative, is disconcerting. Our genealogical memories are so short that something that happened 200 years ago doesn’t seem particularly pertinent.

It’s also been interesting to do the research and see how other researchers on genealogical sites omit that register of slavery. To say it’s a shame is an understatement, because tracing the ancestry of many African American people is through the wills and deeds of white slave owners. If that evidence is edited, hidden, or obfuscated by the descendents of those people, then it hinders others from tracing their own genealogy. It comes down to the fact that even genealogical research sites perpetuate the erasure of people and the incredibly intricate history between African American history and white history.

LMC: Let’s get back to the project a little bit. Can you describe the collages/drawings and their references?

VC: There are two new works in To Have and to Hold. One is a series of landscapes entitled Myriorama, and the other is a large-scale installation sculpture. Myriorama takes its name from a nineteenth-century parlor and children’s game, which was a series of cards that, when put side by side, created a continuous landscape. The cards could be shuffled, which changed their order and changed the narrative of the images, according to their order. Myrioramas usually illustrated landscape scenes of different colonies, or of ruins in Italy. This game is indicative of the Romantic period, when there was great interest in Western European civilization in Europe, as well as the projection of that civilization in the colonies. The myrioramas in and of themselves are an idealized perspective of power over the landscape, and they literally play with the idea of control of the image of the landscape.

In terms of content, Myriorama deals with the representation of the landscape in the American South, starting with the colonial period and up through the present day — the works are a literal collage of different time periods. I became interested in the representation of the American South from the early colonial period up to the Civil War. In my research, I found it curious that there is very little representation of slavery, considering that it is an extraordinarily predominant and economically crucial part of southern culture, and despite the fact that landscape paintings were normally commissioned by the landowners themselves.

Whereas, when British or French colonial landowners commissioned paintings, they would often depict their large labor forces, albeit with the narcissistic undertone of illustrating wealth. I find it really peculiar that this editing and disinterest in representing the full system of slavery existed really early on in the American South. Even today, we have sparse representation of the slaveholding system, which perpetuates disinterest and naïveté about the scale of slaveholding in the U.S., and its central contribution to America’s historical power and wealth.

A process detail of “Myriorama” by Virginia Colwell. The finished work is on view in “To Have and to Hold” at Co-Lab Projects.

LMC: How do you put all this together into Myriorama?

VC: My landscapes mix digital images taken from colonial paintings, which were usually done by self-taught painters and are characterized by a simplicity to the depiction of the landscape. Very often they show typical western tropes of composition and perspective, and they illustrate grandeur through long, sloping pastures and portraits of the landowners strolling their property. I took fragments from these paintings and mixed them with fragments from contemporary landscapes, specifically the those of the land held by my slave-owning ancestors.

I could easily trace which lands my family held because they show up in early British colonial deeds. An early colonial land holder would be given a land deed for the number of new colonists that they paid passage for, the majority of whom were indentured servants. I was able to find mu family’s land holdings on Google Maps, and used the Street View as a way of traveling through them. Myriorama combines Google images of the contemporary views of my ancestors’ land, mixed with the colonial paintings of southern plantations.

A process detail of “Myriorama” by Virginia Colwell. The finished work is on view in “To Have and to Hold” at Co-Lab Projects.

LMC: What really pulled you back to the landscape, specifically?

VC: What interested me was that, despite all the research I’ve done, and despite my academic and informed eye, I couldn’t shake the sentimental romanticism of the iconography of the south, which has been cultivated by our culture and cultivated within myself. It’s the way the lazy vegetation sways in the breeze and covers everything in thick green. I started to think about the unshakable idealizing and loving of a landscape through a narrative that has been constructed and that specifically aims to erase the histories of that landscape.

*****

This is the second in a series of three interviews preceding the opening of To Have and to Hold at Co-Lab Projects in Austin. The exhibition will open on January 28, from 8-11 PM, and will run through March 4, 2023. A public conversation around the show will happen on January 26 at Distribution Hall (1500 E. 4th Street, Austin, TX).