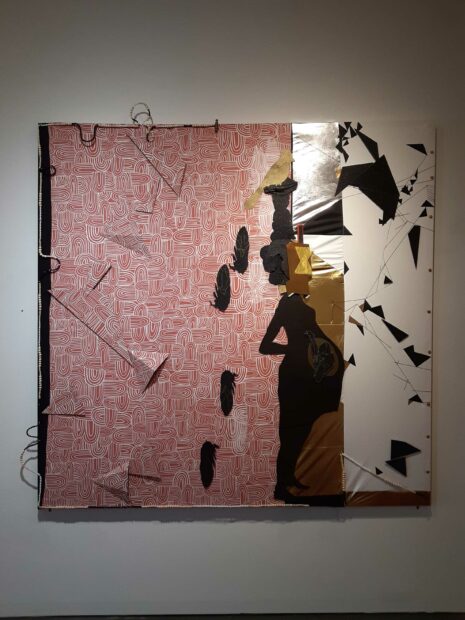

Anthony Suber, “Summer Cicadas,” 2022, mixed media on fabric, 72 x 72 inches. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Visiting Anthony Suber’s exhibition is like being transported to another planet, or dimension. His vision is so acute and unlike any other aesthetic I’ve encountered in my career. The core concept that drives his work is history — the history of the African diaspora, as well as the deeper histories shared among ancient worlds since the neolithic era, manifest in what he calls “sacred geometry.” His work also speaks to East Texas, between Palestine and Crockett, through personal details of growing up. There are allusions to the gardens of his grandmother on his mother’s side; local crafts appear in forms of quilt and pottery; and an explicit reference in the ruddy red earth that forms the tonal basis for a lot of his work.

Historical Black artists like Charles White and John T. Biggers have given him the visual vocabulary to bring the complexity of his roots together, particularly in their use of patterns in the representation of diasporic and West African visual cultures. Thematically, the show takes the viewer through a timeless lifecycle of birth, growth, love, adulthood, death, and back, through Suber’s unique visual language of piecing together intricate parts into a whole, whether in his fabric-based collages or his mixed-media sculptures. These works distinguish themselves in their mathematical precision and delicacy, as well as through sense of a living surface.

The first piece in the exhibition, titled Summer Cicadas, represents incubation and potential. It is a large canvas that has been sewn together with rust-patterned, silver, black, white, and gold fabrics, which were then stretched onto a frame. In the center-right of the canvas stands a silhouette of a pregnant woman made of a black felt cutout fixed onto a foam board. Running adjacent to the pregnant woman are outlines of cicadas, symbolizing renewal and change, made of sparkling black paper with wings drawn in gold pen. On her head, the woman wears a brown and rust-tone mask that is folded like origami, with another see-thru mask superimposed over it in gold, and held together roughly with threads.

All of Suber’s figures wear masks, and behind each are people that all of us know from our own histories. The figure’s hair is a tall tower cut from thick, iridescent paper, on which sits an outline of a cardinal, cut out from black fabric and decorated with a flattened geometric pattern. Cardinals represent the greetings of our ancestors, and Suber emphasizes the connection between the past and the future by having the figure’s womb represented by a cut out of the same fabric material as the bird. Inside the womb, we find an adult human outline with a brown bag over their head, curled in a fetal position. This figure is simultaneously the past, the present, and the future. The work is about potential — a “latent” energy of the universe that Suber refers to — and the immense energy that history has in store, which informs the present and shapes the future of the world.

Characteristic of Suber’s work, the composition is coiled thick with energy, and various parts move as our eyes travel across the work’s surface. Pieces of paper in various sizes have been glued onto foam board then cut into triangles which are strewn about on the surface. Delicate shapes stack and fall on the white part of the canvas, with black thread sewn in linear patterns and forming a semblance of triangles. They are flying geometry, and they feel like they are falling, dripping from above. Surrounding three fourths of the edge of the frame are beads strung together on wires — they occasionally bend like hills, jutting in and outward from an otherwise straight framing outline. The beady borders seem to be trying to contain the u-shaped arcs in the printed pattern, the bursting neurosis of the repeated shapes in earthen red tone, like the uneven and habitual texture of the day-to-day. Details, details, details — each adding a layer upon layer of visual tone, which altogether vibrate in a busy frequency.

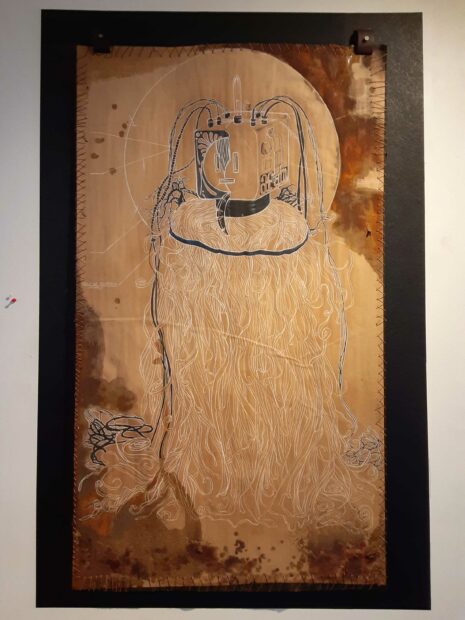

Anthony Suber, “Griot Gospel Mask No. 3,” 2016, mixed media, 61 x 35 inches. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Nearby is one of Suber’s earliest pieces from 2016, Griot Gospel Mask No. 3, a drawing on rough, brown composite paper, like the kind that makes up paper bags. This drawing, and the adjacent two others in the series, were the road map for Suber’s subsequent works, and in this way, represents birth. There are touches of resin at the corners of the piece, with heavier application at the bottom of the work, as though Suber was sealing this moment for posterity. A figure stands in three-quarters view, drawn in white pastel with black highlights — they are covered in a waterfall of lengthy paper strip cutouts in twisted curls. You can practically hear the rustling of the paper; it’s as if you can imagine the sound of the figure moving, like wind through trees. There is a sense of something ancient, yet also digital and mechanical, as the head is a plug outlet, with holes functioning as a face. Loose wires fall from the outlet like braids, and long coils curled up on either side of the head. An unspoolable tangle of a black, wiry mess peeks out from the back over either of the figure’s shoulders, like insignia. The figure looks both organic and man-made. Pointing to the mouth, an underlined caption reads “ancestral recitation portal,” like a biological textbook diagram. Other caption lines remain empty. The figure is still, yet full of a potential for energy, which has been compressed into them through the repetition of the artist’s marks. According to Suber, the drawing is about what modern life and identity feel like as a Black man, particularly within the disjunctions created by expectations imposed by society. A ritual, a diagram, and an incantation, it reads like a blueprint for survival and for healing.

Anthony Suber, “Unmaskulinity Mask, Huey,” 2019, mixed media, 16 x 8 inches. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Further along the same wall is a mask signifying the next step, in Suber’s process: taking on a social identity. The main framing piece is a solid black felt cover which is folded lengthwise five times to curl it around the contours of a face. Rising from the top of the mask are two raw MDF pieces, cut and stacked over each other like a crown, sculpting the figure’s accomplishments and titles. The top piece has drawings of linear triangular patterns which are cross-hatched into squares, like text. Both pieces are folded slightly inward, like a book, with gold buttons and round metal cutouts unevenly placed along either side.

Round, black marble-like beads are strung along a thick curved wire, protruding at the temples of the main frame like the bill of a cap. At the center tip of the bill hangs a wire mesh ring in gold, an accent that calls for attention, a demarcation. The row of beads signifies a personal boundary, an awareness of one’s surroundings. At the bottom of the mask, a faux leather brown handle hangs like an open mouth, attached to the main frame with screws. A composite throw or rug cut into a near-triangle shape hangs down from the black frame like jaws and a chin in off-white, with silver buttons punched on either side. The mask seems to have its mouth open to speak from a position of authority, which is another component of being social: to be heard. Altogether, the object is a mask of distinction in bold forms, sharp angles, and round punches, where even organic surfaces of the woven fabric feel hard. This outer shell is what one wears to be recognized by society.

Anthony Suber, “Mother Afmerika,” 2017, mixed media, 30 x 108 inches. each. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Across from the mask stands a tall sculpture titled Mother Afmerika, which represents a recognition of another being as a part of one’s life, a significant other. It is made of wood and concrete, and divided into six vertically stacked levels. Around the periphery of the base sits shimmering black sand, from which three white face casts protrude, as if they are emerging, or perhaps sinking. Who is this new person? The process of finding out the answer is intense, as signified by the base of the sculpture in octagonal wood, brushed and charred at its corners by fire. The rest of the sculpture is made of many horizontal layers stacked on top of one another. Concrete pieces in the stack are molded into geometric trapezoidal blocks with bronze colored shapes painted onto the surface. Between some of the blocks are separators; some are flat concrete trays, and some are wood blocks — thin MDF pieces in multiple tones glued together, then cut into an octagonal shape, mirroring the base. The sculpture is about compressed and compacted energy, like a loaded spring, a relationship that went through stacks upon stacks of trials and tribulations. A head with rusty metal rods as hair sits at the very top, made of stacked and glued wood sheets cut that reveal artificial rings, with their center carved out for an embedded face cast. This cast, which has its eyes closed, is painted gold and wears a nose ring made of the same gold mesh ring as from the mask. It is a confirmation: they are kin!

Anthony Suber, “What Was Seen,” 2022, mixed media on fabric, 18 x 18 inches. each. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Inside an embroidery ring, thick white paper cutouts of organic shapes hang like clouds, with the same linear triangle patterns drawn in pen throughout. In What Was Seen, at the right side of the composition is a cutout of a crouching silhouetted figure painted in a rust color, wearing a mask like a blank tablet or computer monitor. This figure sits in thought, processing a trauma, which is alluded to through the jaggedness of the work. The base fabric for the composition is a black, tight houndstooth pattern, a grinding metaphorical mesh of modern day-to-day. The triangular cutouts of shimmery black paper, mixed with tan faux leather triangles, are strewn around the bottom curve of the ring frame, as though something has shattered in this clouded space. There seems to be an effort to round out these edges, as there is a layer of this faux leather cut into a ring pattern, and peeking through the cutouts is a bluish fabric with gold floral patterns. This combination represents wheeling through history as a means to enact a healing process. Between the contrast of the shattering and healing motifs, the latent movement strewn about in the piece’s layers is ballooning outward, as if inside a portal, and the loop works to contain the stretch of their compounded energy. The work attempts to bear out the unbearable.

Anthony Suber, “From the Field, They Carried Him,” 2022, mixed media on fabric, 46 x 46 inches each. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Eventually, after the accumulation of difficult as well as rewarding experiences in life, we face death. In From the Field, They Carried Him, a large ring cut from MDF forms the frame of this key piece in the show. The frame is adorned intermittently with circular disks in darker wood tones, like submarine windows. Gray fabric with small black polka dots is the canvas for this collage, and a round cutout of the gold fabric with blue floral patterns is placed at the center, like a celestial object. A ring of wired beads surrounds the periphery of the frame. Cardinals appear again, representing the dialogue with our ancestors that ensures a continued connection to those who have passed; the birds’ paper cutout silhouettes in burnt orange are gathered in a thick arc around the top of the composition. In between these birds and the cradle of the lower frame, a black silhouetted figure is both falling and simultaneously ascending, with arms outstretched like a bird in flight. Three smaller white silhouettes are layered above the figure, and at the top, they eventually transform into brown silhouettes of cardinals with black faces and yellow beaks. These smaller, more delicate cutouts of cardinals encircle the top curve of the golden sun, in the middle of the composition. The figure wears a mask cut into a shield shape, with sinewy dreads flowing from its top, framed by delicately cutout triangles. A gold pectoral ring covers his chest and shoulders, and a heart is protruding toward the viewer like a pop-up, forming an open window-like portal at his chest.

Anthony Suber, “Willie and Shirley’s Son,” installation view. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Anthony Suber.

Lavender and sandalwood scents drift over from another portion of the gallery. Finding the source, one realizes that a memorial is taking place. There is an altar, a wooden chest topped with two masks adorned with metal and futuristic lights. Surrounding the masks are various objects used to memorialize: candlestick holders, incense, a jar of bells, a jar of earth, sunflowers, a spool of gold thread, and two large crow feathers. Two cushions are placed at either end of the chest, along with a folded quilt with geometric patterns and an open trunk at the other two sides. The trunk contains two mannequin hands painted white, two light bulbs, paintbrushes, and other small objects that pay homage to the act of creating. Suber’s father, who passed away earlier this year, was an artist as well. The show’s title shares his name: Willy and Shirley’s Son.

For Suber, the patterns found in his work are a part of the fabric of the history of humanity, as manifest in objects like quilts. The entire exhibition is a quilt. Among the African diaspora, these objects are passed through generations, with each generation adding to and repairing the quilt with materials and patterns found in their households. These are lived-in, holy objects, akin to reliquaries; they speak in languages of their own, and are deconstructed and choreographed into shapes that reinforce history. They also conserve energy, both temporal and spiritual, through the repetition of markings, shapes, and objects — they are compressed into latent energy, which allows one to transcend linear notions of time. Altogether, this show is an expression of the compression of patterns and sacred geometry in our lives. It lays bare the intake and expulsion of force in our natural rhythms, our day-to-day rituals and habits, and how those deceased still live with us; how they’re reborn into new energy in this world. Suber’s show is an encapsulation of this spirituality that surrounds the spaces between all of us.

Anthony Suber: Willie and Shirley’s Son is on view at Redbud Gallery in Houston through June 28, 2022.