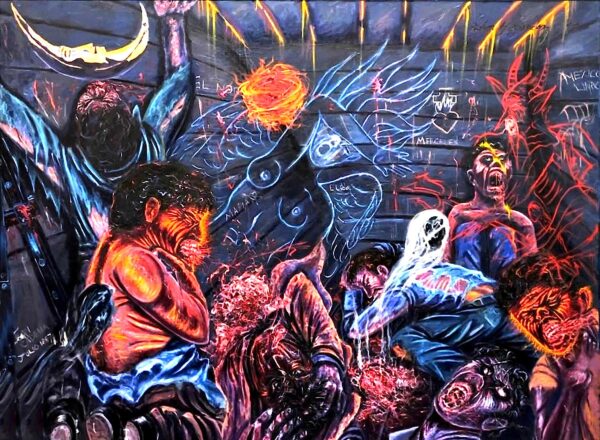

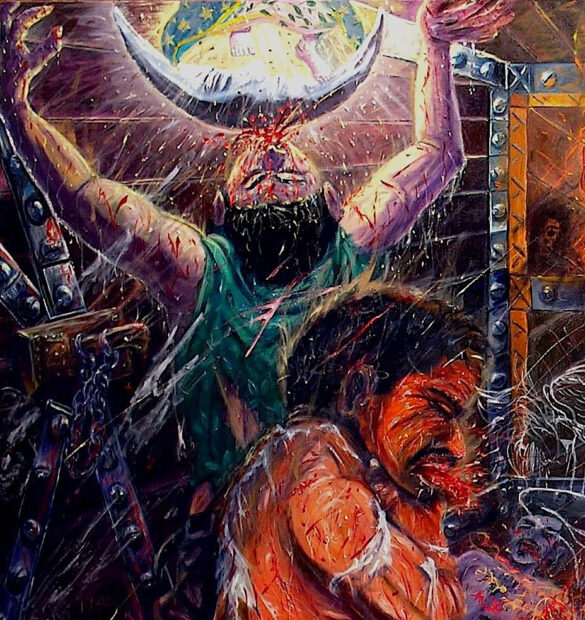

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of angel and devil fighting for a departing soul), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela. All photographs of this painting in this article are from a cell phone picture provided by the owners.

In June of 2022, 53 migrants perished under hellish circumstances after traveling in an unventilated semi-truck trailer that was abandoned in San Antonio, Texas. There have been many such attempts at dangerous and surreptitious migration, but they only come to general attention when death tolls make them “newsworthy.” Lomi Kriel and Uriel J. Garcia discuss several of these desperate attempts in their article “Death is a constant risk for undocumented migrants entering Texas” (Texas Tribune, June 28, 2022).

Between fiscal years 1998 and 2020, the U.S. Border Patrol estimated that 8,000 migrants died in the Southwestern U.S. border region. The Border Patrol listed the 2020 death toll at 247. Priscilla Alvarez reported in CNN that the Border Patrol estimated 557 border deaths in 2021, while the International Organization for Migration (IOM) put that number at 650, the highest total since it began documenting these deaths in 2014. Michele Klein Solomon, an IOM regional director, called this death spike “highly alarming.”

This article analyzes two paintings by Adan Hernandez. They are alternate versions of Diez y ocho illegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar, dated 1993 and 2010, respectively. These harrowing paintings are responses to the excruciating deaths of 18 immigrants in a railroad boxcar near El Paso, Texas in 1987. For an introduction to Hernandez, see my Glasstire article: “Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night, Part 1: The Birth of Chicano Noir” (hereafter referenced as Hernandez, Part 1).

In the second part of this article, I examine: the historical causes of immigration to the U.S. from other countries in the Americas; specific U.S. policies that are resulting in greater suffering and more numerous migrant worker fatalities; and contributions made to the U.S. economy by unauthorized migrant workers.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (slightly cropped on the sides), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

I included the 1993 version of Hernandez’s Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar in an exhibition I curated at the Centro Aztlán in San Antonio in 2004, for which I wrote the following text:

Adan Hernandez addresses immigration policies and class disparities in two paintings. Diez y ocho illegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar (1993) is an uncompromising response to a news-story about eighteen immigrants who suffocated in an unventilated boxcar. Hernandez’s painting is a nocturnal Masque of Death: The victims’ faces are contorted into desperate grimaces as they make their final gasps for air. While they expire, a ghostly angel and devil battle for their souls. Even the angel appears to be gasping for breath. She raises her arm in a protective gesture against a fireball that swirls in her direction. On her left, a ghostly skeletal face belonging to a departing soul emanates from the detritus of a victim’s exploded corpse. This hot, oxygen-deprived environment is clearly one in which the devil has the advantage. While the angel recoils, the devil reaches for his prize.

I offer a fuller analysis of Hernandez’s paintings below, after a discussion of the incident.

Death by Railroad Boxcar, 1987

Nineteen men boarded a Missouri Pacific boxcar in the El Paso freight yard — only about a mile from the Mexican border — around 5 pm on June 30, 1987. Fourteen hours later, only one of them would emerge alive. Two of the men in the boxcar were smugglers (known as coyotes). An additional coyote, who was nicknamed el Chapulin (the grasshopper) locked them inside the car. This was done to avoid inspection. The New York Times reported that 52 undocumented migrants were captured by the Border Patrol on this very train before it departed. Since the locked boxcar was assumed to be empty, no one checked it in El Paso.

The train was bound for Dallas-Fort Worth, which is a common destination for migrant workers. Undocumented immigrants hide when they are already within the United States until they are far from the border in order to avoid checkpoints and the Border Patrol. This is a consequence of the militarized border discussed below. The Border Patrol routinely conducts warrantless searches within 100 miles of the border. (Check this ACLU link to know your rights.)

The boxcar was opened during a routine inspection at 7:28 am on July 1, about 85 miles east of El Paso. A nightmarish scene was revealed that the Washington Post called “a dark little hell.” Eighteen men were dead.

A Border Patrol spokesperson said asphyxiation was the cause of death. He told the Washington Post: “It was a horrendous sight. Many of them had heat convulsions, and they ripped off their clothes in desperation. There was a lot of blood inside the car.” The New York Times reported that, according to another Border Patrol spokesman, victims suffered “nasal bleeding in their mouths,” a sign that they had suffered convulsions.

The only survivor was Miguel Tostado Rodriquez, aged 21, from Pabellon de Arteaga in the state of Aguascalientes, Mexico. He was able to get sufficient oxygen by enlarging a hole in the floor of the boxcar with a spike. The two coyotes who subsequently died had begun the hole.

The New York Times gave this account on July 4, 1987 (Peter Applebome, “Boxcar Survivor Describes Ordeal“):

Two smugglers who had brought the Mexicans into the country illegally dropped first, said Miguel Tostado Rodriguez, the lone survivor. They had panicked in the heat and lack of oxygen and tried to dig their way out with a spike.

Mr. Rodriguez said the others in the rusty red car tore at their clothes and flailed at each other, then died in heat that probably exceeded 120 degrees. He lived, he said, by breathing through a 5-by-10 inch hole he and others had punched through the insulated wood floor of the darkened boxcar with the spike.

“I asked God to help me out,” said Mr. Rodriguez. “But I’m pretty sure the others did the same thing.”

The article relates that Rodriguez was the only person alive the last two hours of the trip and that the boxcar had an automatic lock. Rodriguez had been traveling between Mexico and the U.S. for four years. He had been captured by the Border Patrol the previous day, but returned again to board the fatal boxcar. Rodriguez planned to work as a waiter in a Mexican restaurant to support his wife and infant children. Among the objects left by the deceased immigrants was a notebook with a poem titled El Ilegal, which ends with a safe return to Mexico.

According to an Associated Press article, Rodriguez had recruited some of the men who joined him on the train. At least six of the deceased men were from his hometown.

The men had hidden in an insulated boxcar that was designed to carry beer. It retained the temperature it had when its door was closed (over 100 degrees). Due to the body heat of the men, the temperature inside the boxcar probably rose, with some estimates at 120 degrees or higher.

If the men had entered a conventional boxcar, they would very likely have survived their trip, since the temperature would have cooled considerably at night, and more air would have been available to them. The 1987 Washington Post article linked above noted that the Border Patrol found undocumented immigrants en route in trucks or boxcars once or twice a month in Southern Texas.

The Chicago Tribune quoted Debbie Nathan of LIBRE (League for Immigration and Border Rights Education) in the wake of the 1987 boxcar tragedy. LIBRE, according to Nathan, opposes “anti-immigrant hysteria.” She declared: “they [migrants] really have been reduced to the level of rats just to go to work.” The Tribune also noted that migrants hopping trains often suffer serious injuries, including lost limbs, and even decapitation.

Hernandez’s Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar, 1993

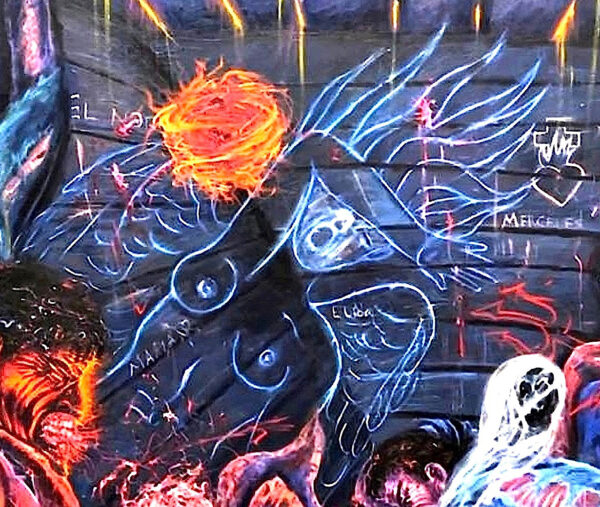

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (upper left section), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

I begin my discussion of this painting in the upper left corner.

The Virgin of Guadalupe is Mexico’s most popular religious image. It reflects imagery from the Immaculate Conception and the Apocalypse. Devotees believe it was miraculously created. (See this smarthistory link.)

The Virgin of Guadalupe stands on a crescent moon. In the upper left corner of Hernandez’s painting, she appears to have vacated that perch, though one could interpret the human face on that moon as a synthesis of human form and heavenly body. I think Hernandez utilized this form of the moon simply because he liked it.

Anthropomorphized moons of this sort are found in Mexican colonial and folkloric works that are derived from Spanish prototypes. Hernandez’s moon-woman is in a state of complacent sleep. In a reverse echo of the pose of the little angel that holds up the Virgin of Guadalupe, a man raises his arms. His pose, of course, is a reflection of his desperation. But the moon-woman is seemingly oblivious to his frenzied entreaties and prayers. The Virgin of Guadalupe has apparently departed from the moon. There is no salvation to be had in this boxcar.

Below this figure, the words “CADENA” (chain) and “JULIO 1987” are inscribed in the lower left-hand corner of the painting. Cadena must refer to the fact that the boxcar’s door has been locked, imprisoning the men inside. They are prisoners — as surely as if they were chained. Julio (July) of 1987 is when the men died and were discovered in the boxcar.

To the right of the man with the outstretched arms, “EL NORTE” (the North) is inscribed on one of the planks that line the boxcar (it is partially obscured by the fireball swirling just above the angel’s wing). One can see golden light streaming through the slats at the top of the boxcar. This utilization of wood paneling is an artistic liberty the artist has employed to create interesting effects. In reality, the boxcar had steel sides and a steel ceiling, which is why all but one of its nineteen passengers died on that fateful day.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of angel), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

Below the fireball, a transparent, screaming angel is rendered in crude outline, as if she herself were nothing more than a graffito, roughly carved into wood. She is depicted at a forty-five degree angle, cantilevered as if she were in the act of collapsing. One can see words carved into the boxcar slats right through her body. The name “MARIA” is a possible reference to the Virgin Mary (and to the prayer Ave Maria), though the fact that it is followed by a heart penetrated by an arrow makes it more likely to stand for romantic love for a girl named Maria.

In addition to graffiti on the wooden slat of the boxcar, the name Maria and the accompanying image could also read as a tattoo on the naked body of the angel. Hernandez is playing with the multiple meanings that this combination of words and images could potentially suggest.

The name Elica can be seen through the angel’s wing. As she holds her forearm across her forehead, the angel screams in anguish. Her triangular nose resembles that of a skull, expressing her extreme susceptibility to the heat. The angel has already lost her clothes. She does not appear to be capable of saving herself, much less the passengers in this boxcar of doom. The angel’s hair rises up like flames. Though the angel is blue, the color of the sky and thus of heaven, her hair conveys the sense of heat as powerfully as any other element in the painting.

One tip of the angel’s flame-like hair licks the corner of the flaming sacred heart that is surmounted by a cross. The name “MERCEDES” is inscribed under the heart, which stands for the Virgin of Mercedes (Mercy). It also invokes the luxury German automobile that serves as a symbol of the affluence that attracts immigrants from Latin America to the United States.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of devil), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

The devil is likewise painted in outline on the far right (which could be interpreted to mean that far right politics are demonic). As the artist Cesar Martinez notes, “nobody in our cultural milieu could paint a more expressly menacing, evil devil than Adan could.” He wields his pointed trident at the fainting angel. It nearly touches her outstretched hand. The devil’s dagger-like fingers almost prick the escaping soul, which vaguely resembles a Jivaro shrunken head. It is represented as a black head shrouded in streams of ghostly white.

While Hernandez was a devout Catholic as a child, he subsequently rebelled against authority, including religious authority. He became more interested in curanderas and popular cures and remedies than in official rites and dogma. Perhaps this is why he represented the soul in such an unconventional manner. Hernandez might also have intended to convey the idea that the soul was itself burned by the intense heat.

This black-faced soul rises from the steaming entrails in the lower center of the picture, which came from the man clutching his hands in the lower center, whose abdomen exploded. Hernandez dramatized the fatal convulsions that the men were suffering by having one culminate in a literal explosion. Moreover, artistically, it is a jab at abstract art: “abstract” forms are here transmuted into steaming entrails.

The words “MEXICO LINDO” (beautiful Mexico) are inscribed on one of the side planks, to the right of the devil’s head. On the other side of the devil, a man with his knees pulled up to his chest emits a horrific scream. It is as if he sees and feels the devil, whose long, forked tongue flickers above his head, no doubt presaging an imminent trip to hell. But could hell be much worse than this torturous tableau?

The simplified forms of the angel and the devil reflect their nature as primordial beings, imagined in an earlier period of human history. Without accepting the dogma of the church, Hernandez is always happy to deploy its symbols, especially devils (see my Hernandez, Part 1), crosses (I treat cruciform imagery in my forthcoming Hernandez, Part 2), and the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of angel and devil), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

The artist has taken the unusual step of gendering these conventional symbols of good and evil. The angel’s breasts are bared and revealed (though angels are supposed to be neuter).

Hernandez’s devil is a compendium of phallic attributes: note the horns, the pointed ears, nose, and beard, as well as his trident and fingers. For good measure, he also appears to have an erection. He is perhaps reaching for it with his right hand, which would equip him with a penis on one hand and a trident in the other. This hyper-masculinity is an in-joke, with the tongue-in-cheek implication that men are bad.

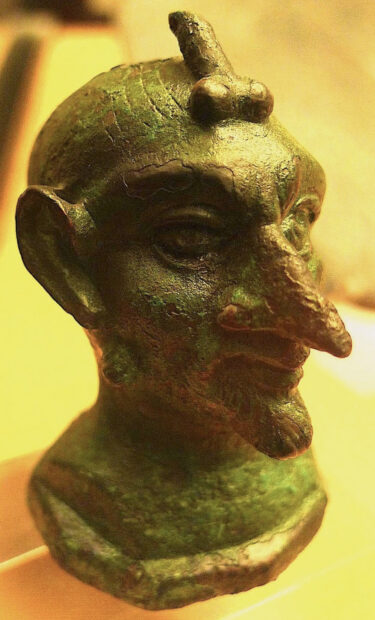

Bronze head of a phallic grotesque (probably Fascinus), Roman, 1st to 2nd c. A.D., National Museum of Archaeology, Naples. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The devil, of course, is a fallen angel. Therefore, the devil should be neuter as well. How, then, did it come to be associated with the male gender? Perhaps through association with Fascinus, the Roman embodiment of the divine phallus. Fascincus, and the phallic imagery associated with him (including winged phallus candelabras, etc.) were believed to have the power to thwart the evil eye.

The bronze head pictured above is in the “Secret Cabinet” of the National Museum in Naples. Formerly closed to the general public, this area of the museum contains ancient erotica, primarily from Pompeii and Herculaneum. When I photographed this head, the museum label said it “could hardly be ancient.” Perhaps that skepticism was based on how closely the head corresponds with modern devil imagery. When I posted my picture on an art historical website, John J. Herrmann, Curator of Classical Art Emeritus of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, informed me that he thinks the little bronze is genuine in light of the comparable examples linked below at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (lower section of painting), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

In the lower right corner of the above detail, a man’s head is outlined in glowing orange. It is a halo of death that symbolizes his transition to the spirit world. He clutches his throat as he expectorates blood. Below him, we see a man’s screaming head. His terrified eyes are rolled back to the top of his head. His body is cut off, implying that there are more suffering men beyond our field of vision.

Behind this head and the escaping spirit, a man in a torn blue shirt and blue jeans is bent over, crouching in such a way that his head is near the floor of the boxcar. He must be the sole survivor of this tragic train ride, who was able to breath through a hole in the floor.

The next man in the foreground clutches his hands to his head. He lacks a lower body, because — as noted above — he has burst, like a human firecracker, causing his soul to take flight. How better to express this almost unimaginable suffering, than to show a man who has literally exploded?

To the dead man’s left, a heavyset man grasps his throat. The orange outlines indicate that he, too, is not long for this world.

Altogether, Hernandez depicted seven of the nineteen human occupants of the boxcar. Their grimacing faces are all very similar, which is why I referred to this painting as a Masque of Death in my 2004 text. Hernandez might have come to view this similitude as a defect. In any case, he introduced a more varied cast of sufferers in the second version of this painting, which I discuss below.

I see the unmistakable influence of the Neo-Mexican artist Alejandro Colunga in these faces, especially the orange ones. Colunga was one of the hottest Mexican artists in the 1980s and early 1990s. Martinez, who was Hernandez’s next-door neighbor, recalls that Colunga exhibited in San Antonio several times. Colunga was also one of the artists represented by the Jansen-Pérez gallery in San Antonio that also represented Hernandez and Martinez. The gallery subsequently opened a branch in Los Angeles, where Hernandez worked creating paintings for director Taylor Hackford’s film Blood In, Blood Out, which was released in 1993. (For the gallery, Hernandez’s relationship to it, and his contract for the film, see my Hernandez, Part 1.) In Los Angeles, Hernandez would have had additional opportunities to see Colunga’s works in person, as well as illustrations in magazines and catalogs.

Colunga was a self-taught artist who employed a wide range of styles and techniques. Many of the faces Colunga painted are framed in a bright halo of color, with small rays emanating from a bright outline. Colunga liked orange and black contrasts, sometimes in faces, which often seem to be blackened or burned. Some of these faces are wrinkled. I think Hernandez got the idea of alternating black and orange contrasts from Colunga. Colunga’s influence also explains the black face of Hernandez’s departing soul — it is burned to a crisp.

Alejandro Colunga, “Sálvanos” (Save Us), 1990, oil on linen, private collection. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Sometimes entire figures in Colunga’s paintings are burned to an emphatic three-dimensional crisp and are outlined in dramatic red-orange. One pertinent example is his magnificent Save Us, in which even the Virgin of Guadalupe is burned. I wrote the following account of Save Us in 2011:

Alejandro Colunga takes up the Guadalupe theme in Save Us (1990). This painting revisits Guadalupe’s apocalyptic roots in Revelation 12:1: the “great sign” in heaven of “a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet.” The Biblical apocalypse is usually interpreted as the final cosmic battle between good and evil. Colunga’s apocalypse looks like an atomic one. The entire world is a living Hell. In a brilliant parody of the souls-praying-in-Purgatory motif (a popular subject in paintings and prints), the lower portion of the painting is dominated by massive, crisply burned devils and brilliant vermillion flames. The demon on the right appears to be praying to the image of Guadalupe in the upper center of the painting. Glowing white outlines delineate Guadalupe’s black face and hands. Flame emanates from her crown, as though she were burning like a candle. Behind her red-orange mandorla (the luminous cloud that envelops her) is an even brighter, white-hot “glory,” like the cloud from an A-bomb blast. Skyscrapers topple on the right, while a plane plunges downward. On the left, a man carries a burning house, while a rabbit leaps out of the frame. These blackened forms are defined by the flames that consume them.

Alejandro Colunga, “Sálvanos” (Save Us) (detail of upper section, slightly cropped on sides), 1990, oil on linen, private collection. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Despite the skull and bone motifs on her dress, Colunga’s Guadalupe is still Mexico’s protectoress: the banderoles hanging from her wrists prove it. The “original” Guadalupe, the statue in the sanctuary in Extremadura, Spain, is a “black” virgin. The Mexican Guadalupe, beloved by Mexicans and Chicanos in part because she was a “brown” virgin, is now so crisply cooked that she approaches the black color of her namesake. This is one of the many products of Colunga’s childhood encounter with sanguinary religious statues and human relics. (Published in Spanish in “Mestizaje, mexicanidad, y arte neomexicanist y chicano,” in Luis Miguel Leon and Josefa Ortega, eds., ¿Neomexicanismos? Ficciones identitarias del México de los ochenta. Mexico City: Museo Moderno, 2011.)

Alejandro Colunga, “Sálvanos” (Save Us) (detail of upper section, slightly cropped on sides), 1990, oil on linen, private collection. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

But there are very important differences between Colunga’s and Hernandez’s works in mood and tone. Colunga’s are generally playful, childish, and faux-naïve. Imagine a child who loved clowns, toys, horror images, and religious images, and didn’t understand that there were any differences at all between them. Colunga, for instance, sometimes combined clown and circus imagery with representations of Christ. Hernandez, on the other hand, used the elements he derived from Colunga to create an image of suffering so extreme that it is hard for most people to even look at his painting. (Visitors to my 2004 exhibition frequently made this remark.) Moreover, unlike images of tormented saints or historical martyrs, Hernandez is depicting a contemporary event — one that could very well be reoccurring somewhere in South Texas at this very moment in time.

A parallel can be made between Hernandez’s utilization of the techniques and imagery inspired by Colunga and Carlos Almaraz (for the latter, see my Hernandez, Part 1). Both Colunga’s and Almaraz’s works are generally upbeat (or, in Colunga’s case, playful rather than seriously grim). Hernandez, who was not a rote appropriator of influences, transformed elements he liked in Almaraz and Colunga into paintings that were dark and horrifying. I don’t think Hernandez ever painted anything quite as grim, harsh, and unrelenting as his two versions of Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar.

Given Hernandez’s great love of film — especially film noir — we should note that the film noir genre has roots in both horror and German Expressionism. Horror films are certainly relevant to Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar. Hernandez’s painting is like a still from a horror film in which several people are dying from a pain-inducing poison they imbibed simultaneously. Most painters, on the other hand, generally represent a diverse range of effects in a single canvas. The extremely dramatic expressions and gestures of Hernandez’s protagonists harken back to silent film, when facial expressions and gestures had to convey nearly everything. Hernandez has given us simultaneous paroxysms of death.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (non-photoshopped image), 1993, oil on canvas, collection of Fil and Rose Vela.

The space of Hernandez’s painting is distorted and compressed. The slats in the rear are extremely warped, especially in the area that extends from the angel’s hand to her head. The left side of the boxcar does not meet the rear side squarely because the left side follows the cantilevered contour line of the angel’s shoulder. Hernandez made a specialty of painting crooked buildings and structures, which I trace back to Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) (see my discussion in Hernandez, Part 1).

In the above photograph, provided by the collectors of the piece, the bottom portion of the canvas is skewed. One can see the framing device Hernandez utilized: on each side of the canvas, he has painted metal strips held by screws. Similar metal strips will have much more significance in the second version of this painting.

Hernandez’s Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar, 2010

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar,” 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

I admired Hernandez’s first version of Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar, and I always encouraged him to paint another version. But when he finally did, I was no longer living in San Antonio. I have never seen this painting in person, though Hernandez described it to me on the telephone. I am grateful that the owner, Paul Dunlap, has discussed several aspects of the painting with me, which I relate below.

The second version of Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar reflects the artist’s stylistic evolution. The first version was very thickly painted, with more solid forms throughout. The 2010 version is more thinly painted, but with higher-keyed color and some very dramatic chiaroscuro (light-dark contrasts), though not in the orange faces, which have less contrast as well as physical substance. Dunlap reports that some areas have considerable textures, such as the sacred heart, and that the areas that feature splattered blood “are always three-dimensional.” In addition, paint-splatter effects and short, spider web-like lines are distributed throughout the surface of the second painting.

Alejandro Colunga, “El mago de la lluvia” (The rain wizard), 1988–1988, oil on canvas, private collection. Photograph: artnet.

Hernandez has swapped effects he found in Colunga’s work in the two versions of Diez y ocho illegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar. As discussed above, in the earlier version of this theme, Hernandez uses thick layers of contrasting orange and black colors, as well as halo effects very similar to those used by Colunga.

But in the 2010 iteration, both the contrasting features and the halo-like effects around these two faces are rather unlike Colunga’s example in Save Us and other paintings that exhibit such features.

Nonetheless, the manner in which flecks of paint are splattered all over the canvas in the 2010 version of Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar bears comparison with many of Colunga’s paintings. This includes The Rain Wizard, wherein multi-colored drops of rain (and milk from a multi-breasted, two-headed creature) fill the picture space.

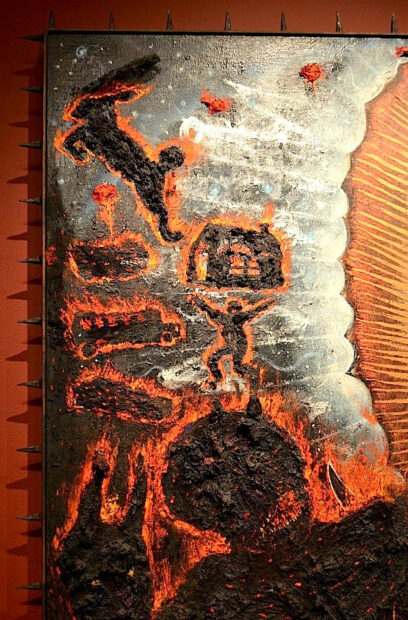

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of rear of boxcar), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

The second version of Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar employs a more rationalized conception of space. The sides of the truck meet at vertical intersections in the rear. Even though the elongated left side distorts the perspective somewhat, it does not collapse in the center, as it seems to in the earlier version of the painting.

As noted above, the 1993 iteration has studded metal strips on the far sides of the canvas that serve as framing devices. In the 2010 version, the metal strips demarcate the edges of the respective sides of the truck’s interior.

Most importantly, the metal strips in the center of the painting form a dramatic cross — that is why Hernandez did not make this interior crooked, as he had in the earlier painting, and as was his general tendency.

The excessive size and number of screws call attention to this metallic border. It almost has a pseudo-Gothic quality, like an over-the-top custom van interior. I think the artist was at pains to make the central motif as attention-getting and as legible as possible. Dunlap notes: “when you focus on the cross, the whole thing looks more three-dimensional.”

The metal chain that is attached to the metal cross evokes the attributes of Christ’s crucifixion that are sometimes painted on or emblematically attached to crosses in Catholic churches. These include the ropes that bound Christ’s hands, or the crown of thorns that was placed on his head. A flaming, bleeding sacred heart serves as a beacon. It is suspended just above the cruciform intersection of metal strips that forms the cross. Such hearts are also emblematically associated with crosses.

The padlocked chain emphasizes the fact that the inhabitants are incarcerated, even though they entered into the boxcar voluntarily. Chains are also evident in the far left of the painting.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of heart dripping blood on padlock), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Paul Dunlap.

In a dramatic gesture, the heart, in fact, drips blood directly on the padlock.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of upper left), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

In the upper-left corner, one can see the feet and the bottom of the Virgin of Guadalupe’s gown as she touches the moon with her toes. Whereas the sacred image in Mexico City has embroidered roses on her pink dress, Hernandez has instead painted jalapeño peppers. Martinez notes this element is “appropriate if you are throwing in everything that suggests the overheated circumstances.” As we have seen, Colunga substituted skulls and crossbones for the embroidered roses, so this is another example in which Hernandez appears to be following Colunga’s lead.

This Virgin of Guadalupe evidently has the power to pass through the boxcar’s roof. Her presence confirms that the moon in the first version of the painting references the Virgin of Guadalupe. But in the 2010 version, it is unclear whether she is coming or going. Hernandez sometimes enjoyed creating situations with religious ambiguity. Is the Virgin alighting on the moon to save the man’s soul, or is she deserting him in the hour of his greatest need, when she should be consoling him? Or is the man hallucinating this detail, in a final paroxysm of delirium? Is salvation, again, just out of reach, or is this the moment of deliverance, the reward for a lifetime of faith?

Gentle rays are emanating from the moon, bathing the lower contours of the man’s arms with a beautiful white light. This light — the most beautifully painted section of the picture — could be interpreted as a representation of grace. But at the same time, the man, whose head is tipped sharply backward, is spewing blood and sweat like a human fountain.

As Cesar Martinez commented to me about this painting:

Specific to this painting, the sweat and blood doesn’t just drip, it sprays out and very effectively expresses the kind of anguish one can imagine a spasmodic, quivering human body goes through in those circumstances. More generally, Adan’s work has a quality of expressiveness that utilizes bright glare exploding off surfaces, cigarettes glowing, the fiery blast of gunfire, moonlight, and neon signs.

Additionally, Hernandez has peppered the surface of the painting with dashes, little lines, and scribbles that do not denote anything in particular. These marks enliven the surface of the painting and served to knit forms together, like strands of webbing shot out by a spider.

The seven humans in the 2010 painting are posed in much the same manner as they were in the 1993 painting. More of the figure that stands under the crescent moon is depicted. He appears to be pressing against the boxcar’s ceiling. This pose creates a claustrophobic effect, making it seem as if one cannot even stand up in the boxcar.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of devil and door), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

Instead of a fully outlined figure, the devil is represented in the 2010 painting by a disembodied head. He has been decapitated, which is why his neck drips blood, which streams down the door.

The devil is, nonetheless, still very powerful, as is evident by the fact that he breathes fire and emits a cloud of smoke — as if more heat and more oxygen consumption were needed in this hellscape.

Significantly, he is breathing fire at the intersection of the metal strips that form the cross of steel. The devil is attacking the cross rather than any of the inhabitants of the boxcar. Moreover, the smoke he emits will surely dim the glow of the sacred heart that functions like a holy street lamp. The devil’s red face and his yellow flames are reflected in the areas adjacent to him.

Just below this devil head, one can make out a skeletal figure in a black robe. Since Hernandez positively identifies this figure as Santa Muerte — rather than the Grim Reaper — in an earlier painting (see my Hernandez, Part 1), we can be confident that it is meant to stand for Santa Muerte in this one. I have found no evidence that Hernandez was a devotee of Santa Muerte. Rather, as Jesse Borrego (who played the role of the artist named Cruz in Blood In, Blood Out) has suggested to me, Hernandez probably became interested in the Santa Muerte phenomenon when he was in Los Angeles doing research for the film. In this painting, it serves as another layer of occult meaning, one that is small and subtle, almost hidden.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of heavyset man, exploded man, dead man, ghostly angel, and mourning woman), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

In the 2010 version of Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar, the angel is reduced to a small figure rendered in white outline. She is bent over in mourning, hovering above a dead man who has already turned blue. This tiny, greatly undersized figure is crammed into the space formerly occupied by the entrails of the exploded man’s corpse. The little dead man is rather reminiscent of a dead Christ. Blood streams from his eyes and mouth, and he even seems to have a wound in his side. The conjunction of dead man and mourning angel creates a pieta scenario.

Dunlap recalls that Hernandez told him that he didn’t think the first version of the painting had enough people in it, so he added more figures to the second version.

Just behind the transparent angel, a woman in a ragged blue dress holds her head in her hands, no doubt regretting that she entered the boxcar. Note how much larger she is than the dead man who lies in front of her. Hernandez enjoyed violating perspective and scale.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of lower portion of painting), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

On the far right, one can see a praying woman or girl, who has taken the place occupied by the devil in the 1993 painting.

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of screaming man and praying woman), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

Her positioning is reminiscent of that of the praying devil on the right side of Colunga’s Save Us, which also has greatly elongated, pointy fingers.

The screaming man is now blue instead of the ruddy flesh color he was in the first painting. His blue jeans almost suggest black lungs. For some unspecified reason, the two women in this painting do not suffer the respiratory distress that is killing the men. Are they meant to be real, or are they merely imaged by the dying men?

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of sacred heart and small Virgin of Guadalupe), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

Finally, let us consider the upper right portion of the painting. The flaming sacred heart provides illumination, and it stands against the fire-breathing devil head, which sends smoke in its direction to snuff it out like a candle. The tiny Virgin of Guadalupe has a face that has been burned to a crisp — her face is far darker than the one in Colunga’s Save Us. As the Virgin floats above the screaming man, the praying woman seems to be appealing to her. Dunlap remembers that Hernandez explained that “the Virgin’s face is blacked-out because she wasn’t responding to the woman’s prayers.”

Why are there two Virgin of Guadalupe images in this painting? Is one not enough? As Martinez notes: “Images of the Virgen de Guadalupe have become de rigueur, a device for some artists to use in expressing the direness of their circumstances, like in this painting. The more the better.”

Adan Hernandez, “Diez y ocho ilegales Pressure-Cook in a Boxcar” (detail of upper right, with shadowy hands of the devil pursuing the fleeing soul), 2010, oil on canvas, 54 x 84 inches, collection of Paul Dunlap. Photograph: Facebook.

Christianity is a religion that pits absolute good against absolute evil. The point of this perpetual struggle is the battle for souls. Is there an escaping soul in this painting? If so, where is it, and who is going to get it?

If we recall the pointy hand of the devil in the earlier painting, then we can understand that the two shadowy forms (one underneath the Virgin, and the other above the praying woman’s head) can be interpreted as the hands of the devil. I suspected that the tiny form above the praying woman’s head is a soul — it looks like a skull shrouded in black. Dunlap confirms that it is a little skull. Then, surely, this is what the devil’s shadowy hands are reaching for. And he doesn’t seem to have any competition for this prize.

Dunlap hangs Hernandez’s painting just outside his office door. He reports that many visitors are initially “taken aback” when they see it. He often has to explain what the painting depicts. Dunlap says the painting “is a constant reminder of how fortunate I am.” When he looks at the painting, he sees “what others risk just to have the opportunities we have here.”

The Historical Roots of the Asylum and Immigration Crises in the Americas

In addition to the two paintings by Adan Hernandez, the 1987 boxcar tragedy also inspired Sylvia González Scherer to become a playwright when, as she told the Central Oregonian, the details of the tragedy were recounted in a television news story in the same monotone as the weather report. Her play Boxcar (El Vagon) has been produced in Spanish as well as English.

Unfortunately, senseless U.S. immigration policies make migrant deaths as inevitable as changes in the weather. Since the Border Patrol’s fatality count is basically a tally of corpses and human remains, some hold that its count is only a fraction of the real total, which includes migrants drowned in the Rio Grande and lost in the desert.

But let us take a step back and look at why the number of immigrants and asylum seekers is so high from certain Latin American countries.

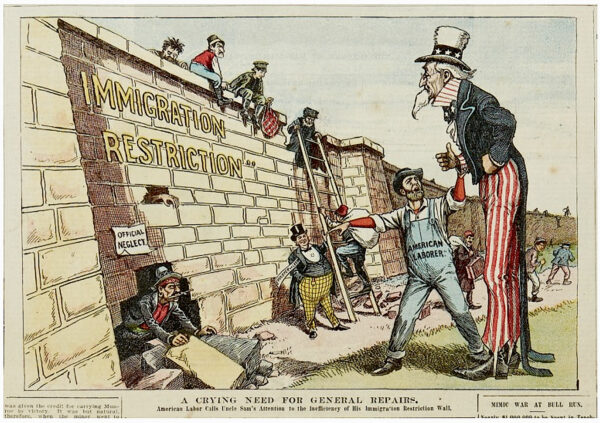

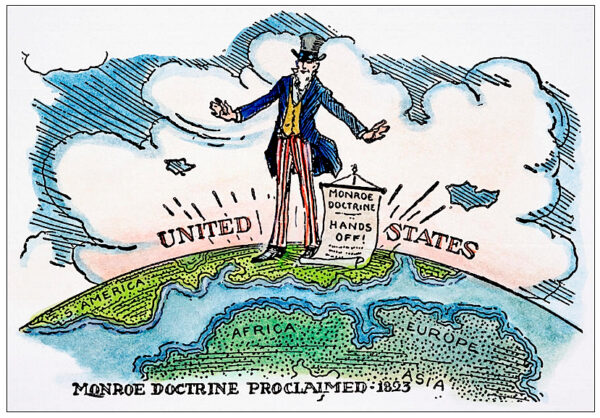

The first step is to acknowledge that the U.S. has regarded the entire hemisphere as its domain, something made explicit in the Monroe Doctrine. Announced in 1823, before the U.S. was very powerful, it forbade further European colonization in the Americas. As the U.S. became a world power in the nineteenth century, it sought to control and benefit from the former European colonies in the Americas.

Various U.S. entities fomented a rebellion in Texas in 1836. This was followed by the Mexican-American War (1846-48), a war of conquest, after which the U.S. annexed half of Mexico, deliberately selecting as much of Mexico as it could get without a large population of Mexicans. See my exhibition catalog: The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (San Antonio: Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018). At the end of the century, the U.S. fought a war with Spain for the purpose of seizing its remaining colonies. The U.S. was now an empire, with overseas territories.

A cartoon by Louis Dalrymple of Uncle Sam aggressively straddling the Americas and wielding a bat labeled “Monroe Doctrine,” 1905. Photograph: Media Storehouse.

My worst fears about U.S. foreign policy in the twentieth century were confirmed by Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman in their important study, The Political Economy of Human Rights: The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism (Boston: South End Press, 1979). Little did I know in 1979 that some of the worst was yet to come during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, who was the ultimate Cold Warrior. (In my Glasstire article “Enrique Chagoya’s Super Heroes and Super Villains,” I discuss Reagan, Henry Kissinger, and George G. W. Bush as examples of the latter.)

Despite rhetoric about freedom and democracy, the U.S. has systematically destabilized and/or overthrown democratically elected governments that serve the majority of the populaces in the Third Word.

The U.S. has trained dictators, generals, soldiers, torturers, and death squad members, specifically for the purpose of installing and/or maintaining “friendly” regimes that torture and massacre their citizens when they resist authoritarian rule. At times, the worst atrocities committed by U.S.-supported regimes in Latin American countries were committed immediately after U.S.-sponsored training sessions.

I discuss this phenomenon in my Glasstire article “Enrique Chagoya 2: More Heroes and Villains,” which includes links to examples of horrific terror and sadism. Chagoya took inspiration for one of his works from an episode recounted by Chomsky in his book What Uncle Sam Really Wants (1991): A Salvadoran peasant woman discovered her mother, sister, and three children posed at a table, holding their decapitated heads with their hands. The youngest child, only 18 months old, had his hands nailed to his head so he could maintain the pose. In What Uncle Sam Really Wants, Chomsky noted a direct correlation between Latin American regimes that practiced torture and the foreign aid they received from the U.S.

The cruel policies imposed by oligarchs and repressive dictators served to create conditions that benefited U.S. corporations. These authoritarian regimes also served as Cold War surrogates and proxies against the Soviet Union after World War II. Severe political and economic oppression, in turn, have fueled refugee and immigration crises in these nations.

Juan González’s Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America (Penguin, rev. ed., 2022) begins with the European colonization of the Americas and specifically addresses the Latino population in the U.S. The just-published edition extends coverage to the 2020 elections.

González chronicles how U.S. domination — and frequent occupations — of Mexico and countries in Central America and the Caribbean resulted in millions of refugees, many of which have sought to immigrate to, or find asylum in the U.S.

González, who is a co-host of Democracy Today!, made the following statement while discussing the new edition of his book:

Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, [El] Salvador, Guatemala, these are the countries that have provided the bulk of the migration from Latin America, largely many of them fleeing from the civil wars, as in the cases of Guatemala and Nicaragua and El Salvador, in which the United States government played a key role in backing one side or the other, others coming here as a result of the needs of American businesses that established migration and recruiting. . . more so in the case of the Puerto Ricans and the Mexicans. . . . the mass migration flows of Latin Americans to this country were a direct response to the needs of the empire (quoted by the Zinn Education Project).

The Zinn Education Project excerpts a portion of González’s book that discusses the U.S. ‘s overthrow of the democratically elected government of Guatemala. Part of this is copied below:

. . . Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and C.I.A. Director Allen Dulles convinced President Eisenhower that Arbenz had to go [when President Jacobo Arbenz nationalized United Fruit Company land in Guatemala and only offered to pay the valuation the company had given for tax purposes]. The Dulles brothers. . . were former partners of United Fruit’s main law firm in Washington. On their advice, Eisenhower authorized the C.I.A. to organize “Operation Success,” a plan for the armed overthrow of Arbenz, which took place in June 1954. The agency selected Guatemalan colonel Carlos Castillo Armas to lead the coup, it financed and trained Castillo’s rebels in Somoza’s Nicaragua, and it backed up the invasion with C.I.A.-piloted planes. During and after the coup, more than nine thousand Guatemalan supporters of Arbenz were arrested.

Diego Rivera, “Gloriosa Victoria,” 1954, oil on linen, collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photograph: Mark Vallen’s Art for a Change.

In Rivera’s painting, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles grasps the fins of a bomb inscribed with the face of President Eisenhower, as he shakes the hand of coup leader Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas. The pocket of his Eisenhower jacket bulges with cash. C.I.A. director Allen W. Dulles (in a black suit) dispenses cash, which U.S. ambassador John Peurifoy helps distribute to the military. Mariano Rossell Arellano, the Catholic Archbishop of Guatemala, gives his blessing to the coup (he had lent his name to a C.I.A.-authored leaflet that endorsed the coup). A dismembered child lies under the bomb. Other dead children and bound, assassinated workers lie in the foreground (landowners had the right to execute their workers). In the left background, workers load bananas onto a U.S. cargo ship. In the right background, the people rebel (President Arbenz, the nation’s second democratically elected president, had wanted to arm a popular front to safeguard the government, but he was unable to do so). The Guatemalan army could easily have defeated the U.S.-backed forces, but soldiers refused to fight because they feared a U.S. invasion. John Foster Dulles referred to the coup as a “glorious victory for democracy,” which inspired Rivera’s title.

The excerpt from Harvest of Empire continues:

Despite the violent and illegal manner by which Castillo’s government came to power, Washington promptly recognized it and showered it with foreign aid. . . . Castillo quickly outlawed more than five hundred trade unions and returned more than 1.5 million acres to United Fruit and the country’s other big landowners. Guatemala’s brief experiment with democracy was over. For the next four decades, its people suffered from government terror without equal in the modern history of Latin America. As one American observer described it, “In Guatemala City, unlicensed vans full of heavily armed men pull to a stop and in broad daylight kidnap another death squad victim. Mutilated bodies are dropped from helicopters on crowded stadiums to keep the population terrified . . . those who dare ask about ‘disappeared’ loved ones have their tongues cut out.”

Diego Rivera, “Gloriosa Victoria” (detail of center), 1954, oil on linen, collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photograph: Mark Vallen’s Art for a Change. For additional photographs, see Art for a Change.

For another treatment of the Guatemalan coup (and history prior to the coup), I recommend a podcast from Blowback’s second season, which examines Cuba. The bonus episode, titled “Red-Handed Sleight of Hand,” addresses Guatemala. Che Guevara was in Guatemala at the time of the coup, and the coup’s success affected strategies employed during the Cuban Revolution. The podcast notes that the death squad phenomenon that has plagued Latin America began in Guatemala. It also points out that the C.I.A. compiled a hit-list, but was unable to determine whether the people on it had been executed after the coup.

For a video on the Guatemalan coup with a great deal of documentary footage, see: Jake Tran’s “Oh, so this is why people hate America!” (2022).

Greg Grandin notes that John P. Longan, a U.S. Border Patrol agent active in a brutal Mexican repatriation action in California called “Operation Wetback” (more on that below), moved to the state department and trained Guatemalan police and military. In early 1966, Longan’s “Operation Clean-Up” made more than 80 raids and assassinated many targets, including more than 30 political activists in four days. See Grandin’s article “The Border Patrol has been a Cult of Brutality Since 1924,” (The Intercept, January 12, 2019).

Grandin, who is an expert on Guatemala, used it as a case study in his book The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War (University of Chicago Press, second edition, 2011), which discusses Longan at length.

Juan González’s book was made into a 2012 documentary film directed by Eduardo Lopez and Peter Getzels called Harvest of Empire: The Untold Story of Latinos in America (Incarcerated Nation Network INC Media). The film addresses the political, military, and economic events in Puerto Rico, Guatemala, Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador that have caused refugee and immigration crises.

During the June 13, 2022 Democracy Now! program (which discusses the new edition of González’s book), co-host Amy Goodman noted:

Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, reports a record 234,000 migrants and asylum seekers arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in April alone. More than a quarter of the world’s migrants are in the Americas — some 73 million people — even though the hemisphere accounts for only 12% of the world’s population, this according to the International Organization for Migration. Millions are displaced in their own countries by poverty and violence.

The United States, of course, has played an important role in creating — and maintaining — that poverty and violence.

The Bracero Program, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, and the “Illegalization” of Mexican Migrants

For a short history of immigration/nationalization laws from 1790, see Susan E. Stutz’s “The Golden Door” (October 15, 2021, Resistbot). We’ll jump ahead to the twentieth century.

Mexican migrant workers, who had played an important role in railroads and agriculture from the 1880s to the 1930s, were forcibly deported during the Depression.

Then, during World War II, a severe labor shortage led to the Bracero Program, which provided a legal mechanism for millions of Mexican migrants to work in the U.S. from 1942 to 1964. Numbers peaked in 1950, with 450,000 Bracero Program workers (in addition to a sizeable number of unauthorized immigrants). For the Bracero Program in Texas, see the Handbook of Texas Online.

During a post-Korean War recession, 1-2 million Mexicans and American citizens of Mexican descent were forcibly deported to Mexico in 1954-55 in a military-like campaign known as Operation Wetback. See Immigration History’s website.

As noted above, John P. Longan (who had been a senior Border Patrol inspector in El Paso) went from Operation Wetback to the state department, where he trained and led death squads in Third World countries. Latin American death squad trainees, until the early 1970s, studied at the Border Patrol academy in Los Fresnos, Texas (see Greg Grandin and Elizabeth Oglesby, “Washington Trained Guatemala’s Mass Murderers—and the Border Patrol Played a Role,” The Nation, January 3, 2019).

Grandin says the Border Patrol is arguably “the most politicized and abusive branch of federal law enforcement” (“The Border Patrol has been a Cult of Brutality Since 1924,” The Intercept, January 12, 2019).

In the above article, Grandin notes that, at its inception in 1924, the Border Patrol was controlled by White supremacists (including Klu Klux Klan members), and was made into “a frontline instrument of race vigilantism” that utilized beatings, murder, terror, rape, and torture. Grandin details numerous abuses by members of the agency through the decades.

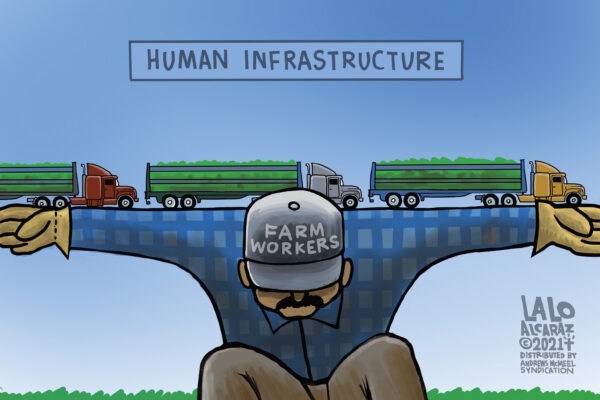

When the bracero program was ended in 1964, an inadequate H-2 visa guest worker program took its place. But the most comic attempt to replace migrant Mexican workers happened in 1965, when Secretary of Labor W. Willard Wirtz proposed what he called the A-TEAM. It stood for Athletes in Temporary Employment as Agricultural Manpower. Announced with great fanfare in the presence of some major professional athletes, the story ran in numerous newspapers on Cinco de Mayo. Few of the students who signed up for the program ever saw the fields, which was fortunate, since those who did quickly experienced the harsh circumstances of field work firsthand. See Gustavo Arellano’s entertaining article, “When The U.S. Government Tried To Replace Migrant Farmworkers With High Schoolers,” (August 23, 2018, npr).

Importantly, farm workers in significant quantities are needed at highly specific places at highly specific (and usually very limited) times of year. When they are not available in sufficient numbers at harvest time, several months of work and investments — at the very least — are lost. For a recent video on the current shortage of farm workers, see the 2021 CBS Sunday Morning video “Down on the Farm: a Shortage of Agricultural Labor.”

For a discussion (and visualization) of how difficult farm work is, and how the harvesting of particular crops requires specific skills, see the video “What everybody gets WRONG About Farm Work.”

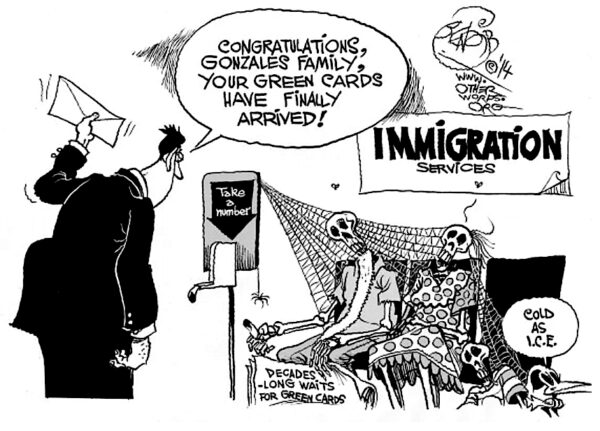

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 replaced a system in which 70% of visas had been reserved for immigrants from the U.K., Ireland, and Germany by putting a 20,000-person cap on each country. In conjunction with the elimination of the Bracero Program, this left hundreds of thousands of migrant workers from the Americas with no authorized means of entry into the U.S.

A KAL cartoon showing an immigrant child portrayed, alternately, by a donkey and by Trump, as someone in need welcomed by the outstretched hands of Uncle Sam, and as a demon, 2018. Photograph: The Economist.

As Douglas S. Massey notes in a 2015 Washington Post article called “How a 1965 immigration reform created illegal immigration,” the bill was intended to end a virtual ban on Asian and African immigration and to offer equal opportunities with an equal number of visas to each country.

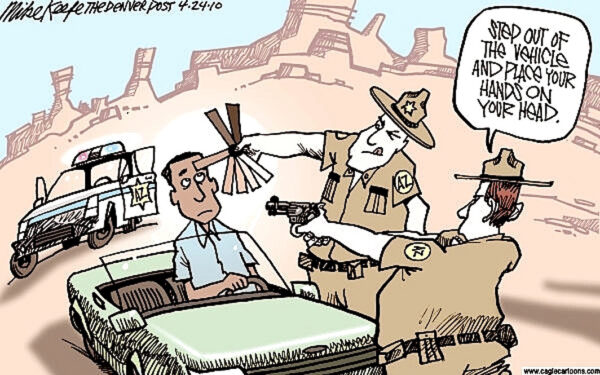

At this time, Mexico’s and the U.S.’s economies were becoming more deeply connected. As Massey points out, this meant that “the same migrants were leaving the same communities to go to the same employers in the same U.S. states in about the same numbers.” Crucially, however, these migrants were now deemed “‘illegal’ and hence by definition ‘lawbreakers’ and ‘criminals.’” Over time, this change in semantics brought about a momentous change in the perception of immigrants.

The legal demonization of migrants had begun. This demonization would have significant ramifications as politicians increasingly vilified immigrants in order to achieve electoral success. By definition, unauthorized migrants were criminals who were increasingly characterized as dangerous invaders. In order to block or defeat these invaders, the border itself would become militarized like a war zone.

Massey points out that the “illegal invasion” of largely Mexican migrants came to be associated with perceived national security threats: communism in the 1980s, illegal drugs in the 1990s, followed by al-Qaeda in the 2000s and Ebola in the 2010s. To these, we can add ISIS and COVID-19. Monkey Pox and other paranoias de jure will surely be next.

In the public imagination, Mexicans have become the bearers of all ideological, material, and medical contagions that threaten the U.S. body politic.

Why U.S. Immigration Policies Do Not Work: From Reagan to Clinton to Trump

In their comprehensive 2016 article “Why Border Enforcement Backfired” (this is a link to the authors’ manuscript rather than to the paywall-protected article in the American Journal of Sociology), Douglas S. Massey, Jorge Durand, and Karen A. Pren examine the unintended consequences of U.S. emigration laws. They conclude that border militarization transformed “undocumented Mexican migration from a circular flow of male workers going to three states into an eleven-million person population of settled families living in 50 states.” When border militarization made it increasingly difficult to cross the border, male migrants stayed in the U.S. instead of returning to Mexico. Many were subsequently joined in the U.S. by additional family members.

Reagan’s record on immigration issues is better than most would assume — especially since his authority is constantly invoked by Fox News and right wing extremists.

In a 1980 Republican Party forum, both Reagan and George H. W. Bush gush about the positive qualities of “illegal aliens.” In this short Time magazine clip, Bush concludes: “…we’re creating a society of really honorable, decent, family-loving people that are in violation of the law. …These are good people, strong people. Part of my family is Mexican.” Reagan replies: “Rather than… putting up a fence, why don’t we… open the border both ways… .”

In the article cited above, Massey, Durand, and Pren note:

The most prominent politician contributing to the Latino Threat Narrative was President Ronald Reagan, who in 1985 declared undocumented migration to be “a threat to national security” and warned that “terrorists and subversives [are] just two days driving time from [the border crossing at] Harlingen, Texas” and that Communist agents were ready “to feed on the anger and frustration of recent Central and South American immigrants who will not realize their own version of the American dream.”

Reagan, who was never a proponent of wall building, didn’t characterize Latinos as a Brown Peril, though he thought they could be manipulated by communists.

Nonetheless, the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (also known as the Simpson-Mazzoli Act and the Reagan Amnesty) that Reagan signed into law permitted a record number of unauthorized immigrants — almost three million — to achieve legal status. These immigrants had to prove that they were in the U.S. continuously since 1982. The law also called for employers to confirm the legal status of their workers, and it provided criminal penalties for those who knowingly hired unauthorized workers. The Republican solution for enforcement — a national I.D. — was removed from the bill. See the Library of Congress research guide on this subject.

A 2010 NPR program (“A Reagan Legacy: Amnesty for Illegal Immigrants,” npr, July 4, 2010) notes Reagan’s statement in a debate with Walter Mondale in 1984: “I believe in the idea of amnesty for those who have put down roots and who have lived here, even though sometime back, they may have entered illegally.”

The NPR program featured Reagan’s former speechwriter, Peter Robinson, who said: “It was in Ronald Reagan’s bones — it was part of his understanding of America — that the country was fundamentally open to those who wanted to join us here.” NPR also interviewed Alan Simpson, who, as a Republican Senator from Wyoming, co-sponsored the 1986 bill. According to Simpson, Reagan “knew that it was not right for people to be abused… Anybody who’s here illegally is going to be abused in some way, either financially [or] physically. They have no rights.”

Greg Grandin, author of The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (Metropolitan Books, 2019), chronologically assesses presidential administrations in his article “The Militarization of the Southern Border Is a Long-Standing American Tradition” (January 17, 2019, NACLA). (All of the Grandin references I make below are to this article.)

Grandin notes that in 1979, President Jimmy Carter proposed border walls in some areas (a plan he subsequently withdrew). Reagan strongly opposed building “a nine-foot fence along the border between two friendly nations” in 1980. In 1984, however, Reagan greatly increased the size of the Border Patrol. He also sent federal agents to find unauthorized workers and deport them in Operation Jobs. Reagan also supplied high tech equipment to the border, including ground sensors, night-vision goggles, infrared scopes, and spotter planes. So, although he consistently opposed walls, Reagan laid some of the groundwork for the militarization of the border.

Grandin notes that in 1989, President George H. W. Bush made a short-lived proposal for a border trench (mocked as a “moat”) south of San Diego. In 1992, Patrick Buchanan’s strength in the Republican primary resulted in the call for a border “structure” as part of the Republican platform, which Bush did not support.

The most extreme and dramatic shift in border policy took place under President Bill Clinton. As I noted in my Glasstire article “Felipe Reyes, Part 3: Struggles in Pharr and San Antonio; Race, Trump, and the 2020 Election” Thomas Frank has argued convincingly that Clinton’s biggest successes (NAFTA, the 1994 Crime Bill, bank and telecom deregulation, welfare reform, and the balanced budget) were longstanding Republican objectives. All were harmful to the poor and the working class. In that article, I also note that Clinton, who was a greater border issue “hawk” than his Republican opponent Bob Dole, nonetheless won 72% of the Latino vote in 1996.

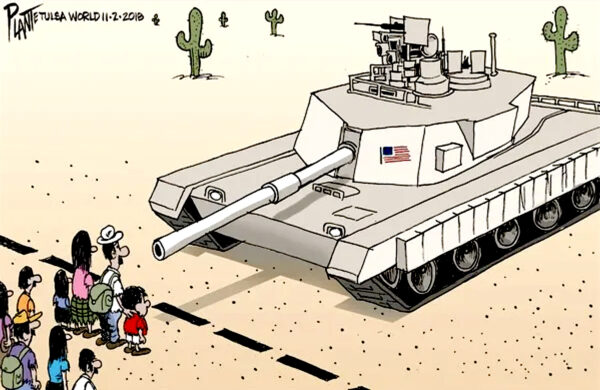

A Bruce Plante cartoon of tank pointing at immigrants at the U.S.-Mexican border, 2018. Photograph: Tulsa World.

Border militarization is yet another area in which Clinton successfully passed legislation favored by Republican zealots.

That legislation took the form of Operation Gatekeeper in late 1994. It entailed a greater number of border guards and an increased budget, which provided for more high tech equipment, including thermal-imaging devices and software that enabled biometric scanning of the migrants that were apprehended.

Clinton built hundreds of miles of walls and more checkpoints that extended inland from the border. Grandin notes that one stretch of wall in California was made from Vietnam-era helicopter landing pads, with sharp edges that severed migrants’ fingers. Clinton’s administration directed immigration streams to more dangerous crossing areas, primarily deserts (where sand temperatures could reach 150 degrees). Grandin points out that Clinton’s immigration commissioner referred to this deadly geography as an “ally.” Also see the criticism of Operation Gatekeeper by the Southern Borders Community Coalition website.

Like the nation’s military budget, the apparatus of the militarized border (walls, checkpoints, technology, hardware, software, border enforcement officers, internal policemen, etc.) always gets bigger, no matter how ineffective it is. Its very ineffectiveness, in fact, is taken as proof of the need for even more “enforcement” expenditures.

For the effects of border militarization in Arizona and Texas on immigrants and asylum seekers, see the 2021 Vice News video: “The Human Costs of Hardening the U.S. Mexican Border.”

For a range of views from vigilantes to good Samaritans in Arizona, see The Times and the Sunday Times video “Hunting Humans: The Battle on the U.S. Border.”

Massey, Durand, and Pren note that all this enhanced militarization and border enforcement had “no effect on the likelihood of initiating undocumented migration,” though it increased both the risks (due to dangerous means of concealment, or longer, more hazardous routes through the desert) and the costs of migration (smugglers became more necessary, and lengthier routes cost more money).

Since, in the U.S., politics is bound into the straightjacket of a two-party system, it is not possible for Democrats to outflank the Republicans on the right. After Clinton signed into law key portions of their agenda, many Republicans only became more extreme, ultimately losing touch with reality, especially in Trump’s world, on issues such as the border wall, climate change, COVID-19, and “stolen” elections.

Noam Chomsky, in a 2009 lecture called “The Unipolar Moment and the Obama Era” at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), connected the North American Free Trade Agreement, Operation Gatekeeper, and the militarization of the border:

As NAFTA went into effect in 1994, President Clinton also instituted Operation Gatekeeper, which militarized the Mexican border. As he explained, “we will not surrender our borders to those who wish to exploit our history of compassion and justice.” He had nothing to say about the compassion and justice that inspired the establishment of those borders [the U.S.’s conquest and annexation of half of Mexico], and did not explain how the High Priest of neoliberal globalization . . . dealt with the observation of Adam Smith that “free circulation of labor” is a foundation stone of free trade.

Chomsky continued:

The timing of Operation Gatekeeper was surely not accidental. It was anticipated by rational analysts that opening Mexico to a flood of highly-subsidized U.S. agribusiness exports would sooner or later undermine Mexican farming, and that Mexican businesses would not be able to withstand competition from huge state-supported corporations that must be allowed to operate freely in Mexico under the treaty. One likely consequence would be flight to the United States, joined by those fleeing the countries of Central America, ravaged by Reaganite terror. Militarization of the border was a natural remedy.

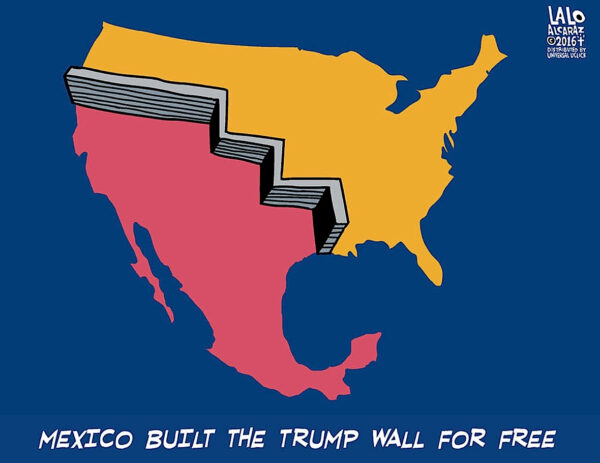

Massey, Durand, and Pren point out that between 1994 (when NAFTA was implemented) and 2010, trade between Mexico and the U.S. rose 5.3 times and tourist entries rose 12.1 times. They note: “Within an integrated economy, people inevitably will be moving.” Massey, Durand, and Pren conclude that billions have been wasted on “counterproductive border enforcement,” especially since an open border would have resulted in the permanent settlement of fewer unauthorized Mexican immigrants. Measures taken to keep “illegals” out of the country have instead served to keep these people inside the U.S. Massey, Durand, and Pren believe that the European Union has done a better job of protecting citizens and migrants, and they seem to call for the legalization of the 11 million undocumented people who reside in the U.S.

In addition to Operation Gatekeeper, Clinton promulgated the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIR) of 1996. Vox calls it “The law that broke US immigration.” IIRIR simultaneously increased the risks of deportation and made it far more difficult for deportees to obtain legal status in the future, because they had to wait outside of the U.S. for years before they could even apply for legal status. As the Vox video argues, the law “incentivized people to stay in the U.S. undocumented.”

In his 2009 UNAM lecture, Chomsky also analyzed the political and legal circumstances of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S.:

But whatever the history and the economic realities may be, immigrants have been perceived by the poor and working people as a threat to their jobs, livelihood, and life-styles. It is important to bear in mind that the people protesting angrily today have real grievances. They are victims of the financialization of the economy and the neoliberal globalization programs that are designed to transfer production abroad and to set working people in competition with each other worldwide, thus lowering wages and benefits, while protecting educated professionals from market forces, and enriching owners and managers. . . . The effects have been severe since the Reagan years, and often manifest themselves in extremely ugly ways that are featured right now on the front pages. The two political parties are competing to see which can proclaim more fervently its dedication to the sadistic doctrine that “illegal aliens” must be denied health care. Their stand is consistent with the legal principle, established by the Supreme Court, that these creatures are not “persons” under the law, hence are not entitled to the rights granted to persons. And at the very same moment, the Court is considering the question of whether corporations should be permitted to purchase elections openly instead of doing so only in more indirect ways — a complex constitutional matter, because the courts have determined that unlike undocumented immigrants, corporations are real persons under the law, and in fact have rights far beyond those of persons of flesh and blood, including rights granted by the mislabelled “free trade agreements.” These revealing coincidences elicit no comment. The law is indeed a solemn and majestic affair.

President George W. Bush doubled down on Clinton’s policies. When Bush signed his Secure Fence Act of 2006 (presidents before Trump didn’t like to call it a wall), he boasted of doubling “border security” funding and he promised to have doubled the number of Border Patrol agents by the end of his presidency. He also authorized increased utilization of satellites and drones, as well as blimps and surveillance balloons. Bush quadrupled the length of the border wall.

Gil Cárdenas, Professor Emeritus and founding Director of the Institute for Latino Studies at the University of Notre Dame, vouches for Bush’s support of immigrants:

President George W. Bush had a very favorable attitude towards immigrants. He pushed for the passage of a comprehensive immigration package in 2007. But the 9/11 attacks worked against its passage. Bush was not able to secure enough support from Republicans and from many Democrats, as well (email to the author, July 24, 2022).

His package was a far cry from Reagan’s 1986 amnesty. I quote these passages from Bush’s 2007 State of the Union:

The President Has Called For The Creation Of A Temporary Worker Program. . . . providing a lawful and fair way to match willing employers with willing foreign workers to fill jobs that Americans have not taken.

The Program Must Be Truly Temporary. Participation should be for a limited period of time, and the guest workers must return home after their authorized period of stay.

. . . The President Opposes An Automatic Path To Citizenship Or Any Other Form Of Amnesty. Amnesty, as a reward for lawbreaking, would only invite further lawbreaking.

. . . No Amnesty. Workers who have entered the country illegally and workers who have overstayed their visas must pay a substantial penalty for their illegal conduct.

. . . The program should not reward illegal conduct by making participants eligible for citizenship ahead of those who have played by the rules and followed the law. Instead, program participants must wait their turn at the back of the line.

Cárdenas clarified to me that compromises were made to try and get the plan passed against significant opposition. Only 12 of 49 Republican Senators voted for the bill, which needed 60 votes to advance. 33 of 48 Democrats supported it, including Hillary Clinton, Barak Obama, and Joe Biden. (See Donna Smith, “Senate kills Bush immigration reform bill,” Reuters, June 28, 2007.) Immigration reform never came this close again because Republican opposition to it continued to harden.

Cárdenas also stresses Bush’s anti-racist bonafides:

Bush was consistently against racism. He had been instrumental in blocking the efforts of Pete Wilson, the anti-immigrant Governor of California, in his bid for the presidency. When Bush was Governor of Texas, he signed legislation in favor of the 10% plan in public college admissions that led to more racially diverse student bodies. Bush, who thought Spanish worked well in Texas, was also very opposed to the English-only initiative that many Republicans supported.

Thus, unlike Trump, Bush was not driven by anti-immigrant or racial animus.

The 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon served as a boon to the surveillance state, resulting in the Homeland Security Act in 2003. Under Bush, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) pursued unauthorized workers all over the country.

The American Immigration Council noted in 2021 that from the inception of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003, an estimated $333 billion was spent by the federal government on immigration enforcement. This includes a billion dollars wasted on Bush’s “virtual fence,” begun in 2005 but subsequently abandoned. (“The Cost of Immigration Enforcement and Border Security,” January 20, 2021.)

The American Immigration Council also provides the following statistics: the Border Patrol budget has skyrocketed from $363 million in 1993 (early in Clinton’s first term) to almost $4.9 billion; the ICE budget has leapt from $3.3 billion to $8.3 billion; the number of Border Patrol agents was 4,139 in 1993, congress approved 23,645 for 2019, but the agency was only able to hire 19,648 at that time; the total of interior and border enforcement officers now exceeds 50,000.

See Al Jazeera’s “Walls of Shame: The US-Mexican Border,” which first aired in 2007 (now augmented with Trump cameos at its beginning and end). A Samaritan who rescues an unauthorized immigrant in this video notes that the penalty for transporting that person in her vehicle could result in penalties of five years in jail, as well as an additional ten years for conspiring against the U.S. government. So she did the same thing that vigilante migrant hunters do: she called the Border Patrol, who put the man in a bus to Mexico. The Border Patrol did not permit the man to keep the water and the socks the Samaritan had given to him.

Also see the “Dying to get through the US-Mexico border” video by Unreported World (2008). According to the video, some of the unauthorized migrants who were returned to Mexico said they were denied water by U.S. border agents. Bruce Anderson, a forensic anthropologist at the Tucson county medical examiner’s office, performs post-mortem exams on the bodies of migrants found in this jurisdiction. He notes that the pain suffered by migrants during their treks through the desert is so great that it sometimes drives them to commit suicide.

President Barak Obama did not prioritize immigration when he had substantial majorities in both the House and the Senate, so he missed his chance at serious reform. President Obama also inherited the substantial immigration security staff and infrastructure that had been built up by his predecessors, and he put it to use. He was gung-ho on enforcement, causing Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute to declare: “There are just no two ways about it: President Obama created the harshest and largest immigration enforcement regime in American history.” It is more accurate to say that Obama didn’t prevent the inherited machinery from whirring, mostly at full speed.

In his 2010 speech on immigration at American University, Obama noted the disadvantages of having 11 million undocumented immigrants that are “vulnerable to unscrupulous businesses” because they are forced to “live in the shadows.” He acknowledged: “after years of patchwork fixes and ill-conceived revisions, the legal immigration system is as broken as the borders.” But, in stark contrast to Reagan’s position that is noted above, Obama also declared: “And no matter how decent they are, no matter their reasons, the 11 million who broke these [immigration] laws should be held accountable.”

Obama’s efforts at bipartisan legislation on immigration reform were unsuccessful. In 2013, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act passed the Senate, but it was not even brought to a vote in the Republican-controlled House. In addition to even more border security measures, the bill had a pathway for legal status for unauthorized migrants who were in the country by 2011.

Latino immigration activists — like most progressive activists — were disappointed in Obama, who they dubbed “the Deporter-in-Chief,” which is one of the most memorable mocking monikers of our era. Pablo Alvarado, director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network in Los Angeles, told NPR in 2014: “I voted for President Obama, I want him to succeed, to be a champion for us, an emancipator rather than a Deporter-in-Chief.”

In 2017, another NPR program noted that a change in nomenclature (at the end of Bush’s presidency) served to inflate the number of Obama’s deportations, and that his deportations were at the same level as those of George W. Bush. Grandin concurs, though he curiously otherwise passes over Obama’s record.

With his Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) program, Obama also shielded from deportation — at least temporarily — about 750,000 people who had been brought to the U.S. as unauthorized children.

Obama also tried, unsuccessfully, to shield the unauthorized parents of children in the U.S. President Donald Trump tried to kill the DACA program, but it is still winding through the courts (as noted below).

Border Patrol abuses continued under Obama. Mitra Ebadolahi, Border Litigation Project Staff Attorney for the ACLU, summarizes some of the findings from 30,000 records (dating from between 2009 and 2014) obtained via the Freedom of Information Act. As she noted in a blog, the ACLU found

a pattern of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by Customs and Border Protection officials against child immigrants that existed long before President Trump emboldened the agency by unleashing its officers to enforce his draconian immigration policies (“The Border Patrol Was Monstrous Under Obama. Imagine How Bad It Is Under Trump,” May 23, 2018).