Erin Segal, publisher at Thick Press, recently talked with artist Mark Menjivar about social practice (aka socially engaged art) and anti-death penalty activism. Thick Press and Menjivar are collaborating with Rickey Cummings, who has been on death row in Texas since 2012, on a booklet entitled “Holding Vigil.” Learn more about Cummings’ case and how you can help at iamrickeycummings.com.

Erin Segal (ES): As a socially engaged artist and publisher, you’ve produced installations and publications related to capital punishment. I’d love to hear more about this body of work and how it came about.

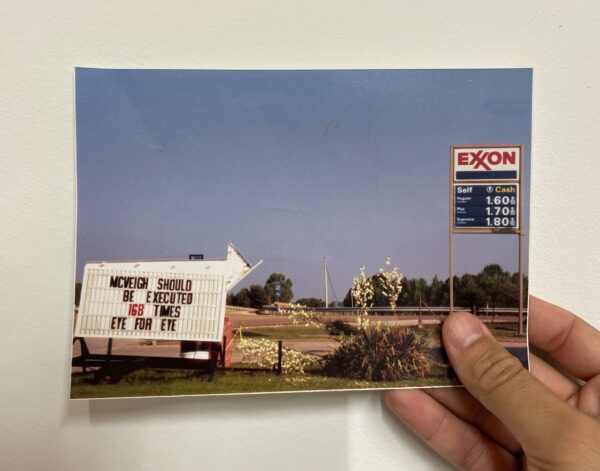

Mark Menjivar (MM): I first started thinking about state-sanctioned violence when I was studying social work in college. A professor gave me this picture about Timothy McVeigh being killed 168 times — speaking to an “eye for an eye” ideology.

I’ve kept that with me – it’s actually one of the few things I have from that period of my life – and it always made me reflect on using violence for retribution. I’m not a pacifist (I tried to be), but the use of violence, particularly by the state, for punishment, has always been hard for me.

I started to become really haunted by capital punishment in 2013 when Texas executed its 500th person since 1976. Prior to that I had some interactions with vigilante justice in Bolivia that led me deep into lynching culture, but that number 500, just really haunted me. And it made me start to ask questions about the system, about how to explain violence to my small children, and about trauma.

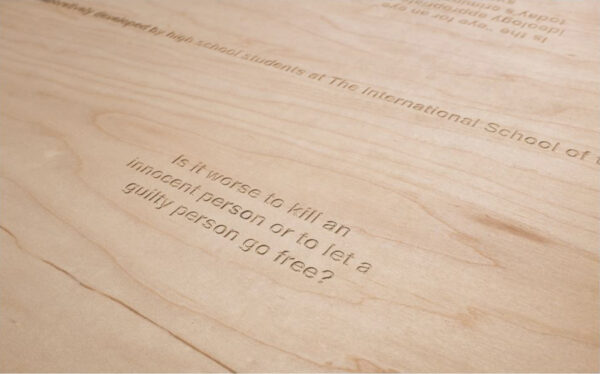

Over the years I’ve learned that when I start to ask questions it’s best to not ask them alone. Collectively, we can ask better questions, and arrive at better answers. And I particularly like asking questions with young adults because they tend to have different ways of viewing issues than I do. Brighter. Crisper. So when I started asking questions about capital punishment, I reached out to my friend Ryan Sprott who was teaching world history at a public high school in San Antonio. I asked if he had any students who may want to spend a year looking at capital punishment from diverse perspectives. We developed a project structure, really a class, and put out an invite to students. Over 30 signed up, and we spent the year working directly with families affected by capital punishment, and with documents from Texas’ state archives. We made zines, drew directly onto court documents, and made a participatory picnic table that had six questions carved into the table top as the centerpiece of a final exhibition. After the exhibition closed, the table went back into their high school and the students used it the next school year to engage their peers and visitors in dialogue.

Students sitting at the participatory picnic table they created to engage the public in dialogue around capital punishment.

When I started working with the youth, I felt like I didn’t know much about capital punishment. A few months in I found myself thinking, “Ah, okay. Now I get it.” But then I very quickly found myself back at a place of feeling confused. Capital punishment is super complex. It’s not just about an execution. It’s about poverty and race. It’s about class and education. It’s about religion and revenge and forgiveness. It’s about mental health and broken homes.

ES: So much.

MM: Yes, so much is below the surface of a death sentence.

While working on that project with the high schoolers, I met folks at the Texas After Violence Project (TAVP) based in Austin, Texas. They are a community-based archive and documentary project cultivating deeper understandings of the impacts of state-sanctioned violence on individuals, families, and communities. We really worked well together and decided to keep trying to collaborate.

While visiting their offices one day, I learned that they had a number of archives related to capital punishment that had yet to be made public. One of them was the Execution Files, which were the research files for a book called The Rope, the Chair, & the Needle that was written by Dr. James Marquart and two others in the 90s. The archive had a folder for every person who was executed from 1923 until 1988, and included images, documents, and other relevant information. It is a haunting and complicated archive that we are still working on today.

I just recently completed an in-depth oral history with Dr. Marquart, talking about the complicated history of how the archive came to be. TAVP staff and I are also working to identify descendants of those who have been executed and are represented in the archive. We want to invite them to be involved in determining how to best care for the archive.

Another archive they had was the full contents of the cell of a man named David Lee Powell, who was executed in 2010 after spending 32 years on death row. He left his belongings to a filmmaker and friend named Sally Norvell so she could work on a project with them. She had his things for a couple of years, but then donated them to TAVP with the hopes that they would be made public. I have been making projects from David’s possessions for the past few years in different contexts. These include a couple of books, a musical score, and various gallery installations.

After working with these archives for a number of years, I started to think about what those who had been executed would say if they were still with us. And I remembered that we have almost 200 people currently sitting on death row in Texas. So I started a new project a few years ago called Open Letters, which invites people currently on death row to write letters to the public about the trauma that they and their families have faced post-conviction. These letters are then read publicly and I facilitate a response to them. The events are recorded and the transcripts are returned back to the authors on death row. The project debuted at the Rothko Chapel in Houston in 2018 and is now a book.

ES: In Open Letters, you mention an activist who has been to every execution since 1982. I know there are also professional advocates (like lawyers and nonprofit staff) involved in efforts to defend individuals and change policy. And filmmakers, artists, writers, etc. Can you describe the death penalty activism landscape that you’ve encountered? What does it look like and where do you situate yourself?

MM: Those involved in work against the death penalty vary widely in form and conviction. Some people approach it from a religious perspective and hold weekly vigils to pray. Some people protest with signs and words. Some people work on the legislative end, trying to target state governments. Some people provide direct legal representation for individuals on death row. And some do all the above and more. There are some incredible people who have been laboring for a very long time.

The woman you are talking about is named Gloria Rubac, and she has been a death penalty advocate for decades. She has been in Huntsville, TX — where executions take place — for every execution since 1982. She really is one of my heroes. Her dedication, presence, and voice continue to remind people of the injustices happening. I first saw her in Huntsville when I attended the execution of my friend Christopher Young. Chris I had been writing together for 2 years when he got his execution date. Gloria was there with a bullhorn talking about Chris’ life and keeping the small crowd that had gathered up to date on final decisions coming out of the Governor’s office.

The last time I saw Gloria, I was visiting Rickey Cummings on death row. There I was, sitting and waiting, and Gloria walked in the room. I was surprised and not surprised at the same time. She seems to be everywhere.

I often find myself functioning in between advocacy groups, the general public, and the art public. I am often trying to get people thinking about capital punishment who may not have ever thought about it before. And I am often partnering with advocacy groups like TAVP or the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. During exhibitions and at events, people will often ask, “What do we do now?”, and I try to connect people with these community organizations. And I encourage people to start talking about it with their friends and their family. I am deeply motivated to try and get people who have never really thought about capital punishment to begin considering it.

ES: It seems to me that your work is political, but it’s not propaganda. You are exploring, and asking others to explore, too. Is this correct?

MM: I really am. I often think about the word invitation. I find myself being deeply curious or troubled by an issue or event and try to learn more. And not just facts about an event or an issue, but the emotional work, too. And I try to invite people to do that with me.

I have often said that I value dialogue over debate in my art practice. I see debate as being about trying to convince another person that I’m right and they are wrong. And dialogue begins with listening. I think there is definitely a place for debate – and it’s needed. But I try to start with a posture of listening with these issues.

I am most often trying to keep one foot in and one foot out of various contexts. So in thinking about art and activism, I try to do the same thing. Art often gives you very little instruction of what to do when it comes to social issues. It can often be more about awareness. And often activism is trying to tell you exactly what to do. I like to try and function a bit between those spaces.

ES: Why are so many artists, filmmakers, and writers attracted to making work related to the death penalty? Do you ever worry about ethical issues?

MM: I think people are drawn to death penalty work because it is so intense and complicated. As I mentioned before, a death sentence is never just about one thing. It has so many layers and most of them exist below the visible surface. Violence in our communities, including capital punishment, affects so many people. It hurts not only the people directly involved, but those around them. Their friends, their family, their neighbors – even people who just hear about it.

I think about ethics all the time. Early on in this work, I felt that maybe I could only work on death penalty issues if I had been directly affected by the system. But I quickly came to my role as citizen and taxpayer in the system and felt firmly grounded. And now I find myself working and advocating from a place of deep relationship with those being affected.

One thing that has really helped me in considering ethics is to work as openly and transparently as I can. Always coming back to collaborators. Always being open and willing to change. I have also learned to not make assumptions and to value working slowly. This allows things to change and adapt as needed.

ES: I hate to use the word “evaluate” because Julie and I try to avoid thinking of care work – and art, too – in instrumental terms. I guess I’m just wondering how you know if the work is worthwhile, how you know if the work is working.

MM: I sometimes think about the work I’m doing in terms of effectiveness, but not always. I am trying to create work that has multiple entry points and hopefully, multiple exit points. What I mean by that is that I want people from a broad spectrum to be able to have a meaningful encounter with the work. And this can be a museum curator, a journalist, or my grandmother – who comes with very little to no contemporary art historical context. I hope that each of them can find a way into the work that brushes up against their own experience.

I often think about providing “handles” for people in this work as well. The content they are encountering can be difficult – and it should be. We are talking about state sanctioned violence. And that can shake us, but I don’t want people to fall down. So the handles will hopefully give them something to grasp for, to hold onto. And those handles can look like different things. They can be objects, actions, ideas, or even values like love and hope.

And when I talk about multiple exit points, I mean that each person can walk away from the work with something. For some, that will be getting involved in direct advocacy or having a new sense of urgency for the work they are already doing. For others, it may be the first time they are thinking about state sanctioned violence, so the work is just a seed and you never know when it will sprout and give sustenance or beauty. And a large part of making the work effective is by making the work in collaboration with or alongside people who I deeply respect and those who have been deeply involved in the movement for years. The trusted individuals, and participants in the projects, can provide critical feedback along the way. And with much of this work you never know if and when it resonates or blooms. So I guess in a way, all I’m really trying to do is produce good seed.

ES: We land on that idea so often in our conversations with people involved in the work of care and justice: we can’t ever anticipate the outcome of our work, so we should just focus on the work itself, and in particular, on the relationships.

MM: So true, Erin. Great words to end with.

* 6 Questions Remain

—What are the social, moral and political implications of an execution?

—Is the “eye for an eye” ideology appropriate for today’s criminal justice system?

—The average death penalty case on Texas costs taxpayers about $2.3 million, three times the cost of imprisoning someone in a single cell at the highest security level for 40 years. How do you feel about this? How could these funds be used more effectively?

—The average stay on death row is close to 15 years. During this time, prisoners are sharply restricted in terms of visitation and exercise, spending as much as 23 hours a day alone in their cells. Is this cruel and unusual punishment? Is this too lenient?—Is it worse to kill an innocent person or to let a guilty person go free?

—How would you feel if a loved one was a victim of a crime that resulted in the defendant being placed on death row? How would you feel if a loved one was the defendant in death row?

Learn more about Menjivar’s Open Letters project here and here. Glasstire is the online publishing partner for Menjivar’s new publication with Thick Press. Learn more about that here.