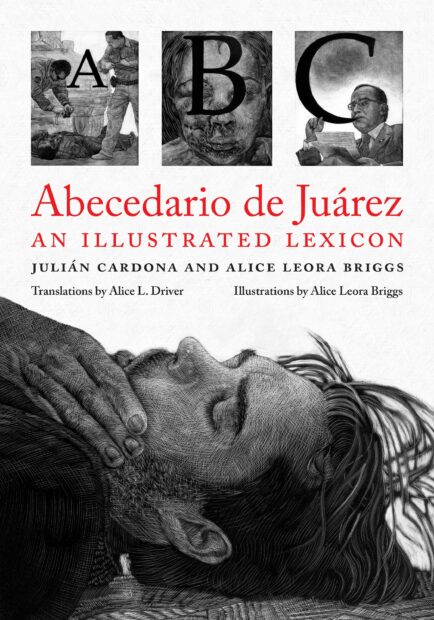

Alice Leora Briggs creates drawings, woodcuts, architectural installations, and occasional books. Ciudad Juárez has been a flash point for much of her attention and energy for fifteen years. Over 100 of her Juárez drawings are reproduced in Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon, a book written in collaboration with photojournalist Julián Cardona (University of Texas Press, 2022).

Born in an oil boomtown in the West Texas Panhandle, Briggs grew up in Idaho’s Snake River Valley. She returned to the Southwest over 30 years ago and now lives with her husband and 100-year-old mother in Tucson. Briggs is a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow.

Craig Bunch (CB): Congratulations on the publication of Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon, your collaboration with the late Julián Cardona. How did you come together on the project, and what did each of you bring to the collaboration?

Alice Leora Briggs (ALB): Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity to introduce the Abecedario to anyone who might be interested.

Charles Bowden introduced Julián and me in 2007 and in 2010 encouraged us to collapse our separate endeavors in Juárez into a single project. Julián had interviewed an evangelist who witnessed the slaughter of recovering addicts in an anexo (rehab facility), and I had completed an alphabet for Juárez, a 32-panel drawing in homage to those who had endured sexenio de la muerte (six years of death), otherwise known as the administration of Mexico’s ex-president Felipe Calderón. Initially, Julián was to write the book and I was to create drawings that would serve as illustrations. Within a year this division of labor collapsed. For the final six years of our collaboration, we met two or three times weekly on Skype to conduct research and to write. Although our online time averaged 15 to 20 hours per week, words and drawings about Juárez consumed most waking hours. I frequently went to El Paso, walked over Paso del Norte, and Julián drove us all over the city, day and night, to legal and illegal cemeteries, execution sites, the morgue, rehab centers, an evangelist’s asylum for the lost (the homeless, the mentally ill, the drug addicted). I took thousands of reference photographs for my drawings and Julián shared digital files of some of his photographs. I have no doubt that our Abecedario is a sum of errors, that it is not enough, but we gave it everything we had. I wish Julián could be here to add his perspective.

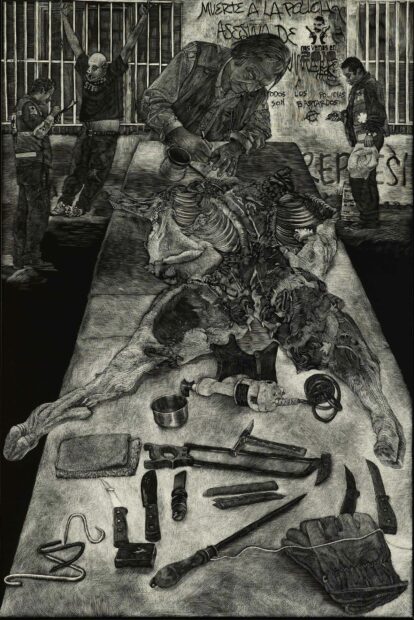

Alice Leora Briggs, “Necessary Tools,” 2010, sgraffito drawing on panel, 36 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Evoke Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM. A portrait of Charles Bowden.

CB: Beyond that important introduction, what is your debt to Charles Bowden, whose Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez (University of Texas Press, 2010) you illustrated?

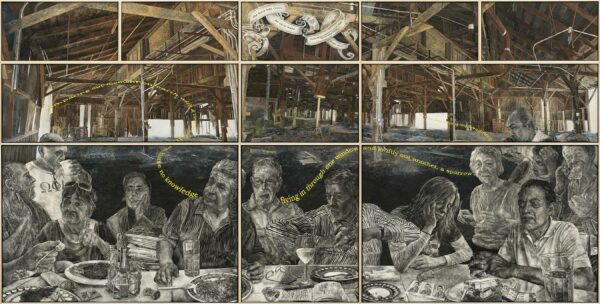

ALB: A few days after Charles Bowden died, on August 30, 2014, I passed an abandoned sawmill in Alamogordo, NM. I had wanted to explore its interior for over a year, so I turned around, parked some distance away, and slipped through a perimeter fence strung with multiple warning signs: DANGER. CONDEMNED. DO NOT ENTER. Chuck probably gave me more than I will ever know, but when barn owls exploded from the roof beams as I stepped into the mill, I realized all over again how much he had encouraged my audacity. Before I knew Chuck, I was better behaved.

Alice Leora Briggs, “La última cena/The Last Supper,” 2017, sgraffito with tinted gesso on panel, 6.5 x12.5 feet. Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM. The environment depicted in this work is an abandoned saw mill in Alamogordo, NM. Photo by James Hart.

CB: Why does Abecedario de Juárez take the form of a glossary of mostly Spanish words, interspersed with narratives?

ALB: Julián and I were initially on different trajectories. What’s interesting about this book is the manner in which our strategies became intertwined. At the suggestion of my husband Peter, I began to consider my polyptych of the Spanish alphabet as a launch pad for a lexicon that was rising out of Juárez, words invented and adjusted by citizens, the media and even government officials, to describe the violence that blanketed the city. Meanwhile, Julián was taping interviews with victims and perpetrators of crimes and retelling their stories. He also interviewed witnesses to crimes and the relatives and friends of murder victims whose vocabularies were peppered with many of the slang terms in our book.

For years, we had no clear idea of the shape of this book. There was always another slang term to be recorded and defined, another story to be told and documented. At times we considered our book to be two books, sometimes three, sometimes a series of journal articles. We juggled 27 narratives and countless slang terms, but eventually chose 12 narratives and a selection of slang for publication.

Casey Kittrell, University of Texas Press editor, suggested an expanded glossary format for our book and mentioned that Home Ground: A Guide to the American Landscape might serve as a roadmap. Edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney, this illustrated glossary of descriptive terms about the American landscape combines geography, literature, and folklore. Through Casey’s guidance, the Abecedario became a minefield, an unhinged glossary of alphabetically ordered definitions of slang terms that periodically erupt into first-hand accounts of life or death, or both. These seemingly random explosions of narrative recall the unpredictable violence during the heaviest deployment of federal forces and criminal organizations in Juárez.

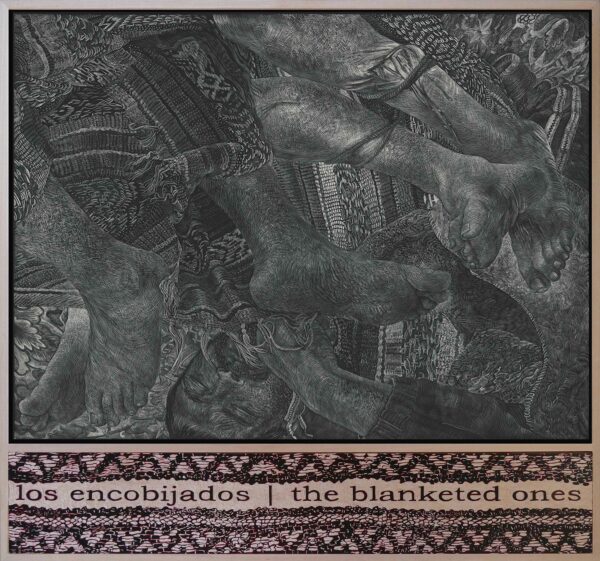

Alice Leora Briggs, “Los encobijados,” 2019, sgraffito drawing on panel, tinted gesso, carved birch, 24 x 25 inches, collection of Edward Schiller. The Spanish word “cobija” means blanket in English. Los encobijados are murder victims who have been rolled in blankets, ostensibly to avoid soiling official cars, then dumped in the desert outskirts of Juárez or in public places within the city.

CB: What is your debt to Hans Holbein’s Alphabet of Death?

ALB: Hans Holbein the Younger created several extraordinary sequences of woodblock prints in the 1500s. His Dance of Death and Dance of Death Alphabet, cut by Hans Lützelburger, revived a medieval theme that may have first appeared in a danse macabre mural at Holy Innocents Cemetery in Paris in 1424-5. Holbein’s wood engravings inspired my polyptych drawing Abecedario de Juárez, and later a suite of twelve woodcuts in homage to Mark Strand’s poem “The Room.” My work as a whole is a requiem. I find solace and inspiration in works by Holbein and other artists who grapple with death.

CB: Please describe the sgraffito drawing technique that you use so powerfully throughout the book.

ALB: “Sgraffito” fixes on two facets of my work, drawing and writing. The word comes from the Italian graffiare — to scratch. This in turn is derived from Ancient Greek, γράφειν, to cut into, to write.

I work on panels that are coated with kaolin clay and acrylic medium (for binder), then over sprayed with India ink. I pull out an airbrush loaded with India ink when areas of a drawing require a darker atmosphere or obliteration. My drawing tools are simple: x-acto knives, fiberglass pencils, steel wool, engraving tools, anything that will abrade the ink’s surface or cut into the white clay. For whatever reason, I like to cut things. It’s a bonus that each cut serves as a light in a dark field.

Sgraffito has a long history of use in wall decoration and ceramics of Persia and Ancient Greece. In 19th century Great Britain and France, paper-backed sgraffito drawings on scraperboard, or scratchboard, were developed in tandem with photo-based printing and replaced more costly methods of reproduction such as woodcut, linocut, and wood or metal engraving. I stopped making my own panels years ago. I have been cutting into expertly crafted, often custom-made panels made by Ampersand Art Supply in Buda, TX, for a few decades.

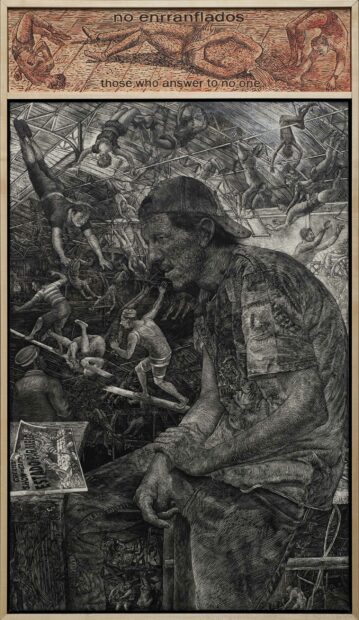

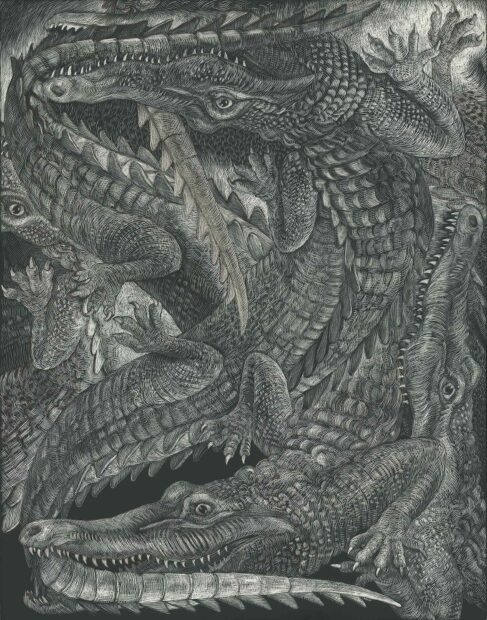

Alice Leora Briggs, “No enrranflados/Those Who Answer to No One,” 2019, sgraffito drawing on panel, tinted gesso, carved birch, 45 x 25 inches. Courtesy of Evoke Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM. “Ranfla” is used to describe a smooth ride, a car, sometimes a “low rider.” No enrranflados are those who have no “ride”; those who are not members of a gang or “family”; individuals who do not work for or report to the police or military; those who operate without the protection that affiliation provides.

CB: Let’s talk about some of the illustrations. The illustration for “W” is among the most gruesome in a book full of dark images. Why did you depict a dismembered female body to represent a letter for which there is only one glossary entry (wato)?

ALB: My approach to the term “illustration” is to ignore it until a book is assembled. For fifteen years I have made images in response to events in Juárez. Their function as illustrations almost always comes later. My Juárez alphabet marks the territory as a whole. It is coincidental if individual letters appear to illustrate specific terms. In Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon, correlations between images and words are closer at times, since I was writing and endlessly editing the text.

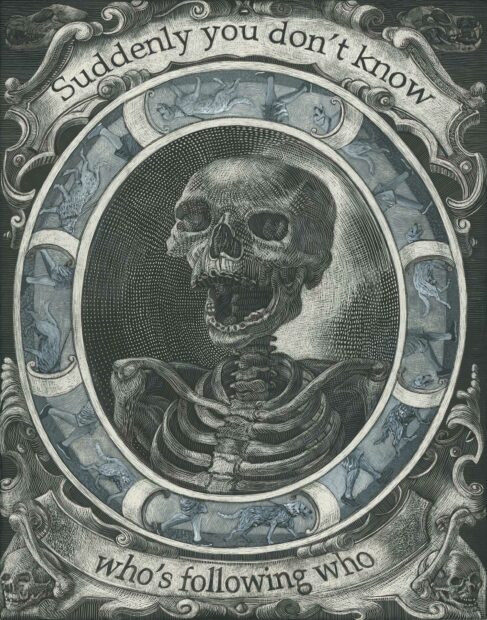

Alice Leora Briggs, “Who’s Following Who,” 2019, sgraffito drawing on panel with tinted gesso, 14 x 11 inches. Private collection.

CB: The illustration on page 77 is one of several that accompany a narrative based on Cardona’s 2015 interviews with Luis Javier Martínez, following the entry for estado paralelo (literally, “parallel state”). A portrait bust of a skeleton is surrounded by the text “Suddenly you don’t know who’s following who” and other pertinent details. Would you discuss your choice of imagery and symbolism here?

ALB: There’s not much to say except that death is either laughing or roaring in our general direction. This drawing is a rare case, as the low-tech animation in vignettes that circle the skull directly refer to a passage in the book.

Luis Javier Martínez, the owner of a chain of auto parts stores, was nearly extorted out of existence. He reflected on his understanding of relations among criminals, municipal police, and civilians like himself: Suddenly you don’t know who is following who. Is the owner walking the dog or is the dog walking the owner?

CB: The illustration on page 99 seems to refer to the glossary entry for House of Death, “a mass grave discovered in 2004 beneath a patio at 2633 Los Parsioneros in Las Acequias, a middle-class Juárez neighborhood.” (The address in the illustration reads “3633.”) I’m struck especially by the highlighted foreground which features a flayed body that might have emerged from a Renaissance anatomical print. Tell me more about this.

ALB: Thanks for pointing out this typo in the text! The correct address, 3633 Parsioneros, is cut into the drawing.

I often populate my drawings with fragments of images from other centuries and cultures, as human frailty has no respect for time or place. During the administration of Felipe Calderón, Juárez was a flashpoint for human depravity, but it did not have a corner on the market.

Alice Leora Briggs, “Death of the Suitor,” 2007, sgraffito drawing on panel, 60 x 40 inches. Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM. Photo by Rudy Torres.

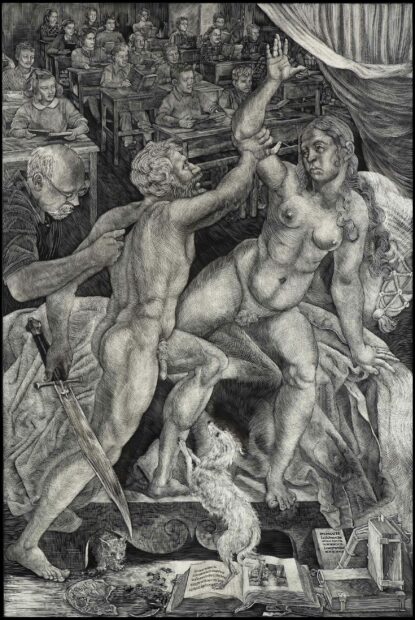

CB: Your illustration on page 197 appears to have been modeled partly on Lucretia en Sextus Tarquinius by Heinrich Aldegrever, after Georg Pencz, dated 1539. I am not sure what the many surrounding details you have added refer to or if the illustration refers to a particular glossary entry. The image is dated 2007 and a large detail appears in Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez. Please enlighten me.

ALB: The rape of a woman named Lucretia quite possibly triggered a Roman revolution. The rapes, tortures and murders of women in Juárez are amplified and multiplied in rumor mills that churn around the world. Maybe it is a biological imperative to feel greater horror for the women. Ninety percent of Juárez homicides during the Calderón administration were men. Culpable or not, the men were often presumed guilty.

Books serve as a means to speak with a wider audience. They include reproductions of my drawings that convey some of the qualities of the singular works, but can’t possibly serve as their equivalents. For example, the “Lucretia” image mentioned above is a reproduction of my drawing, Death of the Suitor, that measures 60 by 40 inches.

I am not fastened to narratives. I sometimes digitally rearranged drawings or extract details to serve as illustrations in the book. I have been fortunate to work with talented people and enjoy giving them room to add their visions. In this case, designer Cassandra Cisneros moved Death of the Suitor from its original proximity to the term trata de personas (human trafficking) to face tierra arrasada (scorched earth), or state-sponsored aggression that targets whoever and whatever stands in the way of the state. Cisneros’s thoughtful placement now suggests that an entire generation is being schooled to accept terrorism as the natural order.

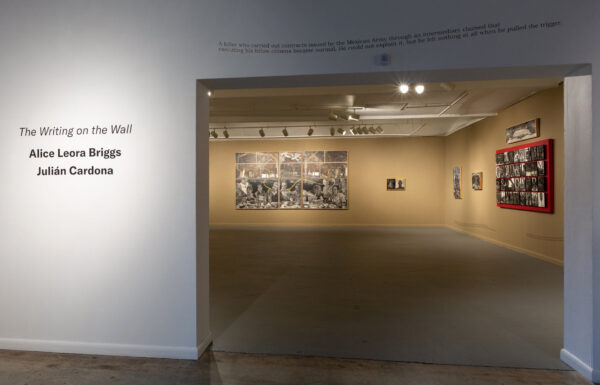

CB: I was blown away by The Writing on the Wall, your show in 2020 at Art League Houston. You and Julián Cardona received equal billing, despite the art (I assume) being entirely your creation. Part of what made the exhibition so powerful was the large scale of many works — something that is lost in translation to book form. (Even with a magnifying glass I couldn’t read all of the text at the bottom of your Lucretia illustration on page 197.) What are your thoughts on scale?

ALB: I’m honored that you found the Art League Houston show interesting, or I hope that might be what you are saying? Yes, I created all of the drawings in the exhibition. The serpentine phrases that traversed the walls were words that I modified from interviews that Julián conducted with fellow Juarenses. This exhibition was an acknowledgement of our decade-long conversation about Juárez. Though not a two-person show in the conventional sense, much of this work would not have been possible without the unusual partnership that Julián and I shared. I make work that ranges from six square inches to whatever I can get away with. Some ideas are best viewed from the distance that a magnifying glass requires, and others swallow the audience. I make pictures and I make structures that my father once called “ransacked tombs.” The largest of these has measured over 6,000 cubic feet. I have plans to build Asilo (asylum, shelter, refuge) in Dallas at Kirk Hopper Fine Art at the end of this year.

Alice Leora Briggs, “Dar cuello, To Give [it to them in the] Neck,” 2020, sgraffito on panel, 14 x 11 inches. Courtesy of Evoke Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM.

ALB: What I now know of Juárez is not first-hand, but arrives in various newsfeeds. Though I have just finished co-writing a book about Juárez, this is largely based on research conducted between 2010 and 2019. My feet have been nailed to a floor on this side of the border for a few years due to the pandemic and the care that my 100-year-old, live-in mom requires.

No, I am not hopeful for the future. There are continuous battles to control enormous income streams that criminal enterprises (including those within the government) generate in Mexico. The locus of violence shifts from one region of the country to the next. Total impunity, or something close to it, is the rule of law.

Numerous clandestine crematoriums have been uncovered. In a February 28, 2022 AP News article, María Verza writes about one of these ‘extermination sites’ where the tortured and murdered were burned:

How many disappeared in this cartel ‘extermination site’ on the

outskirts of Nuevo Laredo, miles from the U.S. border? After six

months of work, forensic technicians still don’t dare offer an

estimate. In a single room, the compacted, burnt human remains

and debris were nearly 2 feet deep.

In a January 7, 2022 Washington Post article, Maite Fernández Simon relays a report by La Jornada Zacatecas that the bodies of eight men and two women were found in a parked van near the governor’s office in Zacatecas City in north-central Mexico. Zacatecas, one of the most violent states in Mexico, registered a 52.2 percent increase in murders from January to November 2021, compared with the same period in 2020.

Then there are murders of Mexican journalists: Roberto Toledo was killed on January 31, 2022. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, an independent nonprofit that promotes worldwide press freedom, Toledo was “the fourth media worker killed in Mexico in less than a month. On January 10, José Luis Gamboa was stabbed to death in Veracruz and two other journalists, photographer Margarito Martínez and broadcast reporter and news anchor Lourdes Maldonado, were shot dead in Tijuana on January 17 and January 23 respectively.”

Regarding hope in general… The other day Eric Avery walked into my studio and pulled from a box a small handmade canary cage, probably fashioned by a miner in the previous century. As we admired the workmanship, we joked that the sound of screaming canaries is now deafening. And this is no joke.

****

Craig Bunch is a native Houstonian who has called San Antonio home since 2011. His book The Art of Found Objects: Interviews with Texas Artists was published by Texas A&M University Press in 2016. Dreams, Visions, Other Worlds: Interviews with Texas Artists (forthcoming from the same press) features an earlier interview with Alice Leora Briggs, as well as 59 other interviews. He is co-curator, with Kris Larson and Mari Omori, of Affinity for Collage at Lone Star College Kingwood, on view from March 21 through April 22, 2022.

2 comments

This is a wonderful interview with Alice Leora Briggs, whose deeply compassionate works take us to some dark places. She constantly challenges us to see a world that we at times prefer not to see. Alice’s work is beautiful in its honesty

and profoundly moving.

Thank you so much, Mike Brimberry for your generous remark. And much gratitude to Craig Bunch for creating this opportunity and to Leslie Moody Castro for the attention and care that she devotes to Glasstire’s content.