Jamie Robertson’s work embodies an Octavia Butler saying: “The more personal the more universal.” Through lens-based media, Robertson uses her familial archive to explore intimate and collective histories and their fascia to the African Diaspora. Rooted in the Gulf South, Robertson’s work invites viewers to think of their own archive, and perhaps their definitions of lineage, in an ever-expansive world.

In this interview, we not only discuss her practice, but also her extensive research and the three (now four) shows in which she has work on view in Houston and Galveston this fall.

Carris Adams (CA): Jamie, we have so much to discuss. But let’s begin with how you came to make this work. How or when did you decide to dive into your archive and use it as a medium?

Jamie V. Robertson (JVR): The family album is your first archive. I’ve always been interested in my family history. I’ve been doing genealogical research on my mother’s side of the family for years. I’ve used several websites, such as www.findagrave.com (a morbid name but it gets to the point), to help me locate people that have the same last name or names as those within my family. So this work began with family albums and looking at cemeteries to find my ancestors.

In addition to family research, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s monograph of Daufuskie Island was instrumental in my picking up the camera. She spent ten years in South Carolina, photographing the Gullah Geechee people on the island and noting how the island was rapidly changing. I brought that book home to show my mom while I was in undergrad and she said, “This looks like where we’re from.” While she grew up in Texas and these images are off the coast of South Carolina, my mother was speaking about the aesthetic of the images; the way the houses look, the images of people going to church, etc. This monograph boldly stated to me that Black life in the rural south is worth documenting and preserving. There is not a lot of representation of Black people in general, but what we do have tends to be more regionally specific, centering on the experiences of Black people on the East and West coasts and larger cities such as Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, etc.

I felt it was important to document and discuss the space/place from a rural town that you bring with you to a major city and the back and forth that comes with it. Being in Houston, there are many areas that feel like you’re in a small town, so we’re never far from our roots.

CA: Absolutely. There are whole sections of this city that feel like small towns because the city has woefully neglected areas and forced them to be sustainable in their own way, much like rural spaces. The images of Black people in rural spaces we see are typically old and meant to represent a long and distant past. There is the idea that your great greats lived there — it’s hot, slow, and has no air conditioning. It’s often seen as tragic, “can’t get right,” and precarious.

Jamie Robertson, installation View of “A Hundred More” at Galveston Art Center. Image Credit Roxann Grover.

JVR: Oh yes! Lots of traumatic narratives of murder, land being stolen, and the like. And of course, these things happened, but it is not the only narrative. My family is from several towns within Leon County, some incorporated and some not, and they have held land there for over 140 years. This inspired my show, titled A Hundred More,at the Galveston Arts Center. I have a lot of anxiety and other feelings about what will happen to this land and the dwellings that are on it, such as my great-grandmother’s home. This is a second home to me and a part of my identity as a Black Texan.

CA: When I look at your work, it makes me think of Black Feminist Hauntology and what Toni Morrison coined as rememory, which is the ability to recollect, remember, and construct a different reality or realities from a traumatic experience. Black Feminist Hauntology, literally and figuratively, speaks to how these ghosts are embedded in the land. At the same time, I also see a reverence for your elders and ancestors who have come before you. Can you speak to any connective threads between Black Feminist Hauntology, rememory, and familial pride?

JVR: My work is leaning fully into these things. I believe there is power in the land, as my ancestors are buried there and this power is also in me. There are things that cannot be seen, yet we feel them.

My great-grandfather’s house was a place that I went in search of during the final year of my MFA program. I had a photo of my great-grandmother’s house and I felt it needed, or I needed, the companion image. So I went looking for his house in the unincorporated town of Hopewell. Me and my mom drove through the woods with my grandmother as she helped us navigate these old roads until we couldn’t drive anymore. I took 3-4 images before we had to leave. And still, I felt a presence there and I can feel that presence in the images even after they were printed.

Often when I am “up home,” as my grandfather used to say, I find myself remembering things that I am not sure are my memories. I have vivid dreams when I’m in the Egypt community in Texas that feel real and I have to ask family members that appear in these dreams whether or not they are real memories or indeed dreams. Things like, “Is this someone else’s memory? Or is this an ancestral memory?”

Jamie Robertson, detail view of “Love is a House that Death Can’t Knock Down,” 2022, installation view at Lawndale Art Center. Image courtesy Ronald Jones.

CA: Do you see yourself and your work as a vessel for the non-waking world?

JVR: Yes, I think so. When I was completing my MFA, I studied Robert Farris Thompson, specifically The Flash of the Spirit, and actual African philosophers, who wrote about spirituality and ritual aspects of the cultural practices in West Central Africa. Many of the people in this region were trafficked to the United States and brought to the Carolinas. I’ve been able to trace some of my family back to those states during enslavement. Many of the cultural practices and rituals that make up African American culture come from that region and the people who were brought there.

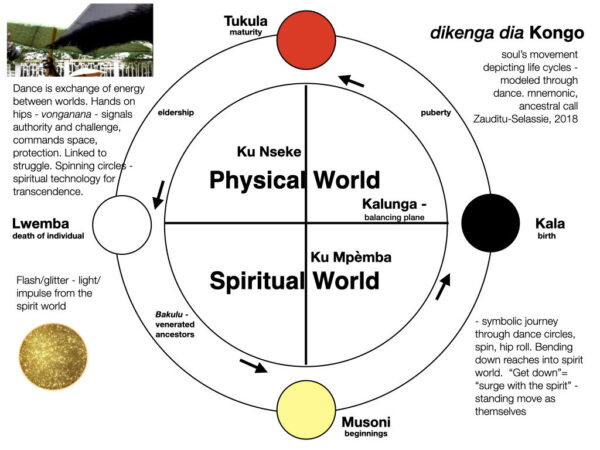

CA: Like cosmograms, for instance. Not only are you influenced by them, but you seem to use them as a guiding principle for the work. There are several different kinds of cosmograms, however, the Dikenga makes several appearances. Can you describe them and why you are attracted to them?

JVR: I happened across Dikenga after Sebastien Boncy posted a link to Khalil Joseph’s short film Until the Quiet Comes. It was the first time I’d ever seen anything like this and it was very moving. In three minutes, so much happens as Joseph speaks to spirituality and time. Duane Deterville writes about how Joseph accesses the Afriscape in this video piece. The cosmogram makes an appearance in the video. Between Deterville, Joseph, and Thompson it felt kismet that this symbol was showing up over and over again in my research. Dikenga di Kongo was demanding my attention. I leaned more into understanding what it is.

A cosmogram is a symbol, but it’s much more than that. Like any symbol, it is a container for a variety of meanings, beliefs, and stories. Dikenga is a philosophy, a belief system, that is living and moving at all times. Two lines intersect in the middle of a circle to form a cross. Each point of the cross represents the cardinal directions and the directions of the sun, thus moving counterclockwise. When you really think about it, moving with the sun is natural as it moves from east to west. The western world has tried to wield time and make it move clockwise as if time is something to dominate. In the West, time is oppressive but that wasn’t the case with this symbol.

I thought a lot about how to incorporate this into the work, and ultimately I incorporated it into my framework of making. For example, I organized my photographs from night to day and the accompanying sculpture, Dikenga Interpretation 1, at Galveston Arts Center, is my own cosmogram. It is inspired by African American yard art and the collection of objects often found adorning one’s yard. The piece is composed of a mound of red clay soil from near my great-grandmother’s house. There is a sea shell in the center of four clocks, representing kalunga. The center line, kalunga, is often represented by water — it divides the physical and spiritual world. There are also the four clocks, stripped to the second hand and moving counterclockwise, representing the phases of the sun (Kala, Tukula, Luvemba, and Musoni).

Dikenga dia Kongo

CA: I’ve been trying to graph your practice. I love graphs as a way to organize my thoughts, and perhaps my life. So I drew a graph to understand your practice between the three major points of land, descendants, and image. What would your work look like as its own graph or system?

JVR: That’s a great question. I agree with what you’ve drafted. It is definitely a circle. Maybe even a spiral, as I began to slowly move out of the personal to the collective.

CA: Exactly. Like many spiritualities and religions, there is an idea that we continue on in some other state, to some other place. For the Dikenga, it is believed that you circle back through life. I see your work as a continuous circle in experimenting with image, adding to the archive, or using the familial to create counter-narratives, and back again. Do you see this work as ever being complete?

JVR: I do not see it as ever complete. I think of it more as volumes. This current volume begins with my great-grandparents as anchor points. There are still things to investigate and document. Recently, I’ve started to move out into the general collective of the Gulf South, about southern history as it relates to the African Diaspora and the land.

CA: This pretty much sums up your work at the Galveston Arts Center. Let’s discuss your shows at Lawndale. You are in two shows: Love Is A House That Even Death Can’t Knock Down and Lo que me queda de tu amor (what’s left of your love).

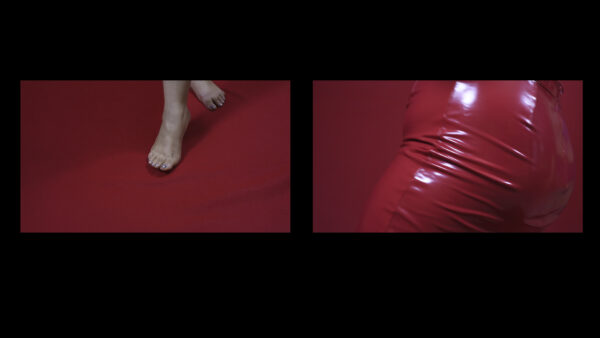

JVR: Lo que me queda tu amor was curated by Francis Almendárez & Mary Montenegro and “considers how artists from distinct backgrounds pass on personal, familial, and communal histories.” I have a video work in the show titled Flat Red, where I dance in a red skirt, barefoot, against a red background. I danced for 2-3 hours to a variety of music (cumbia, hip hop, R&B, etc). In post-production, I originally edited the video without sound. At the very end, I added Coupe Cumbia, a track by Chief Boima from an old free music compilation download from 2010 called Banana Clipz.

Coupe Cumbia is this sonic fusion of two places. It takes the Coupé-décalé, from the Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa, and blends it with Cumbia from Colombia in South America. Both of these genres are part of the African diaspora, with Cumbia being a sound with shared origins in African and Amerindian communities. The latter is extremely popular in Houston. It’s a staple in Houston’s music scene, with DJs often mixing it with other genres in one night.

Jamie Robertson, “Flat Red,” 2019, video image still. Image courtesy Jamie Robertson.

CA: In Flat Red, the viewer only sees from your hips down —mostly hips and feet. You don’t appear much in your work. Can you speak to this choice?

JVR: I think of Flat Red as an extension of the self-portraiture I started in grad school. Because my body is fragmented in the video, I think the skirt kind of takes on a life of its own. In grad school, I was making self-portraits as a way to document myself and embody ideas of Black womanhood. But I was unsure of how those things were being received, and also, I felt stuck. A self-portrait as a moving image feels really different from a still image.

CA: Lastly, we have Love is a House…

JVR: That Even Death Can’t Knock Down. This is a group show curated by mk, Irene Antonia Diane Reece, and myself. Each of us use our family archive to address themes of life, death, and memory in relation to a Southern Black experience. My work in the show is one of the first times where I break away from the frame. While there are a few frames that make an appearance, the prints are larger and I have begun collaging family photographs on top of my photographs. This creative decision puts the family archive on an equal playing field with fine art photography.

Jamie Robertson, “Love is a House that Death Can’t Knock Down,” 2022, installation view at Lawndale Art Center. Image courtesy Ronald Jones.

CA: It seems that the entire show is a memorial of sorts and an ode to the love for family.

JVR: Exactly. How do you pay respects to those that have come before? A literal example of this in my work in the exhibition is the video piece, Dusting. It is a single-channel video of my grandmother Verna tending to my grandfather’s grave. This labor of love is repeated over and over as an act of reverence for the dead and a reactivation of memory.

CA: Interestingly, you all are referencing the Dikenga, specifically death, the heating and cooling of existence, and the return to the physical world. I once read that “time does not pass, but accumulates.” So my last question is, what do you hope your work passes on to viewers? And while your work doesn’t make sense to be purchased, what is passed on if the work is collected?

JVR: I don’t see this work being collected in the traditional sense. I did publish a book and that feels different than a private individual owning an image of my grandmother. The book has the full context. I do sell images that are landscapes or devoid of people, but things with my family or children are not for sale. I can see the work being collected by a museum or another archive that will speak to the people, the place, and the time.

What I hope people get from the work is a genuine and honest expression of a Black experience in the rural south that is contemporary. What are we interested in and what do we care about? So many Black people have told me that they see themselves in my work, and that is truly the biggest honor. The ability for my work to create community and dialogue outside the traditionally tragic images of Black people is important to me. It feels like I am aiding in achieving a balance when it comes to Black representation. This is why I focus on the landscape, to force viewers to witness Blackness outside of our bodies; beyond our skin.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Learn more about Jamie Robertson here.

Current exhibitions include: A Hundred More at the Galveston Arts Center, which ran August 27 – November 13, 2022; Love Is A House That Even Death Can’t Knock Down at Lawndale Art Center, which runs through December 10, 2022; Lo que me queda de tu amor (What’s left of your love for me) at Lawndale Art Center, which runs through December 10, 2022; and Black Love Now at Nicole Longnecker Gallery, which runs through December 31, 2022.