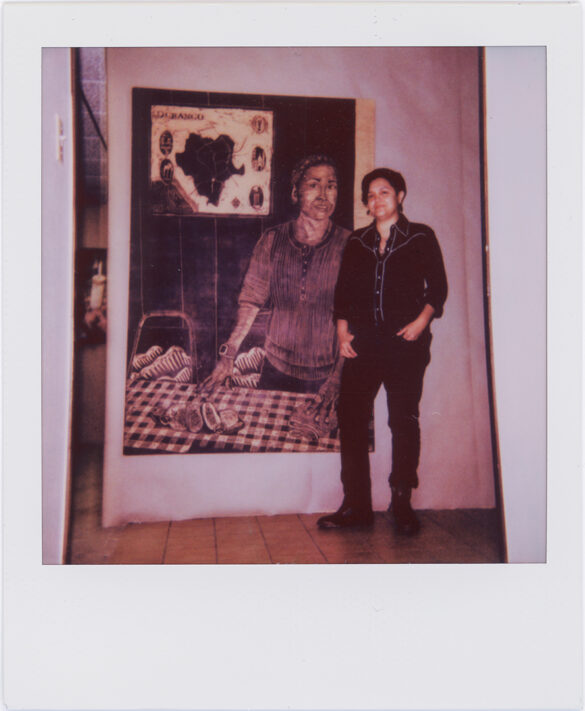

The DIY art scene offers a unique opportunity for emerging artists to come together and experiment. For those who have been historically underrepresented and underserved in the arts, these spaces are also a vital way to foster community outside of longstanding institutional power structures. Last year, Jose Villanueva, architect, artist, curator, and self-proclaimed “forever student,” opened his home as a venue to host one-night art events featuring artists of color. Villanueva calls his space El Refugio, which can be translated as the refuge, after his hometown in Mexico.

What prompts an engineering student to open his home to fellow creatives? Villanueva was inspired by the profusion of artists whose work he sees online but not in local galleries. He thought that if he found a way to show the work, that the artists would be willing to exhibit it and the public would want to see it. As he tells it, “The pandemic had me refocus my energy on things that bring joy, this came out of that.”

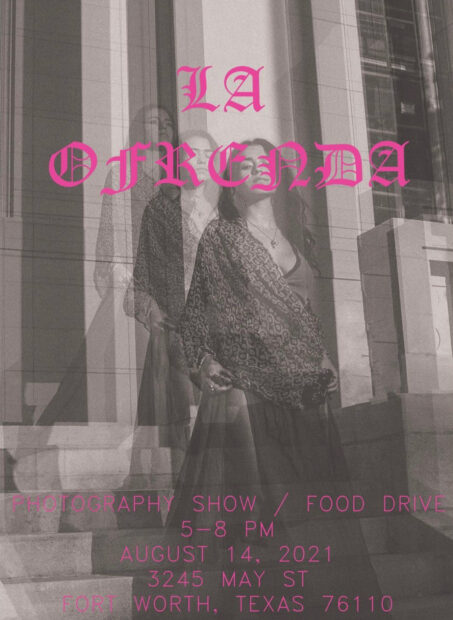

In August 2021, Villanueva’s first exhibition, La Ofrenda (The Offering), featured photographers Hope Mora, Raul Rodriguez, Sonny Martinez, Tony Krash, Gabi Magaly, E. Johnson IV, Melissa Gamez-Herrera, Melissa Cunningham, Moraima Villela, Erika Nina Suarez, Itzel Alejandra, Miguel Angel Salgado, and Martha Rincon. For the announcement of this inaugural show, Villanueva, who also dabbles in poetry, wrote: “in honor of the world we are creating. A world we have control of: molding and re-shaping to better fit the needs of the land and its children. This is an offering; to a new world. Esta es una ofrenda; a un mundo nuevo.”

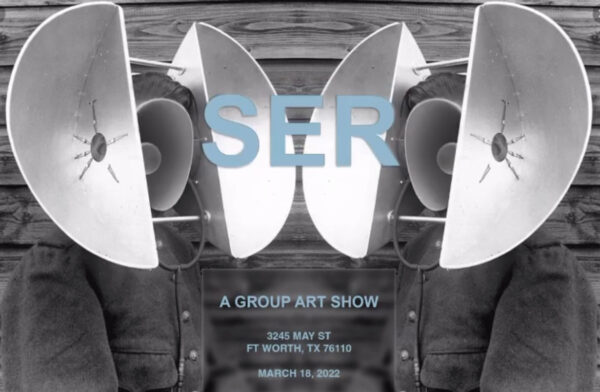

Though supporting the visual arts was the original focus of the space, Villanueva is also finding ways to incorporate performing arts. The first show featured performance artist Auris Solaris and the second exhibition, in March 2022, saw the inclusion of musicians. This exhibition, titled Ser (Being), featured works by Fabian Guerrero, Tony Krash, Steven Gonzalez, and Enrique Nevarez and music by Pintalabios (Karmina), Ynfynyt Scroll (Putivuelta) and TAYHANA (Naafi).

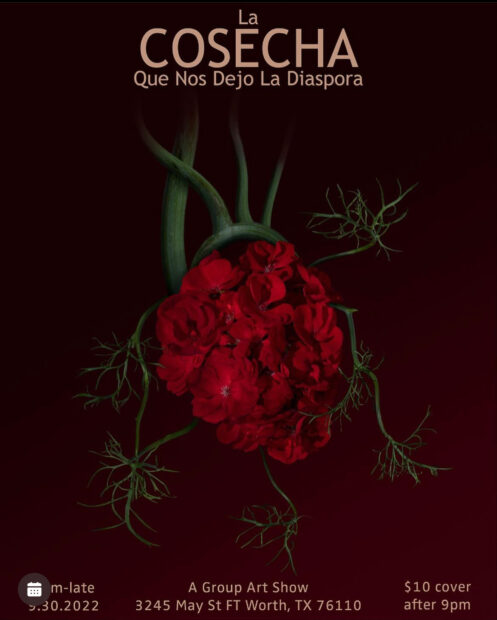

Villanueva’s recent exhibition, La Cosecha Que Nos Dejó La Diáspora (The Harvest that the Diaspora Left Us), included music by Nudo, Pintalabios, and Vacio Sur, as well as art by Christopher Nájera Estrada, Troy Ezequiel, Ángel Faz, Agustín González, Michelle Cortez Gonzales, and Alejandro Macias. The show was also originally going to feature a performance by Dallas-based art educator Roy Martinez, for which he planned to grind an American flag on a metate; this ultimately didn’t happen, due to a scheduling conflict. This exhibition, featuring Latine artists exploring their personal connections to Mexico, brings together artists working in a variety of mediums who are deeply influenced by their culture.

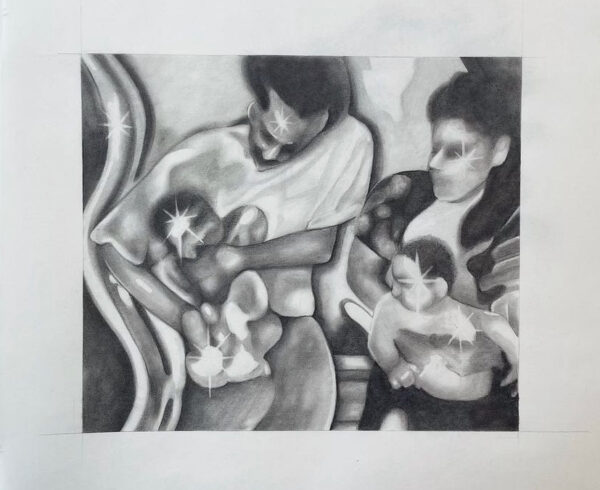

Fort Worth-based mixed media artist Christopher Nájera Estrada often incorporates drawing, text, and Baker-Miller Pink, a particular color often used in hospitals, in his work to scrutinize gender roles and mental health stigmas in relation to Chicanx culture. Most of the small-scale pieces on view at El Refugio were pencil drawings of slightly distorted images of young families, with the appearance of a glare or shine on each figure. The series, como brillan los ojos (how eyes shine), incorporates the shine effect Nájera often uses with his text, transforming a common family scene to a surreal moment.

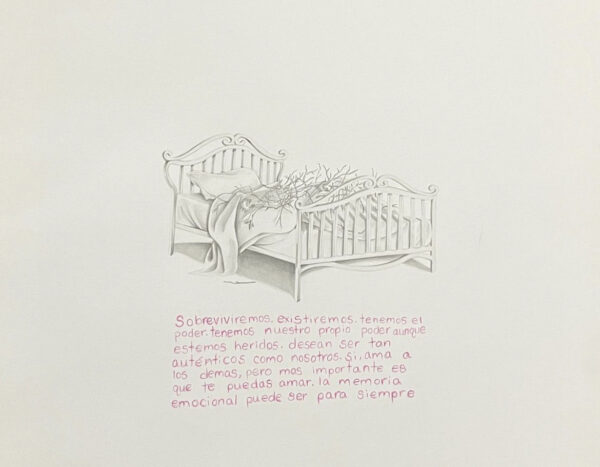

Another new work, destendida (unmade), incorporates a more realistic drawing and pink text, but overall feels quite different from the artist’s typical style. Whereas the text he uses is often short phrases, like “estas listo” (are you ready) or “lo que se ve, no se pregunta” (one does not ask what one can see), rendered in three-dimensional drippy fonts, the text in this piece is pink, in a simple handwritten font, and consists of several lines that read like a poem. The content of the text is like a mantra or declaration: “we will survive. we exist… we have our own power…”

On the surface, the imagery in the drawing itself — twigs or wilted flowers piled on top of an unmade bed — is a departure from Nájera’s usual references to low riders, Catholic iconography, and families. But looking closer, the work alludes to self-care and recovery, perhaps beyond the individual and reaching across generations. Both the bed and the natural items can be viewed as references to labor — like housekeeping and land maintenance, respectively — which are typically associated with immigrants, particularly Latino workers. What initially comes across as a depressing image is transformed by the inclusion of the uplifting text.

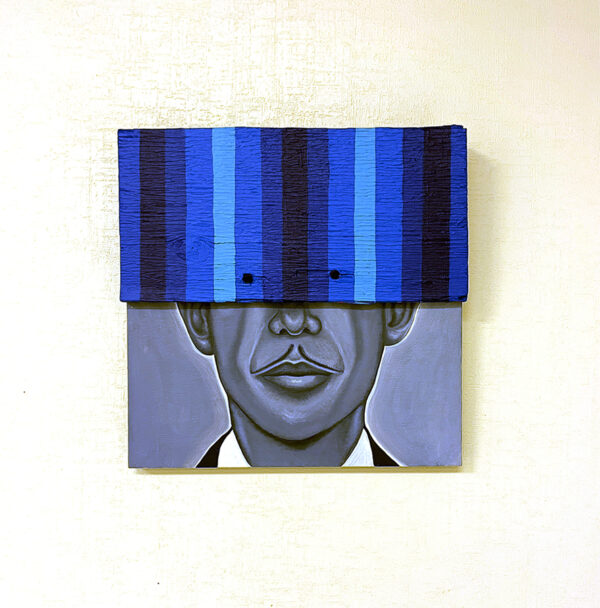

Brownsville-native and Tucson-based Alejandro Macias had two small works on view that are black and white portraits of his grandparents. Each painting is partially covered by a layer of wood, painted with shades of blue. While Macias’ earlier works incorporate a similar juxtaposition of figures and bands of color, these new pieces move beyond painting to become slightly sculptural. These should, perhaps, be considered works-in-progress, as they are not yet what Macias originally intended.

The small circles cut from the top layer of the work were originally meant to frame a video depicting a flowing river. Both portraits use variations of the title Like Tears in the Rain, a reference to a Blade Runner quote: “All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” The artist is commenting on how, through assimilation across the generations, his connection to his Mexican roots will eventually disappear.

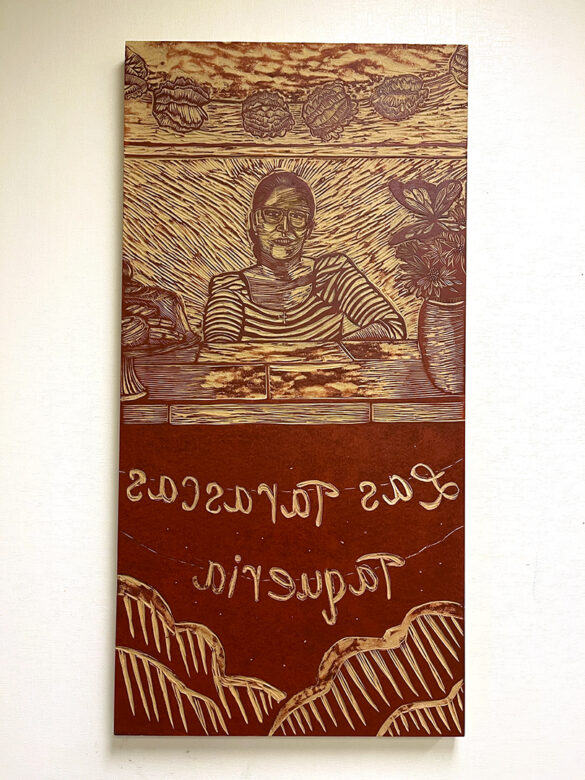

Other works in the show illustrate the shared experiences inherent to immigrant stories. Faz’s wood carvings from their series Dreamers, highlights local entrepreneurs who are bringing their dreams to reality through hard work and determination. (Full disclosure: some of the works on view at El Refugio had been originally created for an exhibition at Kinfolk House, where I serve as the Executive Director.) Cortez Gonzales’ mixed-media works, which incorporate fabric and blend imagery in a style reminiscent of magical realism, come across as memories of loved ones across generations and space.

Ezequiel’s subtle photographs depicting everyday, tender moments of family members in his hometown of Zacatecas are filled with longing and speak to the realities of separation. González’s photos, by contrast, are more dramatic and give viewers a glimpse of an array of celebrations centering la Santa Muerte, which took place in New York earlier this year. While place is inherently important to the understanding of Ezequiel’s work, the locations of his and González’s scenes are obscured, as there are no clear identifiers of place.

La Cosecha Que Nos Dejo La Diaspora brought together Texas-based Latine artists to show work and build community in a relaxed setting. Unlike many galleries and museums, Villanueva’s space is intentionally inviting — he realizes that an art show alone isn’t the most welcoming environment, so he uses music to draw visitors in and make them stay awhile. Though there are just a few exhibitions a year and they are each one-night events, El Refugio holds much potential to foster community among artists of color in and beyond the DFW area.