Brian Ellison is an artist based out of the Third Ward in Houston, whose work spans across photography, moving images, performance, and installation. Over the past several years, he has shaped his practice within the fabric of the community in the Third Ward, more recently in his continuing work with Project Row Houses. Ellison’s work encompasses celebrating, grieving, healing, and being soft, as a community. Working collectively, he opens himself up to welcome others into his journey of recovering from various forms of historically based social violence that are emotionally shouldered by Black folks. His process makes possible vulnerability in safe spaces as a starting point for healing and self-affirmation. Ellison’s work is a part of the community building by artists and curators working out of the Third Ward, like Jessie Lott, Rick Lowe, Ryan Dennis (who is now based out of Mississippi Museum of Art), and Dr. Alvia Wardlaw — and the ever-present legacy of Dr. John Biggers and Texas Southern University. Ellison absorbs, documents, shares, and manifests the ethos of connectivity and balance at the heart of Houston’s art scene.

Liz Kim (LK): Let’s start with your first major film project, UnMASKulinity. Could you tell me about the circumstances that brought it together?

Brian Ellison (BE): At the time, I had been wanting to do a documentary exploring vulnerability and toxic masculinity, or what we know ‘Masculinity.’ I wanted to ask, “Who told us what it’s supposed to be in Black men and Black boys?”

I pitched that idea to the Idea Fund, and I was awarded funds to make it a real project. I interviewed probably about 30 to 40 men and young boys. There were a lot of interviews, a lot of discussions, and a lot of montages, as ways to think about softness. What I picked up in the interviews was that this was the first time that probably 95% of those men had ever had questions around what it meant to be soft, or what it meant to be a man when asked them. I asked things like, “What are some things that were handed down to you that you do that you feel don’t serve you anymore as a man, as a father, as a grandfather?”

It really dissected the culture of Black masculinity in a way that was very new for me. There was a lot of unraveling, a lot of tears being shed, and a lot of people sifting through their trauma that they didn’t know was trauma. But there was also a lot of happiness, a lot of remembering, a lot of talks about their fathers or father figures, or lack thereof.

The expiration date for Black boys being able to be Black boys is super early. They can only be a Black boy for a certain amount of time. UnMASKulinity spoke about how that is not reflected in other societies, and how messed up that is. They should be able to explore Black boyhood, embrace it, and have fun in it, and not feel like they have a target on their back at the age of 14. They should still be able to be just boys. But those conversations really made me realize that’s not the reality. I mean, I know that for myself, but that’s also not the reality that they had for themselves and for their sons.

LK: Yeah, I recall Trayvon Martin.

BE: I mean, we have example after example, right? There’s a lot of fear for fathers when talking about their daughters and their sons. After about six months of filming, we did a huge showcase at the MATCH in midtown Houston to a pretty packed house.

We pre-sold tickets, and I couldn’t believe the number of people that came out, and the amount of people that the film touched. I feel like it was a success for somebody who never really filmed anything before. I gave myself permission to mess up and just tell the story anyway. Don’t wait for it to be perfect, or the idea of whatever you think perfect is.

That led me to another grant, the John Kelly Foundation Grant, an award of $50,000. From that, The Black Man Project was born. I asked two of my collaborators to be a part of this with me, because this is not a project that I envision traveling by myself. I’m not a hoarder in that way.

I have amazing friends who I have these discussions with. Anthony Suber is a sculptor, and Marlon Hall is an anthropologist and a yogi. What does it look like to take the conversation that we had as brothers to other spaces, and curate a space for healing, listening, learning? We wanted a really transformative, a real safe place, a space of no judgment with food and drinks.

It was a transformative experience. We traveled to major cities all over the nation. We partnered with Google in Seattle. We partnered with a university in Maryland, we went to Atlanta and New York. We went to Los Angeles and partnered with a local barbershop and we also did it here in Houston.

LK: You refer to the manifestations of The Black Man Project as healing installations. Could you talk about the format and the activation of the project?

BE: The format was based on a conversations that myself, Marlon, and Anthony had about what it would look like to curate a dinner, expanding to a salon experience. It’s curated with questions. When each person comes in, they are handed an invitation or a welcome layout that asks a series of different questions. All these questions we discuss openly with each other.

Most people come in with this huge emotional wall, and the event makes the wall just completely come down. Because, we realized, no matter the kind of career you have or where you’ve been or what you’ve done, we all have this common thread in this experience. We all carry it. And we’re not talking about it publicly. Just this great unraveling of these things that we need to get out of us via conversation collectively.

Brian Ellison, “The Black Man Project,” 2018-present, photographic documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Brian Ellison.

There’s something about a collective conversation, of being heard, being seen, and being felt, that allows each person — each man that’s in these conversations — to leave feeling hopeful again, to know that they’re not the only ones to know that something like this exists. Also to know that we are available and accessible today.

LK: What were some of the questions?

BE: As a part of the experience, we would have them create a four-word story. What four-word story would you tell your future self? What words can you give your inner boy now that you know he needed in the past? What are you dealing with? What did you come here with today that you don’t want to leave with? What can you leave here once you leave, and give yourself permission to do that?

We also partnered with the CAMH, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. We did the activation with DiverseWorks in Houston too. We partnered with the community and we created this healing installation as part of The Black Man Project. The opportunity came down by way of DiverseWorks — Marlon was doing something yoga-related with the CAMH, and we decided to connect these two worlds. It was beautiful.

LK: Could you then tell me more about the installation at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston?

BE: Yes, it was called Project Freeway. Basically we created a three-step series of the past, the present, and the future. It was a journey about healing and conversation with yourself.

In the section on ‘the past,’ you get partnered with another man and you walk through these three big frames. You will say something to your past self that you know your past self needs, and then you look at your partner, say it to your partner, then say it to yourself again.

Then you repeat the same routine with your present self and with your partner.

Finally, you move on to your future self. You sit in a chair and look at a mirror and you then affirm your future self with everything you have said. It seems so very simple, but it was very, very emotional.

Brian Ellison, “The Black Man Project,” 2018-present, photographic documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Brian Ellison.

We had about 15 or 20 men in there, and this was right after COVID. So we had the doors open and it was very restrictive. But it really turned into what we knew it would turn into. We wondered how we had managed so long without these types of spaces, but all it takes is someone to just open the door and give a title to something.

LK: This simple act becomes so transformative just by creating a space around it.

BE: At each frame there was a mirror at the bottom, so you also see yourself as you step through the frame, looking down, and your partner has to help you get up every time. As you step through, you look at yourself. The point of having a partner is that you know you’re never alone, and somebody is always there you can reach out to.

Brian Ellison, “The Black Man Project,” 2018-present, photographic documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Brian Ellison.

Oftentimes, Black men navigate the world like they’re the only one going through it, like nobody cares. Which is why the suicide rate for Black men is high. And honestly, before UnMASKulinity, before The Black Man Project, I wanted to end my life. I was on the brink. And I don’t share that with shame anymore, because I am still here. Before UnMASKulinity, and before The Black Man Project, I thought my internal demons and depression was normal. I thought trauma was normal. None of that was normal, and I was not feeling okay. People were telling me I was okay, but I wasn’t.

That was my life, and that is my life. I got a semicolon tattoo on my wrist because of what a semicolon means: in a place where something could’ve ended, it began again. I have it permanently on my wrist as a reminder.

I mean, these expectations and ideas about what it means to be a man, they just kill people.

LK: There’s the flip side as well, the gender-based expectations put on women by society, and that’s also what you talk about in your film, UnMASKulinity. About people being unable to access that space.

BE: Yeah, when do you lose the ‘hu-‘ in the man? Human. Few people have access to all their emotions and many need some help. I was talking to my friend yesterday, and I said, “Man, I love you.” He said, “Don’t tell me that, my mama don’t even tell me ‘I love you.’” I was like, “Man, this is who I am bro, I love you.” He then said, “My Mama only told me she loved me one time.” And I was like, “Oh, I’m sorry. I’m sorry but I love you.” It is right, to be loved and to be able to express that and yourself.

LK: In UnMASKulinity, you end the film by having people turn around in a chair, and then, literally, give a transforming smile.

BE: You know, it’s a process of transformation. It comes from openness and being in touch with your feelings, and just being able to open up the wound.

Another part of The Black Man Project and UnMASKulinity is pushing therapy. Most men are not afraid because they think they’re too tough, but there’s actually a levee that’s waiting to break. These men know they need to talk about themselves, but that’s a thing they refuse to do. I want to try to take that stigma away. What does it look like when that doesn’t exist?

LK: I love that openness, and just being in touch with your memories, your feelings, and being honest about how you feel.

BE: Most of the men that I talked to said that their dad would open up and start being expressive when they were pretty much near death. There’s something about mortality — that’s when people would get the apologies they wanted. People would tell me there was some reflection happening towards the end of life.

LK: Yeah, everybody goes through it in a different way, but there have to be better mechanisms in our society that allow for that kind of space to open up. I really love that that’s become your focus, creating those spaces for dialogue.

BE: I think we should acknowledge tenderness in everybody. We are fragile people. If you watch Bambi and cry, cry! You know? Who doesn’t cry?

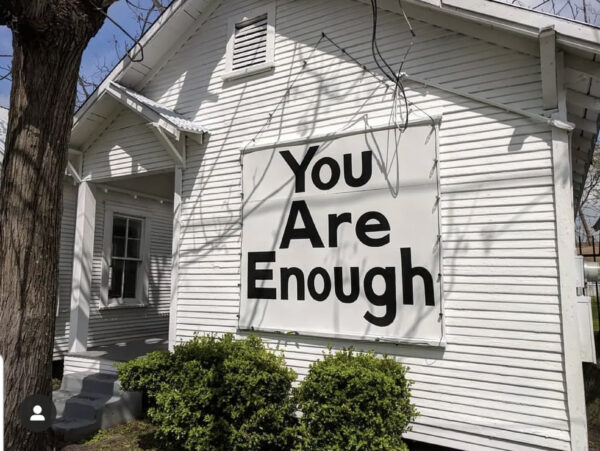

LK: Can you tell me about the You Are Enough Project? How does that also deal with some of the themes that you’ve been talking about?

BE: That was my first cry out after my suicidal space. I just spray painted “You Are Enough” on the side of a building. It was a message to myself and to a Third Ward community that has been heavily gentrified. And the crazy thing is, that spray paint stayed there for years. People would take pictures in front of it, and they hashtagged #youareenough.

It turned into a movement.

So that’s when we activated the block. People need to know that they are enough. It turned into a block party of healing, filling conversations, and healing rituals.

We had three stations. At the first station, people had to acknowledge and write down what they no longer wanted to be associated with, or things they did not want associated with them anymore, on a piece of paper and put it inside a jar. At the next station, they affirmed themselves: they had to look at themselves and write an affirming, nice thing about themselves, which is so hard for many people to do. How do you affirm yourself? What are you? Are you beautiful? Smart? Then, you had to write a message to your future self at the last station. This was the most emotional step, like burning sage for a cleansing. It was like…magic.

I honestly haven’t even thought about this common “past, present, future” thread in my work until talking with you about it, Liz.

People who just lived in the area came. People I know who are homeless, and drink everyday. Also, educators. It was a group of so many different bodies. They all needed the same thing; no matter where you are in terms of society or class, you still need to know these things, right?

LK: That’s true. A significant personal change will transform you — dealing with your existence, the idea that you still exist in the world.

BE: It just could exist, as you are.

LK: Yeah, when you go through that really, really tough process…I mean, I also have depression.

BE: Thank you for telling me that, I appreciate that. I have depression, and we give permission to just say “I’m struggling with this,” and say it out loud. That’s reassuring, and lets people say “oh, it’s not just me.”

LK: I also love how you are activating spaces with words.

BE: We just wanted to give people a space to speak.

LK: Could you tell me about Round 47 at Project Row Houses, how the You Are Enough Project morphed into You Are Enough Still, and a short film?

BE: First it was the affirmations that I was receiving from the community and through the first installation, the block activation. Later at Project Row Houses it had community therapy and sticky notes. There were probably over 200 sticky notes from people, filled with affirmations to themselves. There was also a collage of photos of people in the neighborhood. I was speaking to the neighborhood when I said “You are enough still.”

Third Ward has given birth to me as an artist. I love Third Ward. I’m not from here — I’m from Tulsa, Oklahoma. But this me as an artist was born in the Third Ward. I used to just sit in my now-studio with Robert Hodge, and Jamal Cyrus was there at one point in time. So many different people, like Robert Pruitt, Lovie Olivia, and Delita Martin have poured into me in some way, shape, or form. Ryan Dennis saw me, and she gave me an opportunity. So the house was like a love letter to the Third Ward, with pictures, people, and affirmations.

The film A Day in the Tr3 looked at how people speak about a space they only hear about, and how that changes and how they think differently once they actually go. It’s about beauty — a lot of my work is about the beauty that hides in plain sight. A Day in the Tr3 highlights that. It’s a young man’s journey through his rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. But he’s also holding on to the very real things that are still there.

LK: After your installation You Are Enough Still at Project Row Houses, you also started developing a performance practice. Your first major performance piece is Black Heavy. Could you tell me about it?

BE: I’ll first give love to Jefferson Pinder for being super influential. This is for my practice, not in particular with Black Heavy. He has helped to reimagine what art looks like for me and in my mind by being a part of DiverseWorks, and being part of that with him allowed me to re-evaluate my own practice.

Black Heavy dives into the heaviness that Black people carry and that they can’t really acknowledge, because nobody cares. But the weight is still present, and it’s still real. It makes me think about Black athletes. Why do they jump so high? So fast? I think about it like this: if there’s a planet where the gravity is 100-times stronger than it is on Earth, I imagine that my navigation here on this Earth is like that other planet. What happens to my bones: do they get stronger and more dense? Because I’m so used to navigating with this weight. I can carry these loads. I can do these things only because I’ve become accustomed to it, but that doesn’t make it right, and it doesn’t make it okay.

Black Heavy dives into the heaviness of showing up to a place and having to pretend like everything is okay when it’s not. “Heavy” is any conversation I’ve ever had with a Black woman or a Black man on what it is like working in a workspace that looks nothing like them, doesn’t acknowledge them, and doesn’t acknowledge what’s happening in the media. You know, when George Zimmerman gets off, and you go to school as an educator the next day, and people are smiling. And you feel like it rips your guts out. And you gotta show up and teach anyway.

That’s Black Heavy. Nobody acknowledges that for you, and you don’t dare talk about it because then you’re disruptive, or you’re trying to access your emotions as a Black person in a white space. Black Heavy is leaning into that.

When white women cry, the world stops. Black women cry, who cares? If a Black man cries, you might need the police, I don’t know. It’s just diving into this irrational, uneven society that we live in where we just keep saying “they can do it, they can do it.” This is especially true for Black women, who are so much stronger, so they aren’t offered the same opportunity to assert their needs and values. Then when someone does, they are immediately stereotyped.

Like, “oh, don’t let me say anything, then I’m the angry Black man,” and so Black Heavy talks about the teeter-totter, this seesaw, where I gotta be right there in the middle. As a big Black man of 6’2″ and 180 pounds, I have to bring the octaves of my voice up to make other people feel comfortable, which I don’t do anymore because I realized when I did, I was performing.

Black Heavy is me acting out the performance that I did for half of my life in moments of questions. For example: how’re you going to get a good job? You gotta make people feel comfortable with your existence in the room, only to then realize, that ain’t my problem. You’re not comfortable with me? That means something’s wrong with you. Right? Black Heavy is all of that.

It’s also my grandmother, my great aunts, and the things that they normalized because they had to. All this, and the angry, frustrated tears we shed without a true outlet.

You were talking on the phone about your relationship with Black women and how they’ve always shown you love, they’ve looked out for you, like being mentors. That’s how I know them to be with anyone. You know?

LK: They care, they really do care.

BE: It’s a different type of tenderness.

LK: It really is. You also recently had a show at Art League Houston titled Backbone. It was a major show for you; can you tell me about it?

BE: I was raised by my great aunts and my grandmother, who died ten years ago. Old Black women are a backbone for me. I figured out it was a mourning and a celebration of my grandmother and every other Black grandmother I’ve ever had, because I’ve had many.

I know that the elder Black women are the backbone to the Black community. Nothing moves without them. They’re the caretakers, the strength, the softness, the love, the visionaries, the safe space, and the advice givers. I’m nothing without them. Backbone paid homage to that.

The first gallery I had ever seen in my life was the living room space in my great-grandmother’s house. Nobody could sit in it; it had plastic on the couch, and you best not be sitting. I didn’t know it was a gallery, I just knew you did not sit in there. There’s a poem by Zora Neale Hurstonbn, called “How it Feels to be Colored Me,” that talks about the first gallery she ever saw, which was her porch as she watched the interaction of people, day in and day out. It’s like the process of doing Backbone, and I cried a lot.

You know, I still haven’t visited my grandmother’s grave. I want to. I just want her to be proud, and I want her and my great aunts to know how much they matter and how much I love and appreciate them, and how valuable they are. Oftentimes elders feel invisible. I wanted to create a space of permanent celebration.

Backbone is a celebration of all the beautiful things you could think of in Black grandmothers.

LK: You have objects in the show that remember your grandmother as well.

BE: Yes, the preservatives in jars. My great-grandmother passed away and those preservatives outlived her, and those are things I remember.

She grew up in a different time. She experienced the Great Depression, with a mindset that if something were to ever happen, we have things that will help us survive. I’ve seen her hit a possum over the head and cook it. You’re not gonna waste that — it was, just…different. And how do I carry that? How do I honor that? It’s also a sense of not being wasteful, and foresight.

LK: Survival, yeah. They carry their families through the tough times.

BE: It’s so deep. Preservatives are our legacy. It is a different type of love our grandmothers give. You can smell it. You can touch, you feel it.

LK: Could you also tell me about your recent show It’s Hard Being Hard: Journey to Softness, A Work in Progress, which took place at the Elgin Street Studios in Houston?

BE: You know when you ship something in the mail, and you put bubble wrap on it, and they ask what this value is? This piece was about the value of my body. The need to want to be handled with care, to be delicate. Can I be delicate? Can I be treated as such? How do you handle something this fragile? Can you imagine me being fragile? To be seen, beyond what the TV screen tells you.

Brian Ellison, “Hard Being Hard: Journey to Softness, A Work in Progress,” 2022. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Brian Ellison.

What happens if you touch me for yourself? What happens if you experience me for yourself? What happens if you know who I am? So much of the ideas about something, and someone, are based on things that we haven’t actually experienced. People look at me, and they assume that I’m something I am not, but really…I’m delicate…I’m a flower out here.

I covered the entire floor in bubble wrap and put up three images of Black men, and put bubble wrap on top of them. People didn’t want to walk through the space, because they would think, “can I walk on those?” And I sat in the center. I just wanted to be handled with care, and I wanted to explore that.

LK: So what’s next for you?

BE: Backbone will be showing at Lone Star, so that’s going to turn into a traveling installation. I’m excited about that. I’m working on a show that deals with Black preservation, and what that looks like, to preserve Blackness and Black things. I’m also exploring the education system. How the education system, K-12, exploits and propels Black kids in schools into the prison pipeline. Diving a little bit deeper into the stats of what that looks like.

The Black Man Project also got a BIPOC grant, so we’re starting a podcast and doing some community installations, and community workshops with fathers and dads — Black men — through group therapy sessions. We’re also establishing partnerships to create access for men to have therapy sessions. That’s happening now.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.