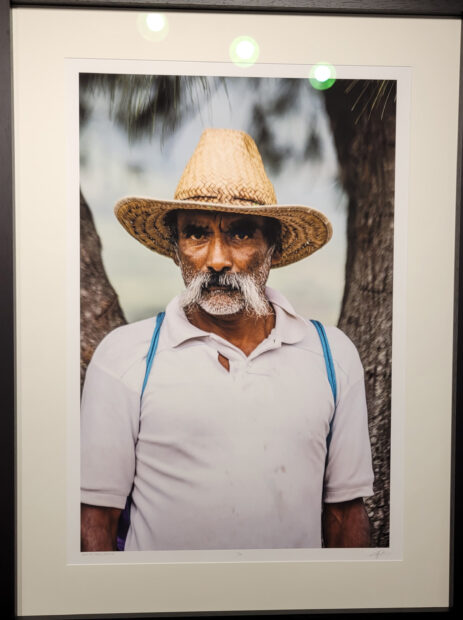

Greg Davis, “El Orgullo de Juxtlahuaca,” 2019, Santiago Juxtlahuaca, Mixteca, archival museum canvas pigment print.

The Art Center Waco serves as the debut venue for Greg Davis’ photographic project Oaxacan Gold: Illuminating Mystical Mexico. With vivid, large-scale images, Davis, a contributing photographer to National Geographic, sought to transport viewers into the heart of the spiritual and communal events he experienced in Oaxaca, Mexico.

When an artist sets out to document communities of which they are not a member, particularly communities of color, they risk evoking a time-worn ethnographic feel. One example of this possibility is Davis’ 2018 archival museum rag pigment print Sol de Vega, an intimately close view of an older Oaxacan man framed by trees. At first glance, the image calls to mind anthropological portraits in an ethnographic display. The subject wears a white polo shirt, its age indicated by brown stains and a tear near the collar, while a woven straw hat protects his face from the harsh sun. The context of the image is difficult to deduce. The man’s rumpled collar and what appear to be the bright blue straps of a drawstring sack slung around his shoulder suggest a level of informality, that he was engaged in another activity before he stopped to pose for this photograph. That the piece’s title refers only to the region in which the photo was captured, rather than the name of its subject, suggests that an individual can serve as a representative type for a place.

Yet, there is an alternate reading of this portrait. The man intensely stares straight into the camera, creating a dynamism that moves through the image straight to the viewer. Because of this direct connection bypassing the photographer, Sola de Vega avoids the passive consumption and lack of agency associated with historical ethnographic images.

Although individual portraits are sprinkled throughout the exhibition, one of the central themes in Oaxacan Gold: Illuminating Mystical Mexico is religious festivals. Davis documented celebrations of communities that sustained cultural values through generations following colonization. In a black and white image titled El Orgullo de Juxtlahuaca, viewers are confronted with a procession. A group of costumed people, predominantly men, approach in long-haired chaps, blazers, and bandanas capped off with devil masks. The figures are rendered more intimidating by Davis’ choice to capture the image from a crouched vantage point, from in front of the lead figure’s legs as his body extends forward in stride. The man in front is flanked by two others, who also press forward in full costume, while peripheral figures engage the crowd, presumably just out of frame. This parade of figures dressed as devils is derived from a Catholic story of triumph over the Moors, an occupying power in Spain for more than 700 years.

To enhance the experiential quality of the exhibition, Davis acquired artisan works during his travels through Oaxaca to complement his photographs. The display of art in this manner is not novel in an exhibition focused on documenting communities abroad. However, the artisan works are thoughtfully handled, labeled with the name of each artist and a QR code linking to the artisan’s social media page, where works can be purchased directly from them. For example, facing El Orgullo de Juxtlahuaca, a viewer is confronted with devil masks carved by Alejandro Vero Guzmán, a renowned mask sculptor. Far too often, folk art has been divorced from its original context, and its makers have been denied acknowledgement as artists. This inclusion of folk artists indicates Davis’ alignment with efforts to decolonize what have long been traditional methods of display.

While Davis’ project aims to highlight the particularities of Oaxaca, his section on the Dance of the Devils beautifully captures the complicated legacy of colonization. The continued celebration of this festival refashions Spain’s resistance to colonization as Mexico’s own resistance to Spain, illustrating the complexities of post-colonial identification. Further, festival’s inclusion of masks illustrates the influence of African heritage in Mexico, which still lacks acknowledgement. In the colonial era, Spanish cultural traditions were foregrounded, while Indigenous and African customs were suppressed and appropriated. Efforts are being taken to reclaim the cultural roots of practices like the wearing of masks, but there is work to be done in post-colonial communities still grappling with embedded White supremacy. This body of work sparks many rich areas of conversation on the legacies of colonialism, on histories passed down, and whose stories are represented.

Greg Davis, “Los Colores de Oaxaca,” 2018, Sola de Vega, Sierra Sur, archival museum rag pigment print.

One tradition that should feel familiar to many in the United States is the Day of the Dead, given the Mexican holiday’s inclusion in mainstream popular culture. Davis provides striking images of Oaxacan Day of the Dead celebrations, however he clearly intends to illuminate other, less widely known festivals that bring Oaxacan communities together.

Los Colores de Oaxaca thrusts viewers into a parade for the Feather Dance. In this image, Davis capitalizes on the color that makes these festivals so vibrant. In the foreground, two women dance across the image, one in a bright blue dress, and the other in a yellow floral dress that captures the energy of the moment as she fans her skirt upward in front of her. Behind them, men in large feathered headdresses move forward in a line, clearing the way for the next rows of dancers and musicians that fill the background. Warmth emanates from this image as the woman at center soaks in the celebration and flashes a confident smile to parade goers just beyond the camera.

Ultimately, Davis introduces viewers to traditions and stories that might be new to them. Considering the diversity found in Waco, and Texas more broadly, a more important issue to consider is how diverse audiences connect with this exhibition. Exhibitions can be an effective tool for arts organizations and museums to amplify representation of people of color, but shows alone cannot eliminate barriers that have persistently disconnected visitors from these institutions. Also, this disconnection can be exacerbated if communities of color see others improperly telling their stories.

Davis’ exhibition thoughtfully negotiates this delicate balance. His carefully selected vantage points, rich colors, and balanced compositions compel viewers to engage with those represented in a meaningful way. The distanced, objective gaze that could make a project like this problematic is eliminated. Instead, Davis invites viewers to immerse themselves in the spectacular events of Oaxaca.

Oaxacan Gold: Illuminating Mystical Mexico is on view through August 13, 2022 at Art Center Waco.