Dorota Biczel and I have known each other for over ten years. Oddly enough, we met in Houston over Tex-Mex at a place I cannot remember. We were both students in Austin at the time, and a few of us came down for a weekend to see art things, go to talks, and enjoy what a diverse city looks like. And as luck would have it, we ran into another group of students (mostly grad students) who were doing the same. Together we ate chips, salsa, and tried to imagine what our post-school life would be like.

Who knew ten-plus years ago that we would end up here? With a few glasses of wine, a beautiful patio, cigarettes, and cigars, Dorota and I discussed her year as the Executive Director of Houston Center for Photography, the ups, the downs, a little bit of politics, and her practice as an art historian.

Biczel with artist Nancy La Rosa and artwork by Edi Hirose at the opening of “Moving Mountains: Extractive Landscapes of Peru” (September 23–December 10, 2016) at the Visual Arts Center, Austin. Personal archive

Carris Adams (CA): Admittedly, I know very little about your research. What I understand it to be is an investigation in how Latinx Contemporary Art is used to shape and reshape emigrant/immigrant communities.

Dorota Biczel (DB): What is most interesting for me in studying Latinx Contemporary Art or Art of the Americas is that it is a very particular case study for the larger issue of how artists contend with diasporas and displacements. I am interested in art that is a tool for social imagination in the contexts when a social body needs to urgently reimagine itself. And of course, this issue is always incredibly contextual and dependent on the particular flow of humans, cultures, politics, climate, etc.

I am interested in the kind of art that sets as its goal the reimagination of the social. We could talk much about it because there are many nuances, but — in short — I found just an absolutely fascinating case study in contemporary Peru, specifically in Lima. In the second half of the 20th century, it was one of the fastest growing [Latin American] cities because of internal migrations of indigenous people — mostly from the Andes and the Amazon— from rural areas into the city. With such a rate of expansion, in English, we would call it a “demographic explosion.” In Peruvian Spanish vernacular, they speak about a “demographic avalanche,” which is an interesting metaphor for the movement from the mountains to the coast.

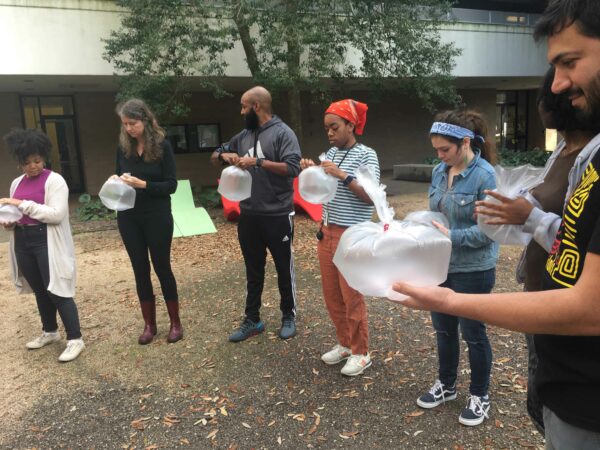

Biczel’s students at the University of Houston performing exercises based on Lygia Clark’s “relational objects,” fall 2019. Photo: Biczel’s personal archive

CA: Do they say this as something that is positive or negative?

DB: It’s interesting. Like many metaphors, it is a double-edged sword.

CA: Exactly. One can imagine an avalanche as a fascinating thing, but it is also terrifying.

DB: What also makes displacement interesting is that you have mostly these indigenous migrations into the city that grows five times in about 20 years. Because these migrations are closely tied to social movements, specifically peasant movements, they coincide with tumultuous clamoring for political change. By 1980, the country is supposed to return to democracy after a period of military dictatorship, and this pushes many socially engaged artists to become attuned or willing to participate in this particular transformation.

When I speak about social movements, they are class-based and culturally based; there is still fairly emergent feminism, and all are trying to articulate themselves in the light of huge promises of “democracy.” The constitution is rewritten during this period and the civil code is reformed for the first time since the 19th century, so there are really high stakes involved.

Biczel with scholar Andrea Giunta, artist Teresa Burga, curator Miguel A. López, and scholar Fiorella López at Burga’s home in Lima, April 2015. Photo: Courtesy Miguel A. López

CA: Absolutely. How did you decide on Latinx communities versus Polish communities?

DB: That’s a great question that requires some backstory. When I first went to Peru, I had the strangest feeling, because on some level Lima was the most foreign place that I’d ever been, even though I had been to and lived in many different places. At the same time, it felt familiar on a very subjective level. I thought I was insane to think that Lima was like Warsaw. However, when talking to [renowned contemporary Peruvian artist] Fernando Bryce, who had spent time in Berlin and Warsaw in the 1990s, he said that he had a similar experience.

Both cities are kind of ugly with their own very subdued charm, are aggressive yet closed off, and really rough around the edges. So I had this interesting subjective affinity for the place. Politically, Poland and Peru have much in common in the grand picture. In the 1980s, Poland was under martial law and Peru had a civil war, or, as it is officially known, an “internal armed conflict.” Both countries transitioned to neo-liberal economies and both returned to “democracy” at the same time. I am interested in these parallels and what we can learn from similar, shared experiences.

What can we learn from this? What are your hang-ups as an insider or outsider, depending on where you’re coming from? I did not feel at all authorized to write about Peru. I knew nothing about it, but my MA advisor, Rachel Weiss, asked “If you’re not going to do it, who will?” And I didn’t have an answer. Whether an insider, outsider, or researcher, none of the knowledge about a place is self-evident or inherent. One way or the other, you have to learn it.

For me as a researcher, the most important thing to do is develop a framework, ask about how the dominant narratives were created and who was not included in them, and why, so that I can reframe my research questions. I do think that being Polish helped me in Peru. In some cases, I worked with artists who had been imprisoned and persecuted during the Peruvian internal conflict, and I think that they trusted me more as a Pole rather than a U.S. American. It was easier to introduce myself and make connections.

Panel discussion in conjunction with the exhibition “Jacqueline Nova: Creación de la Tierra” at the Blaffer Museum of Art, fall 2019. From left to right: Daniel Castro Pantoja (curator), Bruno Ríos, Rachel Mohl, Nicholas De Genova, Biczel, Gabriel Martínez. Photo: Courtesy Daniel Castro Pantoja

CA: You’ve been doing this research for ten-plus years. When did you make the transition into nonprofit work?

DB: I’ve been working with nonprofits off and on for some time. I started working with nonprofits in the Midwest, where I lived in the 2000s. My interest in Latin America started there, too. For a Polish immigrant, my affinity with Latinx people was immediate because of the circumstances that have pushed our people to emigrate, and also our class status. I worked for a Latinx arts center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It was very much rooted in the heart of their neighborhood.

I came to writing and administrative work through art-making and working with colleagues who were art makers and art practitioners. I began writing through my interest in articulating a certain cultural scene. I’m very much a contemporary historian in the sense that my writing is closely tied to being in dialogue with practicing artists. Therefore, developing platforms is also interesting.

CA: This explains the shift to Houston Center for Photography (HCP).

DB: Specifically, with HCP, I was at The University of Houston (UH) for three years prior, as you know. I really enjoyed working at UH. The student body is incredibly diverse and incredibly talented, and I wanted to give recent graduates an opportunity to show. They deserve more opportunities in this city. They also deserve to draw some national attention. So the prospect of this institution serving Houston more, as its name suggests, was very enticing.

CA: Do you want to toot your own horn and speak about some of the things you accomplished this past year?

DB: Yes, I will toot it! We did a lot. We did a lot of deep internal work. We completely changed the governance structure of the organization, which is hard to do. HCP began as an artist-run, member-run organization. In theory, this worked until last year; however, given the scale of the enterprise, members were absolutely disengaged from the actual governance for many years. So this was an opportunity to change the bylaws to reflect that this organization is run by professional staff.

The pandemic had a huge, adverse impact on the organization. I had to hire a lot of new people in the course of a few months. But this was a great opportunity to think about HCP’s programs in a fresh way. When I hired Lou Benjamin to be the Education Director, we quickly realized together that it was time to think of education in a new way. Even mundane things like the systems we have in place to put classes online, register students, take payments, etc. — all the backend had to be updated. We completely redid the platform and Lou has also been working on a new curriculum design.

We also have all kinds of community programs, and in the wake of the pandemic we had to reestablish many partnerships and create new ones. Anne Houang, who began as our Access and Community Education Associate in February, has done amazing work in identifying new partnerships. So much so that we have worked with more individuals this past year than even before the pandemic. Anne is unbelievable and incredibly committed to community education.

CA: And you all received NEA funding?

DB: Yes, we got two major grants from the NEA! $50,000 from the special American Rescue Plan funding and a $35,000 Art Projects grant for exhibitions for next year.

CA: Let’s discuss the difficulties of nonprofit work. Should we talk about it?

DB: Let’s talk about it. Houston is a city that has changed tremendously. You and I both know this because we have lived and traveled back and forth for some time. And we know that when cities grow and expand quickly, the rising cost of living and working has a huge impact on you as an artist or culture worker. The reality is that it is more and more expensive to live and work here.

At the same time, the philanthropic world has not changed much. While we have BANF, which is much needed, there are no new institutional funders. Also, most of the funders are giving on the same level that they gave 10-15 years ago. So raising money is very difficult because the need is greater. And it becomes harder and harder to bridge the gap between the actual needs and resources available.

CA: On top of the city expanding and the cost of living rising, then you slap on a pandemic with inflation. I’ve seen in my own nonprofit work that funders were confused about why organizations needed more or were upset about a decrease in attendance, applications, proposals etc., and totally dismissed the fact that art is a luxury that many people could not think about. In Houston specifically, I’ve noticed that institutions have a problem with audiences. Their audience is changing, but they’re not changing their output. It’s the same 10-15 programs with the same 10-15 artists. Most of this is out of fear, and some of it is out of exclusion. Do we want a new audience or do we want to maintain the same audience we’ve built?

DB: Houston, per capita, has less nonprofit organizations than the other major cities. See Understanding Houston.

CA: It’s interesting how things always come back to money. It’s one thing to have a dysfunctional board or staff, which can be remedied. But without the proper funding, network and technology mean little to nothing.

DB: Yes, and there are some Texas-specific things. Despite all the titanic work that Texans for the Arts is doing, our state funding is puny. And our city funding, although it might seem generous, is highly problematic as it is tied to hotel occupancy tax. Obviously, it was deeply affected by the pandemic and it will always fluctuate. One of the contentious issues with the City of Houston is the appropriation of APR funds that the city received for culture. Austin voted to appropriate some of that money for arts and culture, and Houston has not done this despite all of the advocacy efforts. It still can, but it has not been guaranteed yet.

From when I was doing my Masters in Chicago, I remember this very striking statement from a Cultural Policy Scholar named George Yudice. He said, “The fact that the U.S. is one of the few nations in the world with no cultural policy, is precisely the U.S’s cultural policy.” Though I had always understood this, I had never felt what it meant until this last year.

From left to right: Harold Urteaga, Kaila Bagadion, Kristina Brosig, Lou Benjamin, Anne Houang, Theresa Marshall, Krishna Roberts

CA: Absolutely. We do not have a director of cultural policies of any kind at the governmental level. The U.S.’s cultural policy is directly tied to philanthropy and large corporations. I also found this out very recently.

DB: And that says it all. It’s not as if there is a perfect model for this. There are very real dangers when cultural policy is too closely tied to the nation-state. Poland is a great, sad, example. In the last few years, the Minister of Culture has systematically gutted most of the arts institutions, revoked a slew of directors, and replaced them with ideologically correct apparatchiks. Neither extreme works.

Biczel with artist Jake Eshelman during the walkthrough of his exhibition “Cherish the Clear Skies! Vitality in a Ukrainian Village” (April 8–June 19, 2022) at the Houston Center for Photography. Photo: Anne Houang

CA: So, after a mighty year at HCP, you’re going back to academia with a Postdoctoral appointment at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Will this be a continuation of what you’ve been working on?

DB: Yes. The main goal now is to finish my book and get it published. I am 80% complete.

Honestly, one of my biggest fears this past year was that I would never write anything again but a grant application, and that did not feel good.

CA: Oh yeah, work will do that to you. I think about that all the time. So perhaps we can close out with a question that I think both of us can answer. How do you balance your creative and teaching practice with the practical work of paying the bills?

DB: This is a great question, but a difficult one. First, it is disheartening to see how much knowledge production is dis-merited in the United States. Writing never fully pays for itself. It is why you teach or have nonprofit gigs. Institutions in the so-called “third world” are willing to pay more for writing than some of the more prominent institutions in the United States. It is disheartening and tells how much knowledge is not valued.

CA: When people have asked me that question before, my first answer is that it comes down to tight time management. But the truth of the matter is that there is no balance and this is its own problem. We don’t value creativity or intellect. It is always interesting to find an employer that respects your time. I’ve had a number of jobs where I had to maintain a boundary about my time, and that contributed to the end of those positions. I knew if I negotiated my boundary, they would push the limits every time.

DB: Do you know Oliver Burkeman? Check out the book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. He basically tells us that it is humanly impossible to do everything. The most you can do is choose what is important to you because the “to-do” list will always be infinite. And this is a crucial reminder that goes against the grain of all the “productivity” advice. We have a finite amount of time on this earth and we have to choose what matters most to us.

The other thing that I learned is that there is no dollar amount you can put on your time. Your time is priceless. If you are not doing the things that are meaningful to you, there is no way to compensate for that.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.