This past summer, when I visited the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska, I was sure to connect with artists living and working in the area. I see exhibitions across Texas year-round, and I find it refreshing to take similar exhibition tours and make studio visits outside of the Lone Star State. As you’ll read, no matter where art is being shown, or where artists are living and working, there are always exciting commonalities to be found, or surprising differences to be explored. Below, I recap my visits with few artists, and discuss what I learned about their practice.

Casey Callahan

Casey Callahan’s Breeze and Bloom is an installation inside a shipping container. For our visit in August, it was sitting at the intersection of Elm Street and Vinton Street. Previously, it sat at 1231 Park Wild Avenue. The venue is CAR>GO (Community Activated Resource on the GO), a shipping container gallery operated by Holly Kranker and John Cohorst, and funded by the Amplify Arts 2019-2020 Public Impact Grant, a $10,000 grant for Omaha artists and organizations producing programming for local communities. The two doors at the front of the installation were flung open, and a soft glow welcomed us inside. Callahan was offered the opportunity to exhibit July 15 through August 23 of this year, and so she began asking herself, “What can I make that works with this architecture that is true to me?” Finally, she came upon her answer: “It’s all about wind and breeze.”

Black and white sheets of paper line the interior walls of the container, and natural elements are affixed throughout the space. Callahan has been exploring mobiles made of raw twigs and beaded strands weighed down by metal baubles. A rod sticks up from the ground, daubed with putty and then stuck with colored fiber filaments, which droop with a Seussian silliness.

Callahan’s response to the space has been to mute the environment with basic principles (a checkered pasteboard, à la photoshop) and then place objects that catch light in interesting ways. A mesh rainbow curtain separates the majority of the interior space from a rear anteroom, where the viewer can watch the sun set. The dynamism of light and opacity makes the space feel like a dream.

****

Caitlin Cass

Caitlin Cass is an American comic artist who is originally from the Chicago area. She lived in Buffalo, New York for 11 years, where she earned her MFA in visual studies from the University at Buffalo, SUNY. She relocated to Omaha specifically to teach at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and has developed four classes for an illustration concentration in the studio art program.

Comic artists and illustrators are one of many types of artists working in a technical craft which lends itself endlessly to creative production. However, it still takes time. Each page takes 5 hours to ink, and 3 hours to color. One wall in her home studio is covered in pages arranged in preparation for her next publication project, which made it seem, to me, that between drawing, writing, and coloring an entire book, there must be an endless amount of planning involved. I was astonished to discover that Cass works one page at a time, writing the whole thing as she goes. I asked what led her to a nonfiction comic practice on the topic of American history, and she told me, “I’ve read a lot of history comics that lack poetry. I’m trying to do something that’s not just educational. I’m trying to build folk tales out of actual history.”

****

Shawnequa Linder

Omaha artist Shawnequa Linder and I share something in common: we began as graphic design majors in school, but soon were drawn to the traditional studio arts. “I was very interested in being a photographer, but I didn’t know what kind of photographer I wanted to be,” she tells me at her home studio near the University of Nebraska Omaha.

Linder describes herself as a “late bloomer,” meaning that her art practice came to be through a lineage that is not direct. Her first forays into photography were experimental, and she soon discovered her interest in exploring and documenting texture. Those experiments have spun off into another pursuit: painting. Sifting through photography slides and stacks of canvases in her home, Linder reflects on making art and learning about it at the same time:

“I’ve been on this journey. I call it my art journey. I’ve been on it ever since I finished school. I told myself I had a list of things that I wanted to accomplish.”

When asked about her experience exhibiting, she says she has participated in a lot of group shows at local spaces like Project Project, Split Gallery and Radial Arts Center. They’re great places to show work, and her participation also reflects her kinship with the art community in Omaha.

“I have a lot of support, which is good on this journey I’ve been on. I’m just looking forward to seeing what else I’m gonna get myself into.”

****

Nick Miller

Nick Miller, who teaches sculpture at the University of Nebraska Omaha, says that he knows how powerful a bold color can be. “I’ve primed a building a base coat color, and had neighbors come over and be horrified because it got painted all pink,” Miller tells me, in his Benson neighborhood studio. “I’ve watched color, the quick change of color to somebody’s environment completely affect them in a way that makes them feel uncomfortable; they’re not sure what’s happening.”

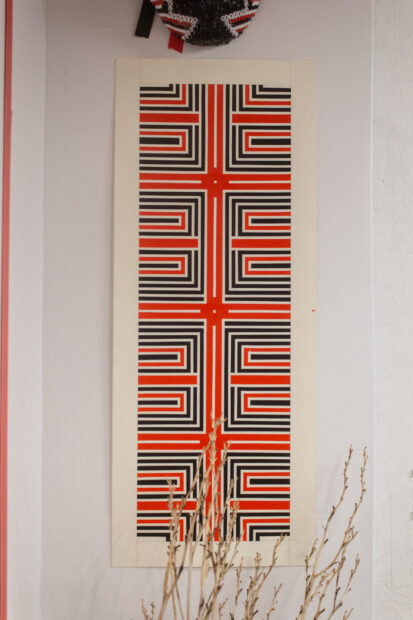

Miller speaks from experience, given that his work is frequently installed in large interior spaces, or as a mural that wraps around a building. His lines are hard and right-angled. Paint is applied to exterior walls in the instance of a mural, but when he is installing indoors, colored tape is his medium. In 2020, he showed the tape installation Zebra with a Sunburn at Project Project, a DIY art venue in South Omaha which shows new exhibitions on the second Friday of every month. The interior of the long corridor-like gallery was covered in tightly alternating lines of red, black and white tape. The result was a glowing circuit pattern that covered all walls and floors and shook up the senses. I asked him how the work came to be:

“I’ll design at home and do it on paper or panel. But the majority of my work for six years was all exterior murals that I did in different places on different kinds of structures.”

A wooden maquette of a rectangular structure with an open center sits in his studio, painted in cool blue and pinstriped in yellow. The dedication to strict line and color is an approach not unlike that of Sean Scully, a painter’s painter. What makes Miller’s work interesting is the multiplicity of his approach to scale and architecture. Miller’s response to painting is often semi-permanent; tape inevitably is removed from the walls and murals are sometimes painted over. Even so, Miller’s work is arresting.

****

William Anderson

William Anderson had just moved into his new Leavenworth Street studio, down the street from the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, when we toured the space in mid-August. In recent weeks, he had been liquidating his old studio and putting its contents up for grabs online. He told me, “I was on Instagram, calling it a fire sale, moving sale. The old inventory. Some of it was very old. It worked!” The result is that his new space isn’t jammed with too much stuff. Accordingly, Anderson bounced with the excitement of a new tenant while we looked at his recent work.

What is the new work? Similarly pared down like his studio, the work has become equally clarified. Canvases, 80 x 70 inches, are primed with white and feature 100 sunglasses in untidy rows. They look as if they have been set down and the table they’re sitting upon has been shaken slightly. When asked about his use of spectacles in his work, the artist told me, “Black sunglasses are like the blackest substance I can think of.” At this scale, there is a quiet importance of the image of so many plastic, fragile objects. Anderson tells me these paintings are akin to that sensation, or “Feeling the energy of something very small 100 times. Serial nature is something I’m leaning into.”

Anderson is, by all accounts, from Omaha. “Elementary through high school, you know,” he says to me. After a BFA in painting from the Kansas City Art Institute, he returned to Omaha and has remained ever since. He has experience installing exhibitions at Bemis, alongside Nick Miller. Seeing an artist with an extended relationship to place made me wonder where his work has found its home. He offered one anecdote of a sale of his work at the Bemis auction, an annual art sale and fundraiser of local work akin to Blue Star Contemporary’s Red Dot Auction. A story emerged from the sale of the piece, a small painting featuring a series of black eyeglasses: “I found out later from people visiting this office, it actually went to an optometrist’s office, which amused me.” Anderson felt the need to find the owner and talk about the work’s relationship to its new home. “We had a nice little chat,” Anderson recounts to me, “I was just like, you gotta understand that this is so funny to me. It was so far from what I’m thinking when I make these.”