Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

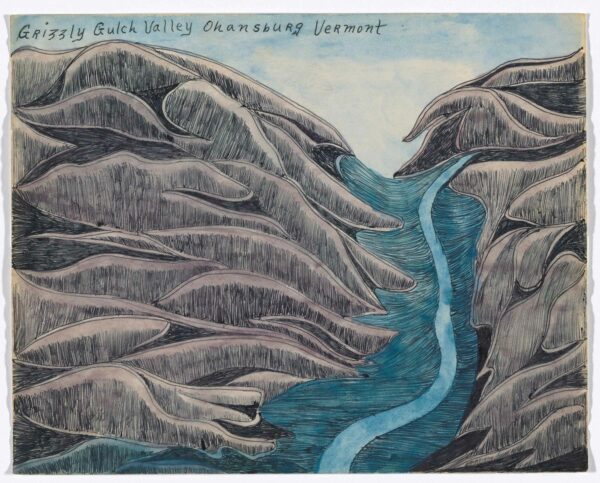

Joseph E. Yoakum, “Grizzly Gulch Valley Ohansburg Vermont,” n.d. Black ballpoint pen and watercolor on paper, 7 7/8 x 9 7/8 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Raymond K. Yoshida Living Trust and Kohler Foundation, Inc., 2013

Joseph E. Yoakum’s quixotic drawings are depictions of a world familiar yet whimsically fictitious. If you’ve not heard of Yoakum, he was a self-taught artist born twenty-six years after the Civil War. He started making fantastical drawings of locales across the globe at the advanced age of seventy-one. Ignited by a dream, Yoakum put his nose to the proverbial grindstone and created nearly two thousand drawings before his death a year later. Emerging from his desire to travel to all parts, Yoakum envisioned his drawings almost as holiday postcards with each location’s name scrawled in a wobbly handwritten text across the face of the drawings.

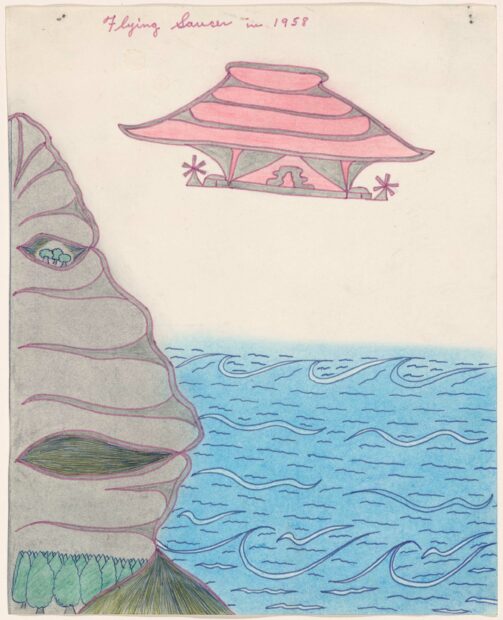

As with many artists not traditionally trained, he mostly sidesteps conventional methods of depiction for an individualized technique filled with eccentric arrangements and refreshingly direct material choices. Almost all the works are made with ballpoint pen, colored pencil, and pastel. Primarily focused on depicting the land, his art evokes the model-like masses and rock formations seen in European medieval painting. There is also a fascinating mark making and uneven perspective in nearly all the drawings. When speaking about an unschooled artist, such as Yoakum, the work is too often patronizingly dismissed as unknowing in terms of standards of western technique (as if that is the only value in art). Simultaneously, the shortage of training is frequently noted as important to the art’s childlike forthright charm — which can seem vaguely trivializing.

As those who make art understand, prowess in technique is only one door into an artwork — inventiveness, happenstance collisions, and personality of vision are other, often more powerful indicators of great art. Instead of over-valuing an artist’s technical knowledge, we should simply take the work for what it is; in Yoakum’s case, his art is invigorating in its ability to redefine how landscape can be represented.

Joseph E. Yoakum, “Flying Saucer in 1958,” n.d. Purple and blue felt tip pen, pastel, colored pencil, and blue ballpoint pen on paper, 11 7/8 × 9 5/8 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Whitney Halstead

I recommend seeing all 80 of the surprising drawings on display at the Menil Drawing Institute. While all are worth your time, I gravitated to the drawings where Yoakum is brimming with an unbridled confidence and ingenuity. In Wahoo Valley near Holdenville Oklahoma, for example, Yoakum toys with a variety of pictorial perspectives. There is a clear scale shift from larger trees in the foreground receding into smaller distant trees, accentuating a recessional rendering of space. The sky fades from a rich pinkish red into a pale blue toward the top of the page, suggesting a visually accurate sunrise or sunset. But the rendering of other parts of the land are unmoored from traditional modes of representation. They oddly flatten over the image like the peeled skin of a fruit. Etched with repeated marks, these moments of flowing land masses cohere into patterns unto themselves, while also reading as descriptions of gradations within the geography. Essentially Yoakum allows repetition to complicate our looking as we negotiate a world equally depictive and abstract. Even more unusual is the top right corner of the artwork, where a hill is inset with a vista of a lush green valley, echoing the central field of trees in the middle of the drawing. It’s like a miniature biosphere within the larger landscape, and as such feels like a secret parallel world.

Since Yoakum did not travel to all the areas he depicted, there is an overarching sense of wishful longing in the work, or perhaps an almost biblical visionary fantasy of abundance. What Yoakum’s work ultimately emphasizes through his use of amorphous surreal depictions is art as drawing of the mind. His mental projections of places around the world highlight Yoakum’s sheer inventiveness as he constructs romantic pictures born from his abundant imagination and a curious claim that they are merely “what I saw.”

What I Saw is on view at the Menil Drawing Institute, Houston from April 22 through August 7, 2022.

2 comments

Joseph Yoakum’s work is indeed extraordinary. Thanks for this thoughtful take. Note: Yoakum’s years were 1891-1972, he was born after the Civil War

Jay Wehnert

Using a very specific voice, this show is both imaginative and insistent. I liked the unique way Yoakum’s drawings described the world he imagined. Thanks for the review, Matthew Bourbon.