A photo from Bruce Yonemoto’s series “NSEW,” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

In the era of social media, speaking critically or living authentically can feel so attainable that overlooking our past, or neglecting present-day threats to our freedoms and liberties, is beguilingly easy. It wasn’t that long ago in 1955 that singer/songwriters Pete Seeger and Lee Hays were called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in an attempt to unmask their communist ties during the Red Scare of McCarthyism. They were essentially called by Congress to publicly defend their right to free speech. FotoFest’s 2022 Biennial, titled after Seeger and Hays’s protest song If I Had a Hammer, calls on us to consider the hammers that we wield and how we can use our power to critically question the historical and contemporary structures that influence ideological formation. How can we resist singular hegemonic ideologies and forms of representation?

Establishing a historical context for the exhibition, Dorothea Lange and Toyo Miyatake bookend the Silver Street galleries at the east and west ends of FotoFest’s main headquarters. Their photographs reveal two divergent perspectives in documenting the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Lange, a seasoned documentary photographer known for her Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs, worked on assignment for the U.S. War Relocation Authority (WRA), a government agency established to handle Japanese Internment. Toyo Miyatake owned a photo studio and gallery in Los Angeles prior to the U.S.’ entry into World War II. Miyatake was incarcerated, along with his wife and four children, in Manzanar, one of ten “relocation center” concentration camps. While Lange was hired to take photos by the U.S. government, Miyatake had to sneak in camera parts and surreptitiously take photographs, since cameras were banned in the camp. He eventually was discovered, but gained permission to continue photographing with restrictive stipulations. Juxtaposing these two perspectives invites inquiries into what is gained or lost by the access allotted or limitations imposed on Lange and Miyatake as they document the same grievous moment in U.S. history.

Lange and Myatake’s photographs establish a theme of critical engagement with history and representation that runs throughout FotoFest’s central exhibition. Bruce Yonemoto’s three projects epitomize these interconnected themes by reinterpreting Western imagery and cinema through an autoethnographic lens to address Asian-American representation. Raised by a mother who was one of 120,000 Japanese-Americans incarcerated during the U.S. Japanese internment, and a father who was drafted into the U.S. Army, Yonemoto grew up fascinated by movies and television. When researching Civil War archives for his NSEW project on view in Silver Street, Yonemoto was disappointed by the lack of Asian American cartes-de-visite portraits of Civil War soldiers, despite their participation in both the Northern and Southern armies. Utilizing Union and Confederate uniforms from Western Costume, Hollywood’s oldest collection house, Yonemoto created contemporary carte-de-visite-inspired portraits of Asian male models as stand-in soldiers. Some of the costumes used came from D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film Birth of a Nation, a cinematic classic known for its brazen racism.

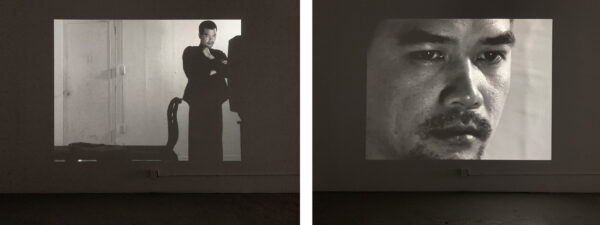

Installation view (long and close-up shots) of Bruce Yonemoto’s “Before I Close My Eyes,” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

Another series of photographs by Yonemoto is on view at Winter Street Studios, along with a video titled Before I Close My Eyes. This video reimagines a scene in Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 psychological drama Persona. In the clip, screen actress Elisabet Vogler suffers a mental breakdown in her hospital room after watching a newsreel that depicts the 1963 protest and self-immolation of Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk Hòa thượng Thích Quảng Đức.

The artist closely mimics the original scene structure, but replaces the actress with three Vietnamese men wearing Vietnam War-era uniforms who watch the footage in real time. Yonemoto mimics the classic Hollywood narrative film structure that Bergman uses in the scene — a cycle of long, medium, and close-up shots developed by D.W. Griffith in order to create intimate character identification. Yonemoto’s video switches back and forth between the men’s reactions and the actual footage, forcing the viewer to digest the shocking scene along with them. A nearby vitrine holds a small archive of vintage photographs depicting Vietnamese soldiers, which were taken from 1959-1974, during the American War (as it is known in Vietnam). This juxtaposition of archive and lens-based media connects contemporary concepts back to real people and histories.

Installation view of Ryan Patrick Krueger’s “Yearbooks and Dear David (Semiotics #2),” and close-up view of “Dear David (Semiotics #2),” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

Yonemoto is not the only artist in the biennial to utilize personally collected archives. Ryan Patrick Krueger’s Dear David (Semiotics #2), an homage to and extension of David Deitcher’s book Dear Friends: American Photographs of Men Together, 1840-1918, uses found photography to underscore the complicated history of gay culture prior to the Stonewall riots in 1969. Krueger collected photographs on eBay that were made between 1919 and 1969: images such as a man’s hand on another man’s shoulder, or photo booth images of men’s cheeks pressed together. Could they be photographs of friendship, or of a concealed romance?

Krueger’s artwork represents an era shaped by the Lavender Scare, which was similar to the Red Scare during McCarthyism. Being gay meant losing your job, your family, your friends, and potentially your life. How firm of a history can you build as a culture when sharing your authentic self could end your life?

Instead, viewers must reflect on photos and ephemera with a sharp eye, deciphering larger signs out of subtleties. Krueger’s photos are layered with shipping materials and printed eBay listings in a pine box steadied on a mound of black sand. Inspired by Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s piles of candy, the sand stands in for a body’s worth of ashes precariously holding up this unstable history. Two large multi-photo adhesive pigment pieces emphasize the sense of loss and searching in these photos, with tapered candle wall sconces that insinuate mourning, for lost love and a lost history.

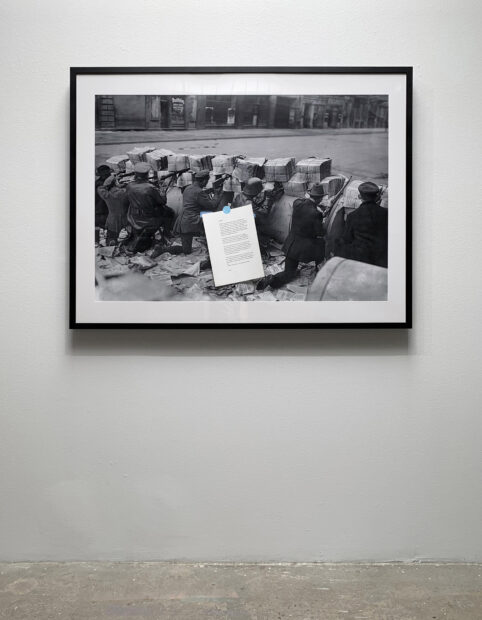

A photo from Ines Schaber’s “Culture is Our Business,” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

In Culture is Our Business, Ines Schaber also responds to themes of lost history, particularly in the context of image archives. In it, she reprinted a copy of Willy Römer’s Street Battles in Berlin from 1919. The image depicts civilian revolutionaries and professional military fighters taking cover behind bundles of newspapers in anticipation of approaching governmental soldiers. However, in Schaber’s research, she discovered that despite coming into the public domain in 1929, the image was accessioned by Bill Gate’s Corbis archive (a digital stock photography company), where a new caption accompanying the photo misidentified the combatants as members of the German government forces. Corbis perpetuated a false narrative that continues to circulate in books, online, and through institutions and archives. This one image demonstrates the potential fallibility in resources of information, further reminding us that history is malleable and can never fully represent the past.

A photo from Reynier Leyva Novo’s series “Un Día Feliz [A Happy Day],” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

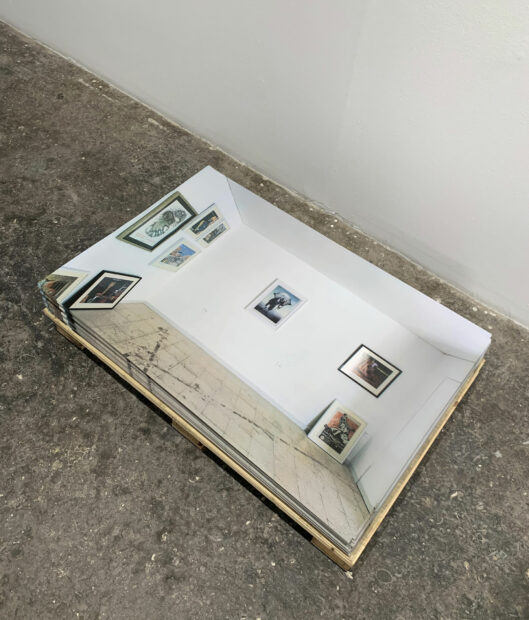

Installation view of Yazan Khalili’s “Copy of a Copy of a Copy,” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

Diverging from themes of lost or distorted history, representation and identity is a reclaiming of what is lost. Yazan Khalili’s Copy of a Copy of a Copy expands on the history of Palestinian artist Suleiman Mansour’s 1973 painting Jamal Al Mahamel II [The Camel/Carrier of Hardships II]. The painting depicts an elderly Palestinian man carrying the city of Jerusalem, contained within the shape of an eye, on his back. The painting was made into a poster in 1975 and quickly became a popular symbol of resistance and regional identity, hanging in nearly every home throughout Palestine and beyond. The original painting was destroyed in 1986 by the U.S. bombing of then-Libyan dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi’s residence. The artist repainted it in 2005. At this point, there is no original, just copies. Mansour’s image is more of a symbol than an object, one that any person can own. In the show, Khalili offers take away posters of a photo he made of a copy of this painting on display in a gallery. Anyone can bring a poster home and further disseminate the image and its symbolic history.

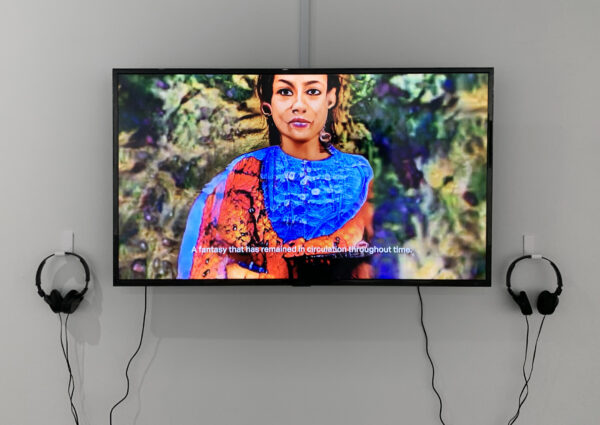

Installation view of Mónica Alcázar-Duarte’s “I am not data his Monster Exists,” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

Mónica Alcázar-Duarte reclaims identity by examining the role of complex invisible search engine algorithms in perpetuating misrepresentation, stereotypes, and bias. The artist’s Second Nature portraits combine information from over 100 interviews with Mexican women with data from web searches. They reveal harmful stereotypes that minimize the diverse individuality of Mexican women.

In two portraits, Alcázar-Duarte employs augmented reality through Artivive, a user-friendly app that viewers can download to see interactive animations and music that compliment the portraits. Her code-generated video I am not data his Monster Exists expresses her message in a strikingly poetic manner: Alcázar-Duarte collected portraits of Mexican women from a crowdsourcing database and worked with creative technologist Bente de Bruin to create a GAN-generated video that morphs each portrait into another in an abstracted homogenized way that, when combined with the video’s subtitles, is a defiant message against typifying people based on race or gender.

Installation view of Jonathan David Smyth’s “Between You and Me,” on view at Silver Street Studios as part of “If I Had a Hammer.” Photo: Britt Thomas

A number of artists in If I Had a Hammer reclaim representation through self-portraiture and connect with the land in order to counter accepted Western ideals. Located near Alcázar-Duarte’s works are Laura Aguilar’s black and white nude portraits of herself and other models in the Mojave Desert from the 1990s. They challenge standard Eurocentric depictions of beauty, and bring attention to marginalized communities.

Across from Aguilar’s photographs is a tight eye-level line of nude self-portraits made during the pandemic lockdown by Jonathan David Smyth. Smyth’s statement about his work mentions how the body is a source of cultural identity that becomes a source for meaning to be extracted and expressed. Similar to Aguilar and Smyth, other artists in the exhibition, such as Lorraine O’Grady and Keisha Scarville, explore representation and identity through the body and landscape. O’Grady’s video Landscape (Western Hemisphere) features intimate close-up video footage of her natural curls fluttering between two fans that are out of frame. Paired with a soothing score of ambient natural sounds, it is easy to lose oneself in O’Grady’s dimly lit curls, which begin to transform into a nightscape of cattails swaying in the wind to the sound of crickets chirping.

While it is extremely tough to curate a cohesive group exhibition of this scale, curators Steven Evans, Max Fields, and Amy Sadao (with curatorial advisory support from Julie Ault, Nora N. Khan, and Jeanne Vaccaro) have created an engaging discourse between very disparate approaches to addressing a complex theme.

If I Had a Hammer also includes the art of Chow and Lin, Forensic Architecture, Elaine W. Ho, Ho Rui An, Jibade-Khalil Huffman, David Kelley, Dionne Lee, Delilah Montoya, Mike Osborne, Liz Rodda, and Fred Schmidt-Arenales in collaboration with David Ramírez Cotón, Daniel Hernández-Salazar, Camilla Juárez, and Jorge de León. The exhibition is on view at Silver Street and Winter Street Studios through November 6, 2022. Visit FotoFest’s website for more information on their other exhibitions, Biennial programming, and FotoFest participating spaces.