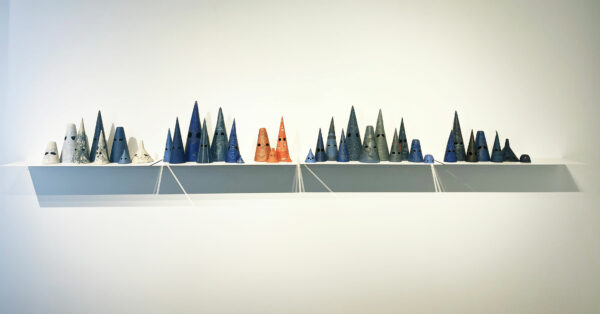

Tammie Rubin, “I Pick Up My Life” (installation view) at Galleri Urbane, Dallas. Photo by Colette Copeland.

Through a variety of media and processes, Tammie Rubin’s inaugural exhibition at Galleri Urbane in Dallas explores personal, ancestral, and collective experiences of Black Americans throughout history. Using coded symbols and mapping on sculptural forms and in drawings and installations, the work speaks to the exodus of Black Americans from the south to the north.

The visually arresting conical porcelain sculptures from the Always & Forever series look like ceramic KKK hoods. Upon closer examination, Rubin employs a variety of structures besides the hood, including dunce caps, inverted traffic cones, funnels, and snow cones. Historically, the conical hood did not represent violence and terror; a gold conical hat dates back to the Bronze Age, and in Spain during Semana Santa (Holy Week), religious penitents don white conical hoods to symbolize their dedication to penance. These forms are also present in Mardi Gras pageantry and African headdresses.

Rubin’s sculptures evoke a conflation of emotions from shock to awe. The eye holes anthropomorphize the sculptures, as do their arrangement on the shelves. They are grouped together like small families, staring mutely and expectantly at viewers. By using multiple types of conical forms, Rubin asks her viewers to expand their perceptions of the symbolism inherent in each: traffic cones signify both warning and safety; funnels connote domesticity for me, but perhaps science for others. And snow cones — references to hot summer days of childhood.

Each sculpture has detailed painted patterns and textures that require multiple firings in the kiln. Some patterns reference constellations, as well as maps of the migration journeys of Black Americans. A few sculptures also have police badges embossed on their surface. They’re very subtle, and I doubt I would have noticed had I not been studying the works intently while speaking to the gallery director. Juxtaposing a symbol so closely tied with police violence against Black Americans strikes me as a defiant, yet courageous act — one that references history, but perhaps also is a gesture of hope and unity for the future.

Another series includes collaged prayer fans hung on a painted mural entitled Monkey Wrench, North Star, Flying Geese. The three yellow symbols in the mural refer to quilt patterns used by the underground railroad to aid enslaved Americans in their flight to freedom. Rubin collages family photographs and flower patterns onto the masonite prayer fans, which works well to invoke memory. Historically a utilitarian staple in black churches, the prayer fan symbolizes family, community, and resilience. Against the brightly colored mural, the fans serve as a family photo album of sorts, but also a legacy, an archive that remains visible and on display.

Behind the mural wall of the gallery is a hidden enclave with another installation entitled Breach, which consists of hundreds of red and white stake flags. Used to designate borders and boundaries, the flags serve as another type of map — one of both migration and establishing roots, as well as claiming space for oneself. The title, Breach, means to rupture or crack. The act of claiming land and space is a radical act for dismantling systems of racial oppression.

Tammie Rubin, “Breach,” 2022. Photo by Colette Copeland.

The last gallery wall has three 11 x 14-inch plotted pen and ink drawings. These are easily overshadowed by the other work in the exhibition, but worth close examination. The delicate markings feature contour line drawings of a couple with overlaid plotted plots referencing maps and journeys. The work serves to remind us of the interconnectedness of communities and their influence over our lives.

The exhibit’s title — I Pick Up My Life — at first seems a curious choice, as if it refers to a life interrupted or on pause. When I discovered that the phrase also means to claim, it made immediate sense. The phrase comes from Langston Hughes’ poem, “One Way Ticket“:

I pick up my life

And take it with me

And I put it down in

Chicago, Detroit,

Buffalo, Scranton,

Any place that is North and East,

And not Dixie.

Rubin’s work claims her family history, claims the migration of Black Americans, and also reclaims important historical symbols. The artistic act of mark making serves as a definitive act of reclaiming power.

I Pick Up My Life is on view at Galleri Urbane in Dallas through November 12, 2022.

2 comments

Colette, Thanks for writing about Tammie Rubin’s show. I was glad to see some of Rubin’s related artworks a little while ago at HCCC.

Brian,

There’s so much detail on the sculptures that require in-person viewing. Glad you could see her work at HCCC.