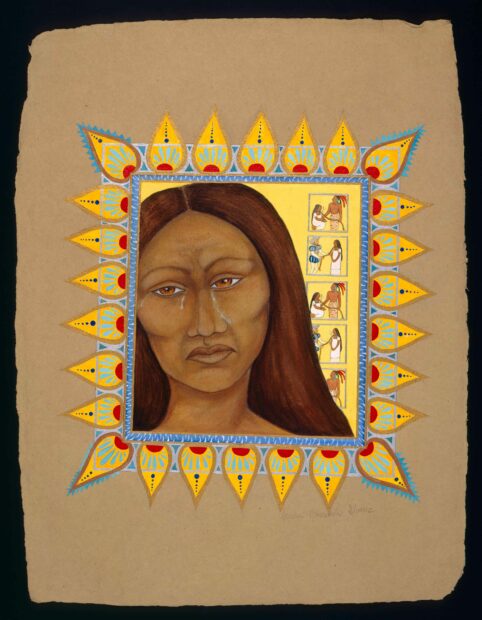

Cecilia Concepción Álvarez (Chicana, born 1950), “La Malinche Tenía Sus Razones (La Malinche had her reasons),” 1995, acrylic paint on Indian paper, 34 ½ x 27 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Cecilia Concepción Álvarez.

La Malinche’s story is one of transitioning power that has been usurped, weaponized, latent, transformed, and harnessed from the 16th century to the present day. The approximately 70 artworks on display in Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche at the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA) introduces these shifting modes of power in all their glory and repulse.

The exhibition’s third rendition reaches San Antonio after opening at the Denver Art Museum (DAM) and traveling to Albuquerque, New Mexico earlier this year. Brought together by DAM and collaboratively curated by Victoria Lyall, the Jan and Frederick Mayer Curator of Art of the Ancient Americas at DAM, and Terezita Romo, an independent curator, Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche is presented at SAMA by Associate Curator of Latin American Art, Lucía Abramovich Sánchez.

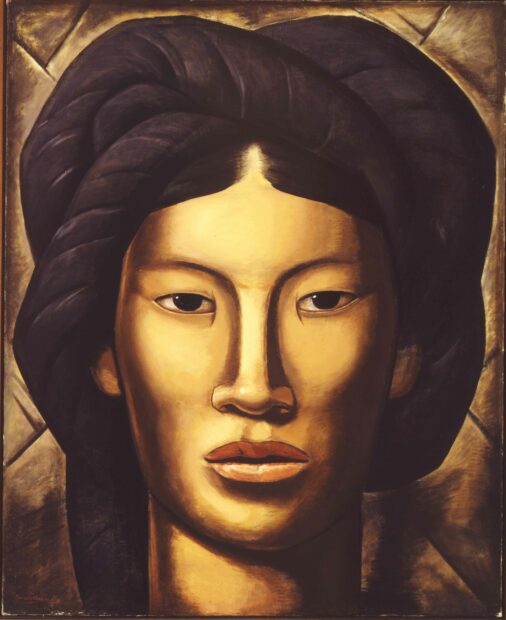

Alfredo Ramos Martínez (Mexican, 1871-1946), “La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca),” 1940, oil paint on canvas, 50 x 40 ½ inches. Phoenix Art Museum; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Friends of Mexican Art, 1979.86. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

With five distinct sections, the show is separated according to different created narratives and identities that have been assigned to Malinche over the years. These five thematic sections include La Lengua/The Interpreter, La Indígena/The Indigenous Woman, La Madre del Mestizaje/The Mother of a Mixed Race, La Traidora/The Traitor, and “Chicana”/Contemporary Reclamations.

The sweeping survey accounts for the nuances in reception and changing historical narratives surrounding La Malinche that have been told between 1519 — when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men landed in present-day Mexico — and the current, contemporary period. The exhibition references Malinche as the iconic mother of mestizo people with mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. But the question remains: who was La Malinche and what led to her status as an icon?

La Malinche, also known as Malinalli, Malintzin, and Doña Marina, was an indigenous woman living during the height of the Aztec Empire. Malinche was sold into slavery by her mother and was eventually given to Cortés. Since she spoke both Mayan and Nahuatl, Cortés quickly realized La Malinche’s value and used her as an intermediary tool. He had her learn Spanish and translate communications between Indigenous rulers and Spanish conquistadors.

Jesús Helguera (Mexican, 1910–71), “La Malinche,” 1941, oil paint on canvas, 6 feet 9 inches x 5 feet. 7 inches. Colaboración de Carolina Performance, una empresa socialmente responsable que tiene como misión la preservación del patrimonio cultural de su país, y la Familia Quintana Corral, en honor a las raíces y el mestizaje de nuestro pueblo mexicano. (A collaboration between Carolina Performance, a socially responsible company whose mission is to preserve the cultural heritage of their country, and the Quintana Corral Family, in honor of the roots and mixed-race heritage of our Mexican people). © and courtesy of Calendarios Landin.

Since she was forced to converted to Christianity and made to have Cortés’s first-born son, some see Malinche as a woman who betrayed her own people. This view was popularized in Octavio Paz’s 1950 essay “Sons of La Malinche.” Similar ideas of Malinche’s status as a traitor are further explored in the La Traidora/The Traitor section of the exhibition. It is important to remember that Malinche was Cortés’s enslaved concubine in addition to serving as his translator, and thus had little freedom.

Cortés and Malinche’s child is the reason Malinche is regarded as a motherly, or Eve-like figure at the head of the mestizo race. This aspect of Malinche’s inherited identity is highlighted in one of the five sections of the exhibition, titled La Madre del Mestizaje/The Mother of a Mixed Race.

As a force uniting two distinct cultures through her communications, Malinche’s role as translator is emphasized in the first section of the exhibition, La Lengua/The Interpreter. Take for instance Armando Baeza’s La Marina/La Malinche bronze sculpture greeting visitors upon their entrance into the exhibition space. The sculpture depicts La Malinche balancing on one foot with outstretched open arms and palms face-up. Her welcoming embrace is emblematic of Christ-like postures, such as that of the Christ the Redeemer sculpture in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Although potentially emitting a sense of Christ-like love and acceptance, this sculpture of La Malinche is distinct in its fluidity and emphasis on aspects of the female body, such as her pronounced hips. Additionally, her downcast gaze alludes to her forced passivity and conversion to Christianity.

Emanuel Martinez (Chicano, born 1947), “La Malinche,” 1987, bronze; 15 x 17 x 13 inches. The Abarca Family Collection, Denver. © Emanuel Martinez. Photo © Denver Art Museum.

Malinche’s forced passivity is turned around in Robert C. Buitrón’s black and white photograph included in the same section. Malinche y Pocahontas Chismeando con PowerBooks (Malinche and Pocahontas gossiping with PowerBooks) reimagines a conversation between Pocahontas and Malinche, as they are pictured in the foreground of the image talking across a table and typing on laptops in a coffee shop in 1995. Out of focus in the background are three men who act as subsidiary characters in the unfolding narrative. Whereas men such as Cortés and Moctezuma II are often in the foreground of historical narratives about Spanish conquests in America, this photograph instead focuses the view on the women who have largely been pushed into the shadows of history’s backdrop. It also provides a vision of these women in charge of writing their own stories from their own perspective, something La Malinche and Pocahontas never had the opportunity to do. It disrupts their victimization and turns them into active participants, while also highlighting the important use of language in each of their stories. The self-determined language depicted in this image is especially significant because history has largely been recorded, written, and passed on by men. Over time, stories of indigenous women such as La Malinche and Pocahontas have often suffered from being twisted, romanticized, and embellished.

La Malinche’s story is further monumentalized in Jesús Helguera’s large-scale history painting, La Malinche. Painted in 1941 and included in the La Indígena/The Indigenous Woman section of the exhibition, the work depicts Malinche in the arms of Cortés, sitting on the side of a horse, and looking out towards the viewer. With one hand, Malinche fingers her cross necklace, and with the other, her huipil (tunic). Her huipil, braided hair and sandals serve as an expression of Malinche’s indigenous identity, while her fair-colored skin and cross necklace draw attention to her complicated role in Cortés’s conversion and colonization scheme. The complex combination of identity markers in the image paint Malinche as both a notorious and celebrated figure, parallelling the trajectory of her historical reception.

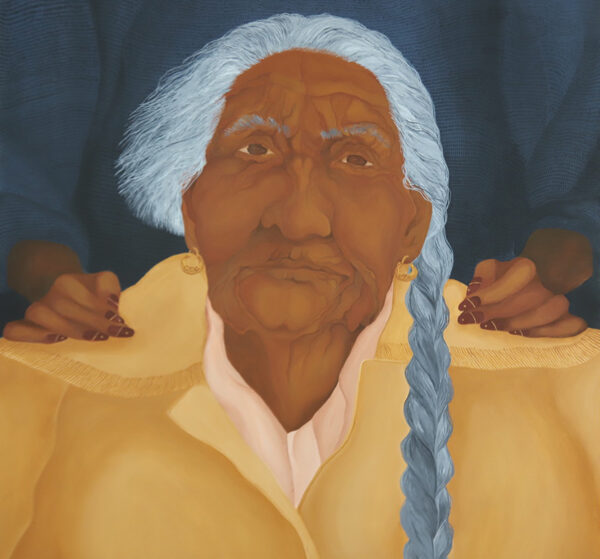

Gloria Osuna Pérez (Mexican American, 1947–99), “La Malinche,” 1994, acrylic paint on canvas; 30 x 30 in. Collection of Xoxi Nayapiltzin. © and courtesy the estate of Gloria Osuna Pérez.

The artworks included in the last section of the exhibition, “Chicana”/Contemporary Reclamations, work to re-write Malinche’s historical significance. Gloria Osuna Pérez’s 1994 painting, La Malinche, envisions how Malinche would look as an older woman. In reality, Malinche only lived to be about 30 years old. Complete with wrinkled skin and gray hair, Pérez’s elderly Malinche embodies the contradictory nature of her life and her legacy. One side of her hair is depicted in a long, gray braid that continues out of the frame, while the other side of her hair is cut short, barely reaching below the top of her ear. This slashing off of one side of Malinche’s hair serves as a physical depiction of her antithetical experience and the wounds that were inflicted on her and her people. Still, Pérez’s elderly Malinche retains a pleasant look on her face, and her eyes slightly face upwards casting a gaze of hope and peace.

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche provides a comprehensive account of Malinche’s historical significance and role in global politics. With artworks made using a range of materials by nearly 40 artists from across Mexico and the United States, La Malinche’s story is illuminated, questioned, and reinterpreted to fit contemporary understandings of mestizo identity, the Spanish invasion in the Americas, and the unfortunate fall of the Aztec Empire.

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche is on-view at the San Antonio Museum of Art through January 8, 2023.